Background information

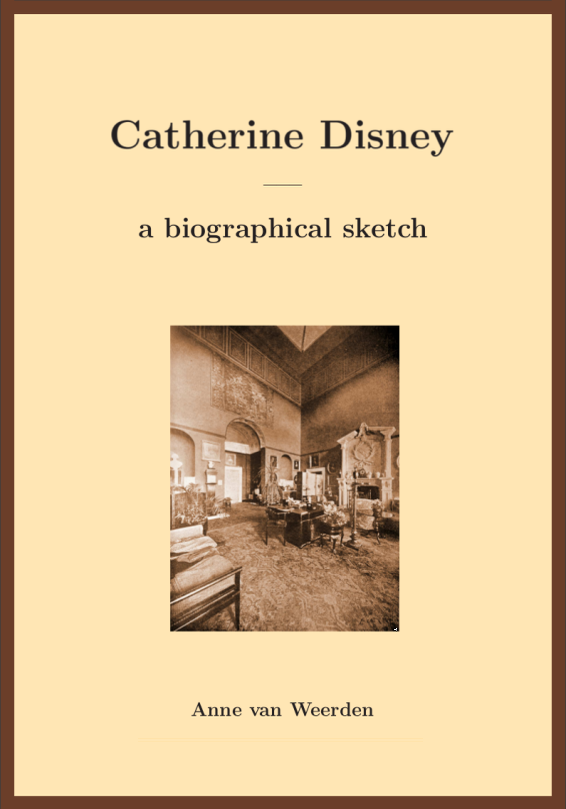

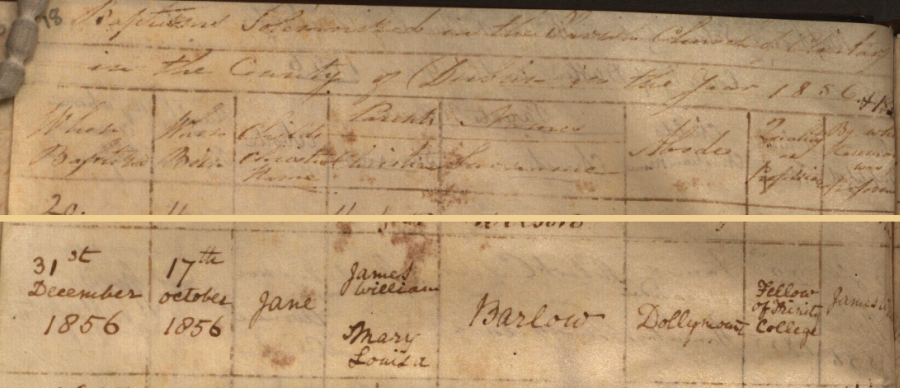

Utrecht, 4 November 2024 — Catherine Disney and William Hamilton at Killester station

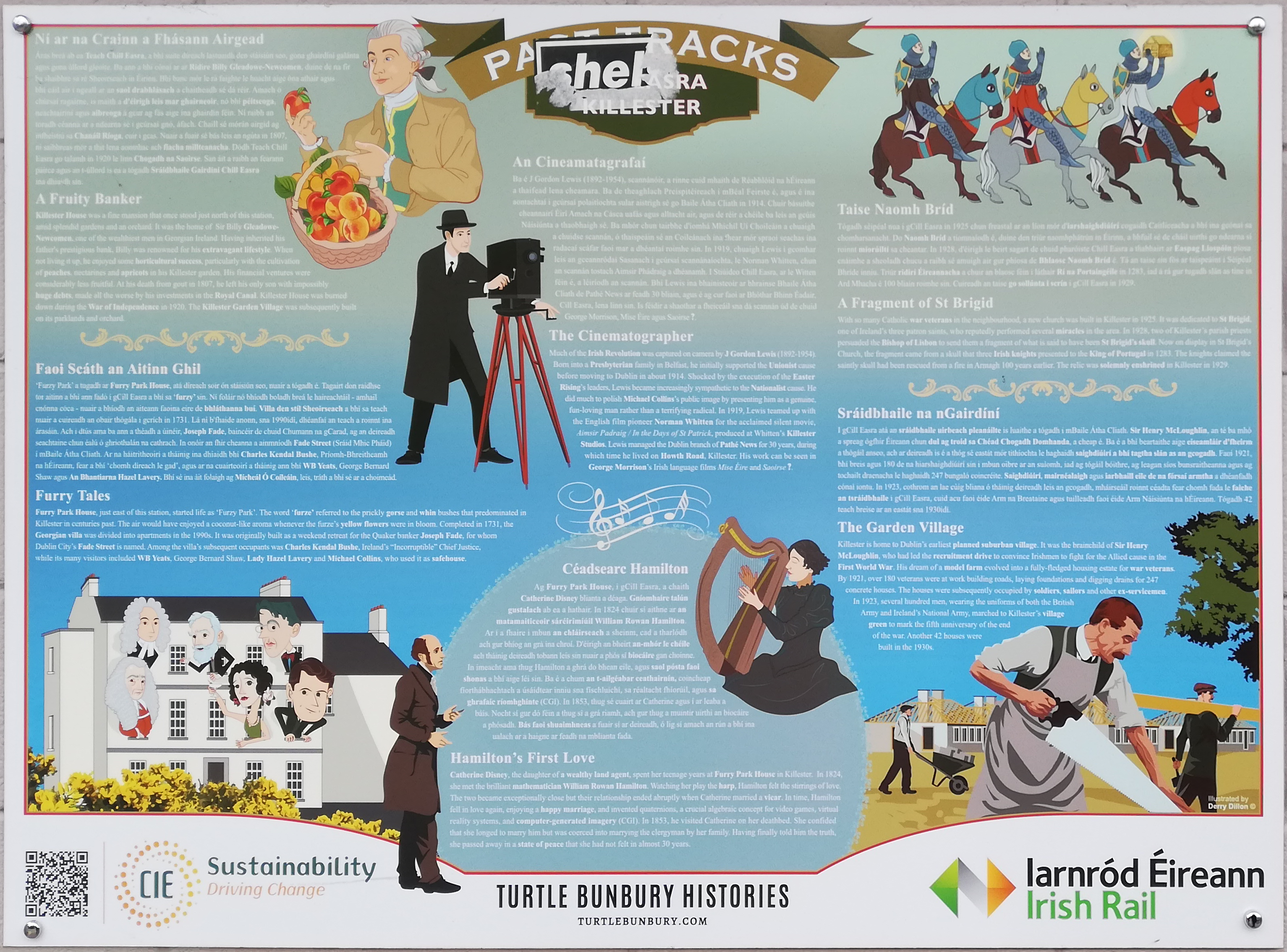

In early May this year I was contacted by the historian Turtle Bunbury, with whom I had been in contact since 2019. Every now and then we corresponded about Catherine Disney and her family, within his larger context of the Brabazon family. Turtle wrote that he was “involved in a project creating local history stories for train stations around Ireland.” He was working on a panel for Killester station in Dublin, about Hamilton and Catherine Disney, because during her teens Catherine had lived in Furry Park House in Killester. I was happy to be allowed some comments, and in April Turtle sent me an image of the “relevant section” of the panel, showing the short story of Hamilton and Catherine Disney. It was amazing, and very accurate.

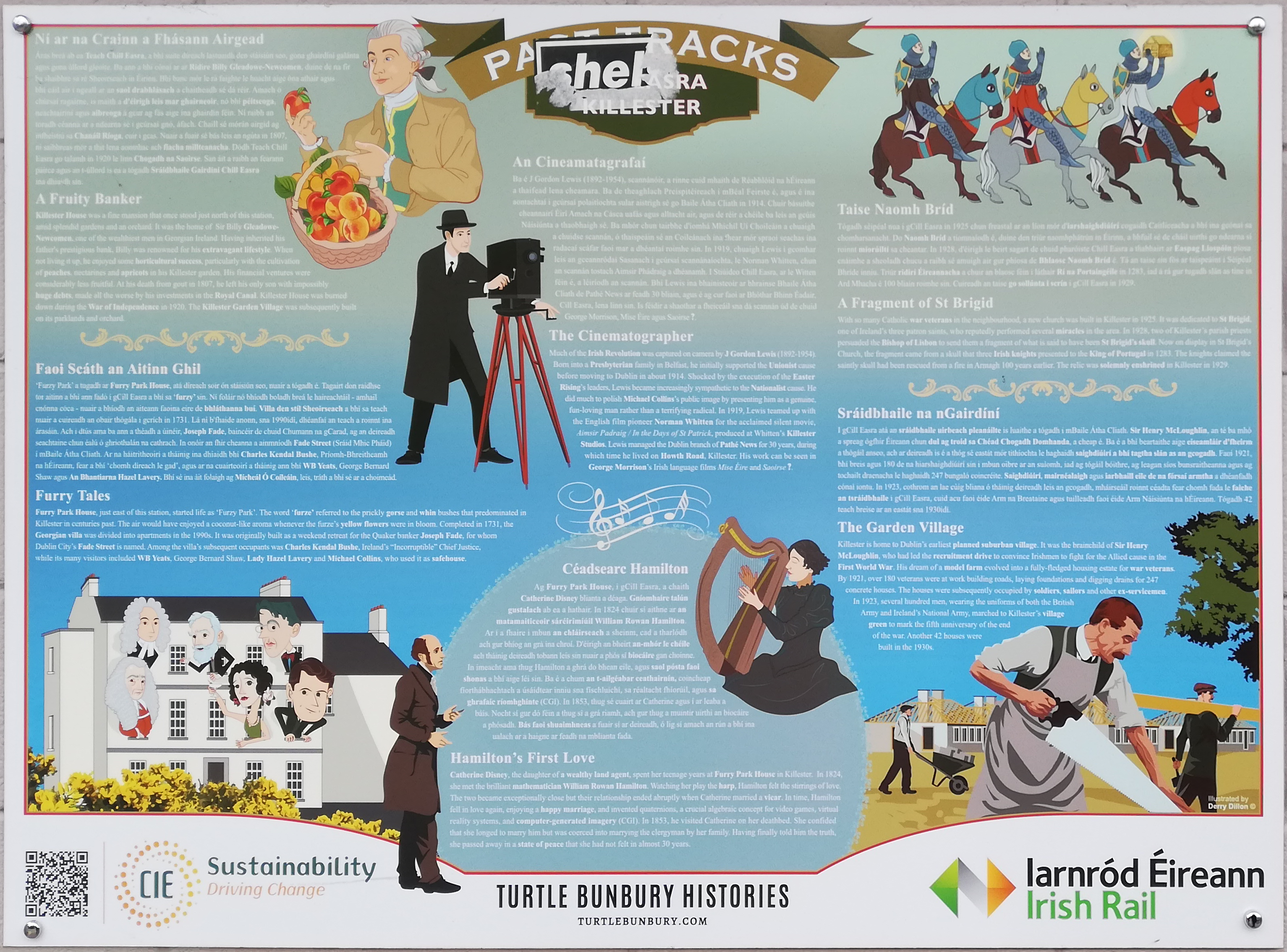

Having arrived in Dublin on the 12th of October, in order to attend the unveiling of the plaque for Hamilton on the 16th, in the meantime we wanted to photograph some for me missing pages of the indexes of Hamilton correspondences at Trinity College Library, and hoped to find some more information about Lady Hamilton’s last years in ‘Bloomfield retreat’. One of the things we did on the 13th was go to Killester station by train, to see if Turtle’s panel was already hung up at the station.

Arriving at the small station we walked around, searching for the panel, becoming a bit disappointed because we did not see it. Assuming the project was not yet in the public stage, we decided to leave the station in order to make some photos of Furry Park House, and suddenly, there it was, on the wall outside the station!

The panel Turtle Bunbury made for Killester station.

The panel gives the six Killester stories in Irish first, then in English. The English version of the story about Hamilton and Catherine reads,

“Hamilton’s First Love

Catherine Disney, the daughter of a wealthy land agent, spent her teenage years at Furry Park House in Killester. In 1824, she met the brilliant mathematician William Rowan Hamilton. Watching her play the harp, Hamilton felt the stirrings of love. The two became exceptionally close but their friendship ended abruptly when Catherine married a vicar. In time, Hamilton fell in love again, enjoying a happy marriage, and invented quaternions, a crucial algebraic concept for video games, virtual reality systems, and computer-generated imagery (CGI). In 1853, he visited Catherine on her deathbed. She confided that she longed to marry him but was coerced into marrying the clergyman by her family. Having finally told the truth, she passed away in a state of peace that she had not felt in almost 30 years.”

I was so happy with it, that I decided to mention it in my short speech at the unveiling of Hamilton’s plaque on the 16th.

Yet because I always have to act if I see something to comment on; as the only detail, it is a bit unfortunate that Hamilton’s quaternions were mentioned, but not his mechanics. This problem was mentioned more often while we were in Dublin, and was indeed noticed already in 1866, when it was written about Hamilton’s work, “It is as yet premature to anticipate on which of his investigations or discoveries Hamilton’s fame will ultimately rest. There are mathematicians among us who in this respect would be inclined to name his Calculus of Quaternions; others would say that none of his writings can overshadow the importance of his Dynamical Theorems.” It will always remain difficult to see Hamilton’s work in its entirety.

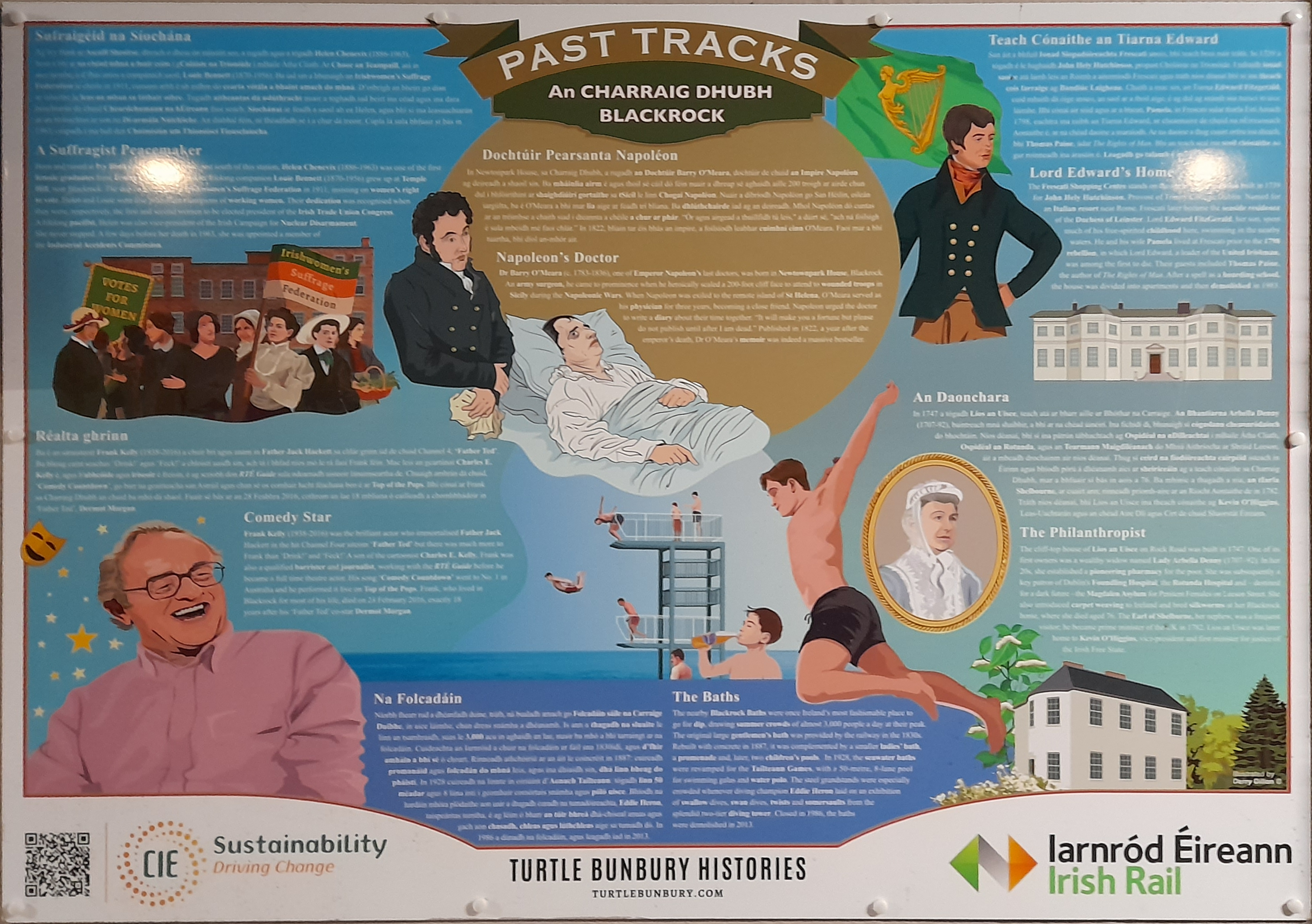

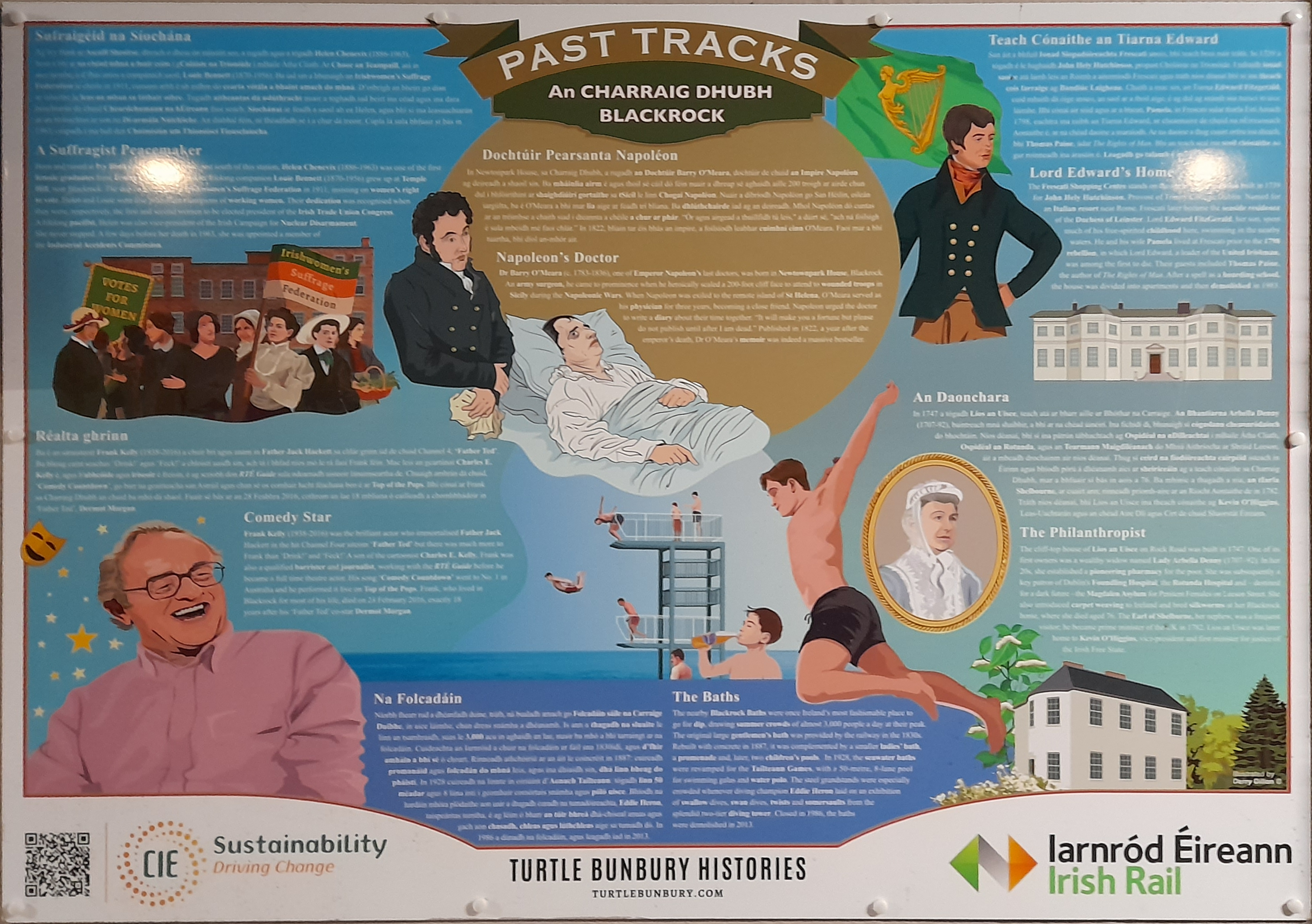

A surprise at Blackrock

Because the storm Ashley hit on Sunday 20 October, we could not leave Ireland: the planned ferry crossing of the Irish Sea, from Larne to Stranraer, was

cancelled. Having booked everything anew (trains, ferries, and hotels), we suddenly had a day left.

In the stormy evening we took the train to Blackrock, to see the sea, and because after the death of her husband in January 1849, Hamilton’s good friend Lady Pamela Campbell (1795-1869) went to live with her daughters at Frescati House, or “Frascati, Blackrock,” as Hamilton’s biographer Graves called it. Most likely in 1851, Hamilton and his wife Helen Bayly visited her there; it was one of the very few visits of which it is known that Lady Hamilton accompanied her husband. She may have come with him more often of course, but this time Hamilton mentioned it to someone in a letter.

Having enjoyed the sea in the dark, the strong wind, the rising moon and Jupiter, we ate something in a restaurant, and walked in the storm for a short time. Just as we decided to return to the station, we unexpectedly saw the Frascati Mall which, as Charles Mollan had once told me, was built on the place where Frescati House once stood. Yet because we did not want to risk becoming stuck in Blackrock because of the storm, we did not search for the small plaque, commemorating Lord Edward and Frescati, which I had understood was there somewhere, allegedly difficult to see because of hedges which often grow in front of it. We returned to the station, where we had to wait for 18 minutes. And suddenly we realised we were standing before another of Turtle’s panels! Amazing. And even more surprising was that the panel was precisely about Frescati house, and the parents of Lady Campbell.

The panel Turtle Bunbury made for Blackrock station. Because the photo was made in the evening, it is just too unsharp to show readable texts.

The English version of the local story about Lord Edward FitzGerald on this panel, at Blackrock station, reads,

“Lord Edward’s Home

The Frescati Shopping Centre stands on the site of a fine mansion built in 1739 for John Hely Hutchinson, Provost of Trinity College Dublin. Named for an Italian resort near Rome, Frescati later became the seaside residence of the Duchess of Leinster. Lord Edward FitzGerald, her son, spent much of his free-spirited childhood here, swimming in the nearby waters. He and his wife Pamela lived at Frescati prior to the 1798 rebellion, in which Lord Edward, a leader of the United Irishman, was among the first to die. Their guests included Thomas Paine, the author of The Rights of Man. After a spell as a boarding school, the house was divided into apartments and then demolished in 1983.”

Not only had we thus completely coincidentally found a second panel, I also had not known that her parents, Lord Edward FitzGerald (1763-1798) and Pamela Syms (ca 1773-1831),* had lived at Frescati, which means that also Lady Campbell lived there as a child. Hamilton met Lady Campbell in Armagh, just when he had discovered for the first time that Catherine Disney was unhappy in her marriage. He had been in utter distress, Lady Campbell had consoled him, and since then they had remained to be very good friends. Now writing this blog and searching for sources it is obvious that I could have known that Lady Campbell had lived in Blackrock when she was young. Already in the 1750s her grandparents had bought Frescati, her father Lord Edward had spent much of his childhood there, and he came to live there with his wife Pamela in 1793; Lady Pamela Campbell having been born ca. 1795, she may even have been born in Frescati House. Our extra storm-day thus appeared to be full of unexpected information!

*

On the Wikipedia page of Lord Edward, it is rather carefully stated that Lady Campbell’s mother, Lady Pamela FitzGerald, may have been an illegitimate daughter of Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, and Madame de Genlis, yet the bias to believing it is clear, and no sources are given. More unfortunate is that both on the Wikipedia page of Lady Campbell, and on that of Frescati house, the unfounded suggestion is repeated, but now without hardly any warning, something which should not be done in an encyclopedia. A simple sentence like “She was believed by some to be” should be a reason for protest, even when in this case that belief already exists since in any case 1878. In his Compendium of Irish biography, Alfred Webb (1834-1908) expressed it using the words “most probably” without explicitly warning that there is no proof. This kind of repetition of unfounded suggestions, that is, without explicitly mentioning that there is no proof, is also what ruined Hamilton’s reputation; most readers take it for granted and spread such suggestions as facts.

Yet Webb also called Pamela a “ward” of Madame de Genlis, and that is in any case accurate. Coincidentally, during my still unfinished searches for Hamilton’s French family, I came across the Mémoires of Madame de Genlis, Stéphanie Félicité Ducrest de Saint-Aubin (1746-1830), an influential French novelist and playwright, and Pamela Syms’ “adoptive” mother, or indeed, her warden. In the fourth volume of her Mémoires, Madame de Genlis wrote that, when Lord Edward FitzGerald (lord Édouard) had asked her to marry Pamela, she “showed him the papers proving her birth”; Pamela was born on Fogo, Newfoundland, as a daughter of a man of “good birth” called Seymours and Mary Syms, and her name had been Nancy. But when she was eighteen months old, her father died. Her mother, being destitute, returned to England, where four years later “Mister Forth” saw her, and he brought Nancy to France, where Madame de Genlis took her on as an “apprentice” (French: pour apprentissage), and gave her the name Paméla.

This story is in no way incredible; Irish settlers came to Fogo in the 18th century, and in Spaniard’s Bay, also Newfoundland, there even is a ‘Seymours Road’. It is not suggested here that the road was named after him; it shows that it was a well-known name. Moreover, also the story itself is perfectly credible; what the Duke of Orléans had asked Mr. Forth to look for was an English girl, to accompany his twin daughters, born in 1777 and both called “Mademoiselle”; when Pamela came, apparently in 1799, they were toddlers. One of the twins died young, and writing about Lord Edward’s marriage proposal Madame de Genlis remarked, “Paméla [was a] companion throughout Mademoiselle’s childhood and early youth, and in terms of the English language, useful for her education.” If there is no clear evidence that someone is lying, the inclination should be towards believing.

For an extensive discussion of Pamela FitzGerald’s life and descent, in which it is concluded that “while no birth certificate has been located, the research presented here leans heavily towards the opinion that Pamela was of English birth,” see Laura Mather, The Life and Networks of Pamela Fitzgerald, 1773-1831.

NB. Curiously, Madame de Genlis called Pamela ‘Syms’, after her mother, but women keeping their own names after marriage was typical for France; in England she must have been called Nancy Seymours.

Utrecht, 2 November 2024 — A remarkable find in Edenderry

On 16 October, during the unveiling of the plaque for Hamilton at Dominick Street, there were spectators, even though the photos do not show them. Two of them were Rod and Glen Smith, who were in Dublin fore the presentation of Rod’s latest book, Clancarty: The high times and humble origins of a noble Irish family. Glen is related to both Catherine Disney and the Guinness family; being the great-granddaughter of Zara Guinness (abt. 1838-1883), she is the great-great-granddaughter of William Newton Guinness (1810-1894), whose daughter Harriet Ellen Guinness (1839-1931) married Brabazon John Barlow (1833-1900), Catherine Disney’s fourth son; Brabazon therefore was Glen’s great-granduncle. He was born 24 March 1833 at ‘Edenderry Glebe’, the house where Hilary Thompson now lives, see below. Quite stunning, to contemplate on that.

During the plaque ceremony I had looked for Hilary, but I had not found her, and at the same time I was not certain because I did not know what she looked like. But in the meridian room at Dunsink, after the ceremonies were over, suddenly someone addressed me, and introduced herself; Hilary had come to Dunsink Observatory.

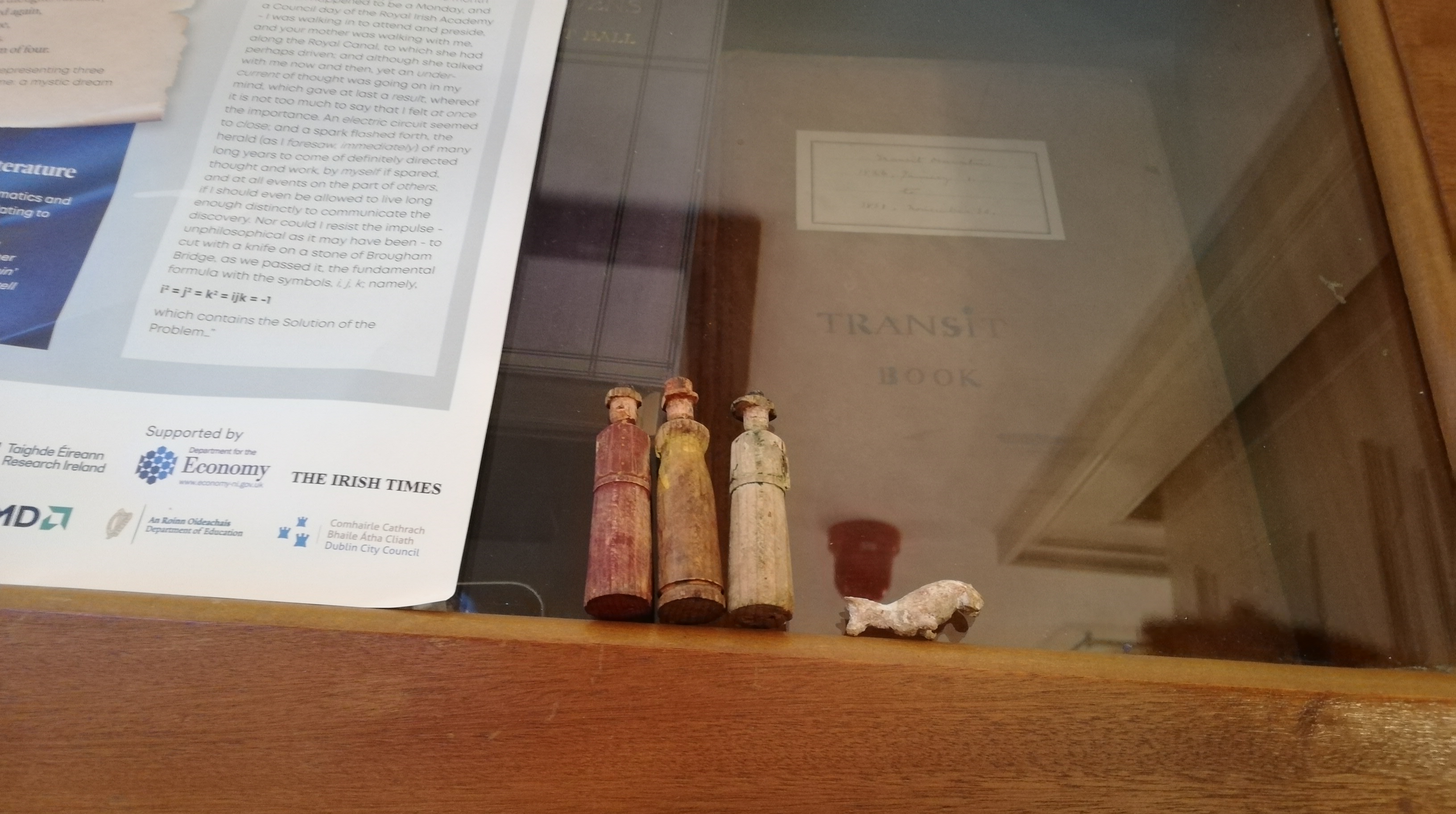

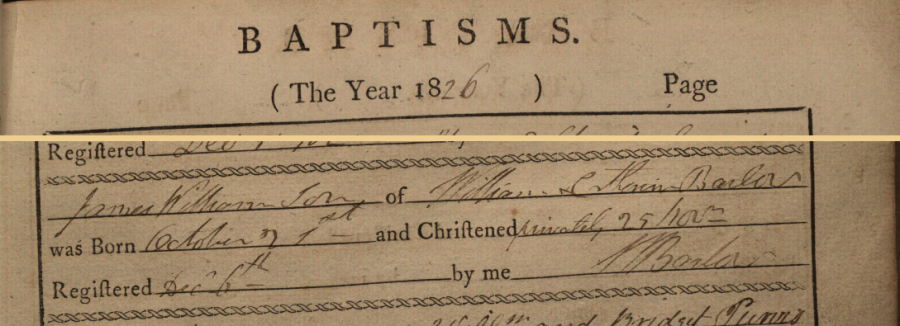

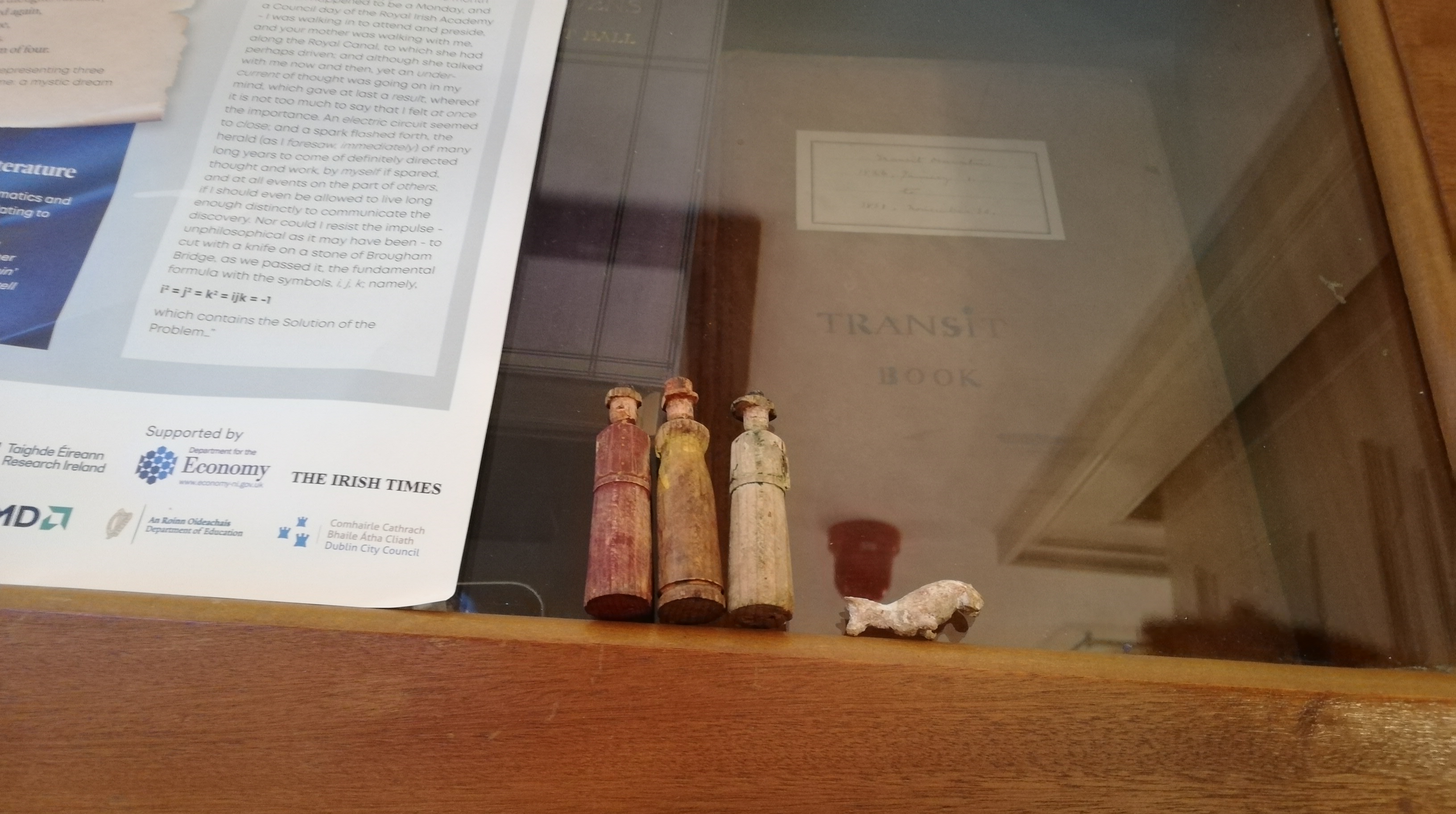

And there she showed something very impressing: four tiny figures they had found under the floorboards of their house in Edenderry. They seem to be three women, or perhaps two women and a clergyman, and a little dog.

Four tiny figures found under the floorboards of the house in Edenderry, shown here in the meridian room of Dunsink. Unfortunately, the little dog fell on its nose.

This photo is remarkable, showing the figures together with Hamilton’s fundamental quaternion equation, a corner of a paper on which ‘a mystic dream / of four’ can just be deciphered, and a Dunsink Transit book. The other features are are reflections in the glass on which the figures were placed.

Apparently, it is not yet known how old the figures are, and fantasising that they might stem from the time Catherine Disney’s children were young is nice, yet having been found under the floorboards that would also have something sinister; as if they were hidden. Yet it seems they may be wearing felt hats, and that might indicate they are even older. The house was built, as a glebe house for the parish of Eglish in 1778, yet if the figures are older perhaps the family did not even know about them. Hopefully, someone will be able to determine the age of these tiny figures.

After the unveiling of the plaque for Hamilton we did have a short yet very pleasurable talk with Rod and Glen Smith who then had to leave. At Dunsink, Hilary Thompson showing me the figures kind of passed me by, because a lot was happening there, and I was very sorry that, after the ceremonies at Dunsink having been late for the Walk, we only saw her again for a moment. Halfway through the Walk she had to leave, and we met her at the Royal Canal when she was returning to her car at Dunsink while we had been hurrying to catch up with the group. I would have loved to have walked with her, and talk some more about the house, Catherine Disney and her son Brabazon Barlow, and about the figures.

Hopefully, Hilary Thompson will find so much information about her house that also this mystery will be solved. And perhaps, when what she will find out can be combined with what Rod and Glen know about Brabazon, there also will be found some more about Catherine Disney’s time in Edenderry.

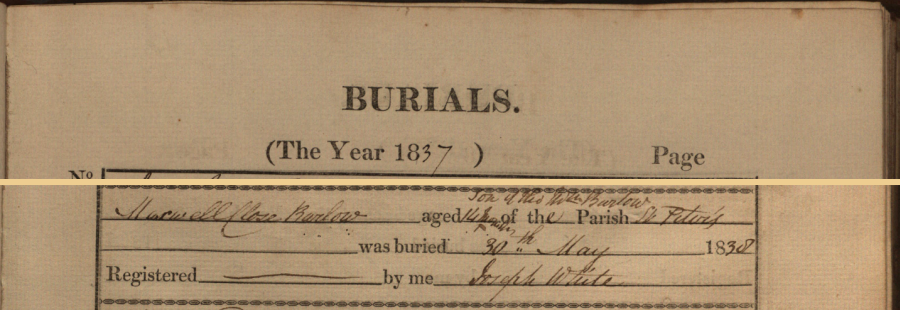

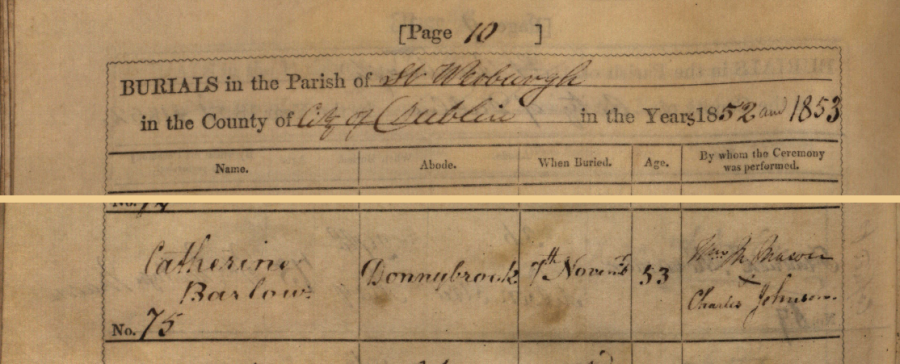

Utrecht, 8 October 2024 — Catherine’s house in Edenderry

Last February I was, to my great surprise, contacted by Hilary, the current resident of the house in the townland of Edenderry where Catherine Disney lived from late 1826 or early 1827, until 1837. It then was the glebe house of the parish of Eglish, where four of her sons were born, where Hamilton had visited her in 1830, and where he had noticed for the first time that she was not happy in her marriage.

Apparently, in Edenderry traces are left of William Barlow as curate in the parish of Eglish; “in celebration of 200 years,” the church of the Anglican parish of Eglish, Drumsallen Church,* which “can trace its history back 1500 years,” was open to visitors last September. Hilary informed me that a book was written for this celebration, and that “Rev. Barlow is noted in this book when he presided here at Edenderry.”

* Because in Google street view now also former recordings can be seen, it appeared that the recording I copied in my book about Catherine was not from April 2011 but from May 2016. Still, the exact recording is not online any more; I did remove the plane trails in the air and the electricity cables because I wanted to show it as Catherine saw it, but I did not move the bird, nor did I draw the sheep, which can be seen to be in the same position. Apparently, and understandably, the archive is only a part of the original dataset.

The current residents bought the house in 1992, and it was renovated in 1997. I sent Hilary the very last paper copy of my book, of which she sent me a photo; my book about Catherine in the house she once lived in, it still is a very strange idea. Hilary then made more photos of the house, which were astounding, I never ever could imagine that I would see something from within the house, something Catherine once saw. And at the same time it is sad, because she was so unhappy there.

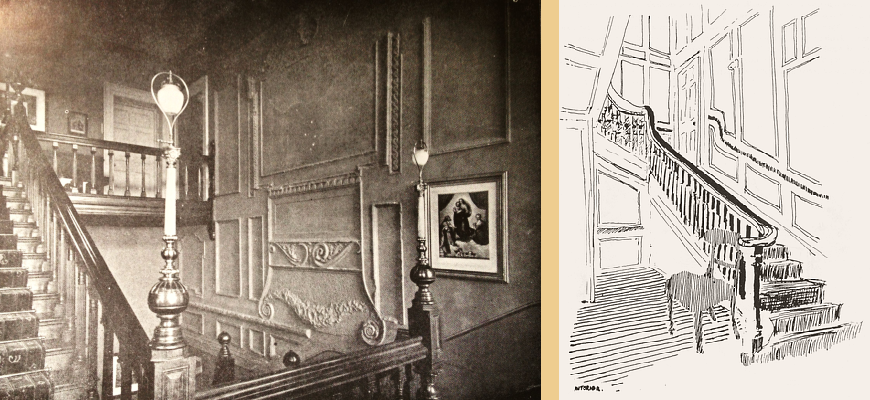

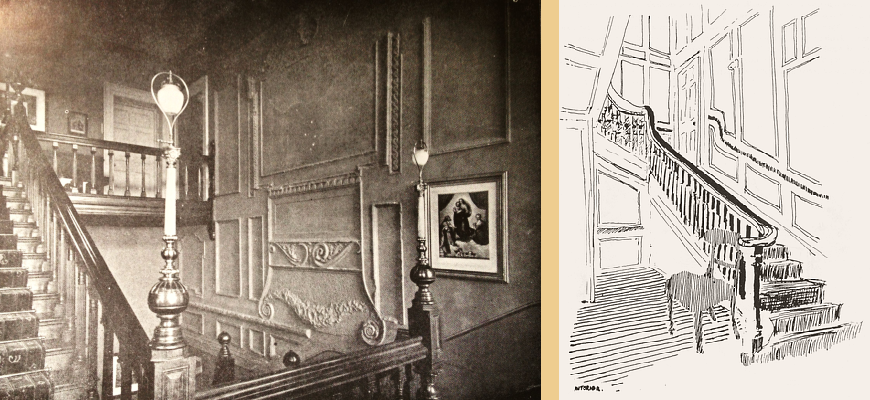

Hilary made more photos of the house; I had asked for a photo of the staircase because that was one of the few extant images of Furry Park, Killester, where she lived during her teenage years and of which Jack Kirwan had made drawings, and of Summerhill, where she lived when she met Hamilton.

Staircases of Summerhill and Furry Park.

The main staircase of Summerhill was renewed in

in the 1870s, not long before Empress Sisi of Austria came, and if this was the main one, it is not the original one. Yet such a large house must have had more than one staircase, and this one does not look large enough for giving entrance to the circa 50 rooms on the second floor. Therefore, this one may be orginal after all.

The staircase of Eglish glebe, still original.

There are more parts of the house which still are original, which means that Catherine knew them; for instance the hearth in the blue room, and a door with cameo inserts at the top of the stairs,

Original components of Eglish Glebe.

This fireplace in the blue room is the original one but “it is quite fragile.” Also original are the cameo blue inserts in the original doors.

And the beautiful view from the back side of the house,

The garden of Eglish glebe.

It is to be hoped that Catherine was able to enjoy this impressive house, which featured in Buildings in County Armagh by the late Sir Charles Brett “who described it as probably his most favourite.” That she may have found some comfort looking at the panoramic landscape, and talking with the people who lived and worked around her. And that she could be happy to see her children play outside in the lush green surroundings of the school.

Utrecht, 10 November 2021 — A Strange Land, for me beyond doubt by James William Barlow, Catherine Disney’s eldest son

A coninuation of the previous blog post

About a year ago I finally found a copy of Felix Ryark’s 1908 novel A Strange Land offered for sale, and was able to buy it. I am not a quick reader but this beautiful book was very easy to read, and for me it left no doubt any more; it felt very much the same as James William Barlow’s 1891 novel about Venus, or Hesperos, History of a World of Immortals Without a God, the only difference being that Catherine-themes were absent. I felt happy for James William because the book seems to be a less troubled remake of his Hesperos novel; although it contains his usual societal and theological criticisms it lacks the feelings of doom which are so present in the Hesperos novel. I imagined that later in his life James William had come to terms with his mental and religious conflicts about his mother’s sufferings and her afterlife.

In 1901 James William had become a member of the English Society for Psychical Research, and he may have talked with very many people about deaths and afterlife in different settings than his church; who knows, it may have helped him to make up his mind about his mother’s remembrance and find peace. In 1908, the year in which the Strange Land novel was published and a year before James William republished his Hesperos novel, he became chairman and the first vice-president of the then new Dublin section of the Society, signifying that for him these researches were important. Also his wife and one of his daughters had died already, and the three women may have become a spiritual family for him.*

* Clearly, this is speculation. And thinking about this sentence; if he still believed suicide was a sin, punished by not going to Heaven, then he also believed that his mother’s spirit was not there any more, that she had disappeared into the void he believed we all come from when we are born. A thought he fought for, because he strongly felt that no one should be tortured for infinity in order to serve as an example for others.

My son-in-law scanned A Strange Land for me, I made a searchable pdf,* a text version and epubs, see below, and not having decided yet what to do with it, I placed it on my website in the beautiful BookReader. Until I found the article discussed hereafter and in the blogpost of 8 November, which made me decide to place it online more visibly, and I uploaded it to the Internet Archive.**

* I put in the front cover twice because it is quite amazing and almost impossible to photograph; how you see the picture depends on how the light reflects off it.

** Update 12 December 2022

The speed with which Amazon picks up the full texts from the Internet Archive and starts to sell it online is impressive, and at the same time disconcerting. I uploaded the scan of my copy of A Strange Land on 9 November 2021, and already the next day, 10 November 2021, a Kindle version came online. See for how to recognise it, and a suggestion for Amazon, ASL.

In a

2021 article about Jane Barlow, Catherine Disney’s eldest granddaughter,

Jack Fennell discussed

A Strange Land, and gave arguments why he believed that instead of her father, Jane Barlow wrote it,

“The technologically advanced utopian setting [...] resonates with the Venus (Hesperos) of her father’s History of a World of Immortals Without a God [...]. A Strange Land did not achieve anything close to the popularity of Barlow’s rural Irish work, and it appears not to have been reviewed widely, if at all, by any Irish or British newspapers – however, a review that appeared in the Australian paper The Advertiser, praised the novel for its “poetic charm” and “beautiful liquid diction” (6 June 1908). [...]. Whatever the cause of the novel’s poor reception, Barlow did not try her hand at utopian or lost-world stories again, though she continued to explore the fantastic in her short fiction as the fancy took her.

[...]

The fact that James William has been identified as the author of History of a World of Immortals, despite the novel’s popular attribution to Jane,* has led some critics to credit all of Jane’s non-realist work to her father, often on grounds little sturdier than the assumption that the classical homages – particularly The Battle of the Frogs and Mice – could only have come from the Rev. Barlow’s expertise. This assumption ignores the obvious conclusion that Jane could have acquired this knowledge from her father in her childhood lessons, as well as [...] her own scholarship at Trinity College Dublin. If further proof of Jane’s aptitude for the subject be needed, a 1923 auction catalogue for the library of one John Quinn contains a number of her works, including signed copies of The Battle of the Frogs and Mice and A Creel of Irish Stories (1897), which are noted to contain a Greek inscription and a Homeric epigram, respectively.”

In the second part of these quotes Fennell is certainly right, Jane Barlow was a

talented classical scholar.** But referring to the 1923 catalogue is superfluous; almost

all her books contain Latin or Greek texts, and from for instance the text going with the poem

By the Bog-Hole it is obvious that she had read Lucretius, calling the afterlife a “great sleep.” There is indeed not any reason to assume that

The Battle was not translated by Jane Barlow; she is mentioned on the title page as the translator, and the foreword sounds like her.*** But showing that it is not impossible that she wrote

A Strange Land is not the same as showing that she did write it. The first part of the quote from Fennell’s article even shows how unlikely it is; the book “resonates” with that of her father, and she “did not try her hand at utopian or lost-world stories again.”

* Unfortunately, Fennel omits to credit Maria Devine as having identified James William Barlow as the author. On p. 126 of his book A Brilliant Void, published in 2018 and

discussed in The Guardian, Fennell wrote that History of a World of Immortals Without a God was “written either by Jane Barlow or her father (or both, in collaboration).” He therefore made up his mind after having published A Brilliant Void, and knowing from his article that he did read my biographical sketch of Catherine Disney, he must also have seen footnote 17 on page 113. Because there do not seem to have been any other discussions about this book lately, he was apparently convinced by Maria Devine’s find.

** Having been tutored at home “by the family’s governess and her father,” it is very doubtful that Jane Barlow “studied the classics at Trinity College Dublin” as Fennel claims on the first page of his 2021 article. 1904 was the first year in which women were allowed to enrol, and she also was awarded her Honorary Doctorate in 1904. Her honorary title therefore rather seems to be an open acknowledgement that she should have been allowed to study at TCD, and that without it she had nevertheless mastered her classics sublimely. Even if she may have been allowed to follow lectures without having enrolled, claiming that she “studied at TCD” thus seems too happy a statement.

*** I must say that I very much like her rendition.

I will argue here that James William Barlow wrote the Strange Land novel which not only “resonates” with his Hesperos novel; there even are very great similarities between the two novels.

Both books start with descriptions of the youths of the protagonists with which their later acts are ‘explained’; both books end with the departure of the protagonists from the ‘paradises’, which they not really are.

In both paradises

– men are the main characters,

– scientists are important,

– there are ‘swift’ vehicles,

– rocks are being blown up,

– there are no nasty or poisonous little animals; the protagonists are happy that they can safely sit on the ground outside,

– after ‘death’ there are no bodies to bury,

– the inhabitants are vegetarian; on Hesperos meat is made in a laboratory, in the Strange Land there are no animals,

– there have been times, long ago, in which the people in the ‘paradises’ were very brutal towards each other, yet they are very peaceful now,

– the inhabitants regard our Earth, with all its poverty, brutality and death, as abhorrent.

There is indeed not any trace of the themes from Jane Barlow’s books; no strong women, no real or raw direct interpersonal relationships, not even the mysticisms she used in for instance in From the East unto the West, for instance in the story An Advanced Sheet. In the Hesperos novel the protagonist learns how to teleport, about a Strange Land it would be a spoiler to mention how he entered the paradise, yet both books have a large scientific angle, even when in reality some aspects are impossible. In the Hesperos novel there is no dialogue while in the Strange Land there is, yet in both novels the protagonists remain to be outsiders and observers; there is much science and engineering; there is admiration for lovely or beautiful women. I would say that both books breathe a very Victorian male outlook on society.

Concluding, if Jane Barlow did write A Strange Land it would almost be plagiarism, and extreme scenarios would be needed to explain how this could happen. It is much simpler to assume that James William did write both books, and that having withdrawn the first edition of the Hesperos novel in 1892 he was easily convinced, perhaps by his children, to republish it in 1909, after he had published the Strange Land novel in 1908. His Vice-Provostship of Trinity College Dublin had also ended in 1908, and there was no risk any more in publishing a novel about a society as that on Hesperos which, contrary to the Strange Land society, did not adhere to the doctrines of the Anglican Church. Even though it was a society which was in the end punished for it.

Utrecht, 8 November 2021 — My imagined Catherine Disney turning into an historical figure

When I decided to write the biographical sketch about Catherine Disney’s heartbreaking story I made a decision I would not have believed I would ever make, not regarding myself as a novel writer. Yet, because there is hardly any information about Catherine Disney I did not have much choice; to show her as a real person I decided to use a mix of historic and personal data, known events and images evoked by sentences from Hamilton, extended with romantic fiction describing what Catherine may have done or thought, the only limit being that it all had to stay within the boundaries of what was known about her. I called the fiction I had inserted ‘scenarios’, and made notes whenever they were not based on known facts.

What I aimed for in my sketch was to show Catherine as a living, suffering human being to whom we could relate, who was betrayed by her family and coerced into a marriage she did not want, and through whom it would be understandable why Hamilton became so distressed; that we all would be in distress if that would happen to someone we once loved. I did not aim to describe the real Catherine or even the real James William and Jane; we simply do not know enough about them, and they may have looked at things very differently. Yet I did hope that in any case Catherine Disney would have been able to recognise the acknowledgement of her sufferings in the imaginary person I gave her name.

My goal was to show Catherine’s tragic fate so clearly that someone with more easy access to sources, being at home in mathematics and philosophy and accepting my point of view about Hamilton’s private life, and not the least, being paid to write a book, would write a new biography of Hamilton, in which Catherine’s unhappiness and Hamilton’s distress about her would receive the place it deserved, instead of adhering to Hankins’ romantic yet untenable suggestion that Catherine had been the only woman Hamilton ever loved.

But today something amazing happened. Ever since I am working on the Hamilton project, every now and then I wonder how Graves would have felt had he known how all the careful nuances in his biography ultimately disappeared as snow before the sun. How Hamilton’s story had become so very distorted over a time span of almost 150 years was fairly traceable, but it was much harder to fancy how it began. Until I found, today, an illustration of how extremely fast ideas can turn into truths, and truths lose half of their bases and become distorted. This morning I saw that Google Scholar gave a citation of my Catherine Disney sketch, in an article by Jack Fennell about James William Barlow, Catherine’s eldest son. And what is amazing is not that my sketch was cited, I am really happy with that, but how.

Reading the article about James William Barlow, I began to feel as I had imagined that Graves may have felt had he known what happened after the publication of his biography of Hamilton; Fennell’s article looks like my chapter about James William, but not quite. Not only are suggestions I made in the sketch, and scenarios I described to make it more easy to visualise how unhappy Catherine must have been in her marriage, turned into truths, also the motives I ascribed to James William Barlow, and the possible scenarios about how his ideas may have been inspired by his mother, have been completely misinterpreted and taken for real.

As an example of my romantic fiction being misinterpreted: after having mentioned that Catherine Disney had been forced to marry Willian Barlow and tried to commit suicide in 1848, in the article Fennell writes, “These events undoubtedly had a profound effect on James William’s character: since Hamilton was his astronomy professor at Trinity College from 1847, he witnessed the anguish from both sides, though he did not realise the truth of the situation until he read it in the second volume of Robert Perceval Graves’s Life of Sir William Rowan Hamilton (1882-9).” That James William only understood what had happened after having read Graves’s volume was a supposition in the scenario I was describing: it is not known when James William heard or understood that his mother had been in love with Hamilton even after her marriage. But to state that James William could see the anguish “from both sides” is not based on any facts and even very unlikely; there is not any indication that James William associated his mother’s suicide attempt with Hamilton before the latter’s death in 1865, and in Hamilton’s letters contra-indications can be recognised. The suggestion about Hamilton’s anguish suggests that Fennell did not really read my sketch and, following Hankins, still assumed that Hamilton only loved Catherine, therewith colouring his assumptions about James William Barlow.

When I found that James William had been rebuked in 1859 and read James William’s 1865 Eternal Punishment and Eternal Death, I imagined that he was actually writing about his mother about whose 1848 suicide attempt he must have known, at some unknown time after her death having made a remark about how difficult life had been for her, and about whom his Church taught that she would be ‘tortured for eternity,’ as he expressed what according to doctrine would happen in Hell. Yet in the article Fennell wrote, “Barlow’s theological outlook, influenced by his mother’s suicide attempt and the traumatic revelations of her romance with Hamilton, was unorthodox.” This is again quite beyond the boundaries of what may have happened; it is very doubtful that Catherine ‘revealed her romance’ with Hamilton to her son. But if she had told him about their youthful very happy months, and that her love for Hamilton never diminished (if that was the case), he would have known about what had happened before her death in 1853, a very long time before Graves published his biography. That contradicts Fennell’s own earlier statement that James William only realised the truth of the situation when Graves published, in 1885, the second volume. And if with the “traumatic revelations” Fennell meant James William’s reading it in 1885, it could not have influenced his having been rebuked in 1859, nor the 1865 Essay. Fennel’s sentence does not make any sense, and mentioning this seems to show again that Fennell did not read the sketch, just the chapter. My suggestions and scenarios, however much I think they might be realistic, have been turned into distorted truths.

Even worse is the ‘nothingness’ Fennell mentions. My suggestion that Catherine experienced a ‘nothingness’ (p. 73) when she made her suicide attempt, was inspired by something I had found in James William’s Eternal Punishment and Eternal Death, and in Jane’s poem By the Bog-Hole; they both describe afterlife, in case we do not go to Heaven, as a void or a nothingness we return to instead of going to Hell, perhaps after

Lucretius, making it less ‘unorthodox’ as it might seem. I introduced the idea that Catherine had mentioned her experience to her son just to associate her unhappiness to their ideas; nothing is known about what she was thinking, or what they said to each other.

But, unfortunately, in the article it became the truth; “[James William] maintained that the end of the soul was a return to the nothingness from which it had emerged at birth – a belief scholar Anne van Weerden puts forward in her biographical sketch Catherine Disney, and feels was likely inspired by his mother’s description of the peace she had felt following her suicide attempt.” Clearly the first part is simply incorrect; both James William and Jane Barlow believed in Heaven, the ‘nothingness’ was for people who according to church doctrine would have gone to Hell. The second part is completely turned around; instead of my having found the ‘nothingness’ in James William’s and Jane’s work, Catherine now told her son about the nothingness. Which is absurd, because Jane’s quote going with the poem ‘By the Bog-Hole’, ‘Non omni somno securius exstat’, shows that in any case her idea, and perhaps that of her father, of a void, or nothingness, or the great sleep as she called it, came from, or was associated with, Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura.*

* Volume 3 line 975. Note: “Our state after death will be as it was before our birth: thus Nature shows us that there is nothing to fear.”

It is a pity that, when discussing James William’s Hesperos novel, in the article nothing is said about Van Varken’s extremely miserable youth which James William describes penetratingly; not mentioning it takes out the logic of the actions of the protagonist; he just becomes some unintelligible psychopath, torturing British sailors at will. Not that this Dutchman was in any way kind, yet he was extremely scathed. But even stranger is Fennell’s remark that on Hesperos “in the event of a serious traumatic injury, surgeons euthanise the patient so that he or she will be resurrected in perfect health at the southern pole. One can easily detect the lingering trauma of Catherine’s suicide attempt in this restorative destruction – and also, perhaps, the guilt that Barlow might have felt at owing his existence to his mother’s misery. On Hesperos, there is always a chance to escape intolerable circumstances, and there is no moral judgement of those who do so.”

This is a very far-fetched idea, and there is much to say against it. Catherine’s misery was certainly not easy to recognise in the sf novel; if it had been I would not have been the first to do so. And the reason I saw it was because I was deeply immersed in the researches concerning Hamilton’s private life, having found that he sincerely loved his wife. What I therefore recognised was Catherine’s mental imprisonment in her forced marriage, while the Hesperos society would have allowed her to leave the husband she did not love.

But where it really goes wrong is where Catherine’s ‘trauma’ could be ‘detected’; according to Fennell in her suicide attempt and the “restorative destruction” on Hesperos. Suicide was not necessary on that planet; when one’s pain or suffering exceeded one’s joy or satisfaction by a certain fixed measure, the person disappeared; this was called the Second Law of Evanescence.* The reasons for evanescence could therefore be mortal lesion, or mental suffering. It could be argued that that did show James William’s anguish about his mother’s suicide attempt because on Hesperos she would not have had to commit suicide, she would simply have disappeared. But it is superfluous; the reason she wanted to commit suicide, having been trapped in her marriage, would not have happened in the first place. Had she lived on Hesperos, she even could have married Hamilton many times in their infinite existence.

* Later in the story it appeared that these people were found restored on the other side of the planet.

Something else is that Fennell somehow ascribes to James William Barlow a profound existential doubt, suggesting that he might have felt “guilt” “at owing his existence to his mother’s misery,” and that that also might be recognisable in the “restorative destruction” of evanescence. I cannot say in any way whether or not James William intended the process of evanescence to depict or represent that, yet I did not recognise such guilt in the Hesperos novel, nor in his other work. What was so very easy to see is the subject of divorce, which was allowed on Hesperos but not possible for Catherine. James William discussed the Hesperian divorces extremely cautiously, and in 1909 a

reviewer (p. 102) even wondered why he had written about it.

Yet the doctrine that God has a place in every marriage, where wedding vows have been exchanged before the altar, even when coerced, and which therefore no man may put asunder, is something James William apparently agreed with as a true member of the Anglican Church. He did not grant this alternative society happiness without a God, and a society allowing divorce could therefore not have been an alternative for his mother. That she would not be punished for Eternity, but would return to the nothingness we all come from, seems to have been the consolation he could find, that is, again, as I imagined things; James William never said anything about his mother in connection to his written works. The only known sentence he said about his mother concerns her death; that he knew “the change a happy one for her, as she was for so long a time in a very great mental affliction and depression.”

Lastly, as far as I know Maria Devine, who is not at all mentioned in the article, was the first to notice (p. 7) Jane Barlow’s letter to Alfred Russel Wallace, in which she credits her father with the writing of the Hesperos novel; until then both Jane and James William had been named as the author, without any decisive proof. But I can be mistaken; if somehow I was -not- the first to connect James William’s work with Catherine’s sufferings, and Maria Devine was -not- the first to attract attention to Jane’s letter, please let me know. But for now Maria Devine should be credited with this find, something Fennell unfortunately omits.

Utrecht, 20 September 2020 — Furry Park House Killester

Writing my biographical sketch of Catherine Disney, searching for the places where she might have lived I had found many advertisements placed by her father Thomas Disney, in which he gave his office addresses. Because it was apparent that both the first address he gave, Kilmainham Hospital, and the last one, 4 Westland-Row, were also the family’s residences, I had assumed that whenever he could, he would hold office in the family residence. But when lately someone sent me some chapters of the 1995 book The Disneys of Stabannon by Hugh Disney, I read to my amazement that in 1813, when Catherine’s eldest sister Jane married John Barlow, the Disneys lived in Furry Park House in Killester. That address had not been amongst Thomas Disney’s office addresses.

I therefore did a new search and came across a pamphlet, Furry Park House - a short history, written in 1985 by Seamus Cannon and published by the Furry Park Action Group. This group aimed to protect the house from demolition, in which they succeeded. I was able to buy a copy, hoping that in the description of the history Thomas Disney would be mentioned. On the first page the house is described, “Furry Park House is situated off the Howth Road, in Killester, Dublin. Built in 1730 it is a building of national importance, both for its architectural merit, and an account of its association with people and events prominent in Irish history.” And to my happiness Thomas Disney was indeed mentioned as one of the occupants of the house.

A 2019 Google Street view recording of Furry Park House as seen from Howth Road, Killester.

It soon became obvious that the Disney family lived there in 1812 and 1813, but I could not find confirmations for other years. Yet there is much information about Furry Park House on the internet, and combining several sources it was possible to infer from it, albeit crudely, a lower and an upper bound for the Disneys having lived there. It appeared that around the 1800s the house was bought and sold by various people, who then regularly rented it out. Also the Disneys lived there as tenants.

The upper map is from

Griffith’s Valuation, made between 1847 and 1864.

When in 1813 Catherine’s eldest sister Jane married John Barlow she came to live at Sibyl Hill House, only about 500 m from her parent’s house, Furry Park. On the satellite map the houses still can be seen, although Furry Park House is much smaller now.

Furry Park and the Disneys

According to the 2004 Henrietta Street Conservation Plan, in 1780 Richard Boyle (1727-1807), 2nd Earl of Shannon, “purchased No. 12 Henrietta Street, and amalgamated it with No. 11, already in the possession of his family.” To which The Irish Aesthete adds that Boyle “became known as ‘the Colossus of Castlemartyr’ (the name of his country seat in County Cork) due to the power he wielded by controlling so many electoral boroughs. If only for this reason, he needed to have a residence close to the centre of power in Dublin and thus settled on linking the two houses.”

The Furry Park House pamphlet mentions that, also in 1780, Boyle bought Furry Park, for “£1,300.00 plus £100.00 per annum (to value these amounts see Measuring Worth). Richard Boyle was a member of Parliament and required a convenient residence while Parliament was in session.” According to The Irish Aesthete, “He held [...] the title of First Lord of the Irish Treasury, only relinquishing the position in 1804 in return for an annual pension of £3,000; he would die just three years later.”

Because Boyle died in 1807 at Castlemartyr, he will have left Dublin in 1804. But apparently Thomas Disney did not yet come to live in Furry Park then; from 1797 he had placed advertisements giving his address as the Royal Hospital in Kilmainham, where he had apartments. As was inferred from the advertisements, in 1804 he became agent for the Earl of Darnley; on 25 October Disney placed an advertisement in Saunders’s Newsletter for property to be let, and “Propofals in writing will be received for both lots, Thomas Difney, Esq. Royal Hofpital.” Advertisements giving his Royal Hospital address were found until 22 July 1805 (searches including Difney and Difncy), then for some months no more advertisements appeared. On 9 January 1806 Thomas Disney gave his office address as Merrion Street.

It thus seems reasonable to conclude that Thomas Disney moved his family to Furry Park in the second half of 1805, but a problem is that his son Lambert Disney, the only son for whom an actual baptism record was found, was baptised in 1808 in Glasnevin by Robert Disney, Thomas’ brother. I therefore had assumed that after leaving Kilmainham Hospital the family moved to Merrion street, and then to Glasnevin.

Listing the addresses in Thomas Disney’s advertisements, it appeared that from January 1806 he held office at 31 Upper Merrion street, then from October 1809 at 33 New Gardiner Street, from August 1810 at 32 Lower Gardiner Street. No advertisements were found for 1811 and 1812, then in January 1813 he held office at 38 Gloucester Street. From June 1813 until January 1815 there are no advertisements giving his address, only one indicating he is working for Lord Darnley, but in January 1815 his address is again given as 38 Gloucester Street. It can thus be assumed that he also worked there in the meantime. Because his daughter Jane married in October 1813, and the note gives Thomas Disney’s address as Furry-Park, it can be inferred that he then thus did not work from the family residence, and that my assumption had been incorrect. Yet in September 1822 Thomas Disney moved to 4 Westland-Row; at that address children of family members and household staff were born or baptised, and others died.

Owners and occupants

It was mentioned already that in 1780 Furry Park House had been sold to Richard Boyle. In 1791 it was occupied by William Walcot (1756-1807). In 1792 an advertisement in the Dublin Evening Post reads, “Mr. Walcot’s elegant villa of Furry Park, near Clontarf, is taken by Mr. Cooke [(1755-1820)], the Secretary of War, for his country refidence.” In 1797 Edward Cooke still lived at Furry Park, “The Lord Lieutenant [John Fane, 10th Earl of Westmorland] is to have it had in contemplation to refide during the fummer, in Mr. Sec. Cooke’s beautiful villa Furry park.” Cooke returned to England in 1800 or 1801.

On the website of the Walcot Family of Walcot, Shropshire, it is mentioned about Maj. William Walcot that he was of “Ferry Park, Dublin, and Moor Hall, Shropshire.” It cannot be derived herefrom where he died, but in 1818 Anne Walcot married; she was the “eldest dau. of Maj. William Walcot of Perry Park, near Dublin.” This might mean that Walcot had returned and spent his last years at Furry Park, and that he died there in 1807, the year that also Richard Boyle died.

Note: In December 2020 I was contacted by Benjamin Bather, one of Walcot’s descendants; Major William Walcot (1756-1807) (sometimes Walcott) was his 4 times great-grandfather. Walcot was a Customs Officer, in 1784 he was a Landing Waiter, and between 1785 and 1792 a Landing Waiter for Drugs (a customs officer who enforced import-export regulations and collected import duties, etc. from vessels). He lived in Furry Park House from 1786 until 1792. More information can be found in The Walcots of Birmingham and Bristol by Michael and Patrick Walcot. Any new data will be added to the overview of owners and occupants below.

I could not find who then lived at Furry Park, but in August 1810 an advertisment was placed in the papers; someone living in or owning Furry Park had gone bankrupt, moved or died, “Furry Park near Clontarf. Houfehold Furniture, Superb Paintings and Prints, To Be Sold By Auction, On Monday the 13th day of Auguft, 1810, The entire houfehold furniture, paintings and prints, a large telefcope, three draught horfes, farming and dairy utenfils, &c. &c. The fale to begin at 12 o’clock, the paintings and prints to be fold the firft day at two o’clock. W. Jones, Auctionier.”

It thus seems reasonable to assume that after the house had become vacant, Thomas Disney moved his family to Furry Park. It is even possible that Thomas Disney was agent for the Boyle family because he would also be agent when Furry Park was for rent in 1835, see below. He may have done the same as he later seems to have done when he was agent for Lord Langford and lived at Summerhill; rent the house which had become empty and live there with his family as long as that was convenient for both parties.

Then, in 1812, “Mrs Disney, Furry-Park” subscribed, for two copies, the book Cumbrian legends, or, Tales of other times, by Mrs F. Ryves, Frances Harding (1756-1817). This is therewith the earliest time it is certain the Disneys lived at Furry Park. And as mentioned, in October 1813 Catherine’s eldest sister Jane married, the family note reads: “Married, At Clontarf Church, by the Rev Brabazon Disney, John Barlow, of Sibyl Hill, in the County Dublin, to Miss Disney, eldest daughter of Thos. Disney, of Furry-Park, in the same Co. Esq.” It therefore is in any case certain that Catherine lived at Furry Park House in 1812 and 1813.

It is mentioned in the Furry Park House pamphlet that after the Disneys the house was occupied by Thomas Burton Vandeleur (ca 1767-1835), who indeed occupied Furry Park for instance in 1828. On Sunday 14 June 1835 Judge Vandeleur died “at his seat, at the north suburbs of this city,” and on 26 June an advertisement appeared in the papers, “To be let,” “the House and Demesne of Furry Park,” “Proposals will received by Thomas Disney, Esq., No. 4, Westland-row, where Tickets for viewing the place may be had.” On 3 and 4 July the household furniture of Vandeleur was sold by auction, and the advertisements for letting the house stopped some time after 10 September. In any case in

April 1836 Thomas Bushe (1801-1862) lived at Furry Park.

Also Bushe may have rented the house as a tenant; Griffith’s valuation does not seem to give John Barlow as the owner of Sibyl Hill, and neither Thomas Bushe as owner of Furry Park. In 1848 the “Immediate Lessor” of the “House, offices, and land” of the townland of SibylHill was John E.V. Vernon, while John Barlow was given as Occupier. Likewise for Furry Park, in 1848 the “Immediate Lessor” of the “House, offices, and land” of the townland of FurryPark was John Barlow, the Occupier was Thomas Bushe. What thus seems most likely is that John Barlow rented both townlands from Vernon, and then subletted the townland FurryPark with its House to Bushe.

Of course, a problem here could be that the houses had the same names as the townlands, the only difference being the space in the names of the houses. It would be interesting to know who bought or rented what, but it does not have to do anything with the Disneys any more, they then had left Killester already.

What now is known about the history of the house (I will update whenever I find or receive more information).

1730-1748(?): Furry Park House was built in 1730, as a week-end villa for Joseph Fade, who died in 1748

1748-??: occupied for a time by Peter Paumier

??-??: owned by Charles O’Neill

1765-1780: owned by Edward Howard

1780-??: owned by Richard Boyle

1786-1792: owned or occupied by William Walcot

1792- after 1797, perhaps 1801??: owned or occupied by Edward Cooke

????

1810(?)-1813, perhaps until 1822(?): occupied by Thomas Disney (as agent for Boyle, John Barlow, or John E.V. Vernon?)

(?)1828-1835: owned or occupied by Thomas Burton VandeLeur

1835-1874: occupied by Mr and Mrs Thomas Bushe, owned by Barlow or Vernon

1874-??: owned by Ralph Smith Cusack

??-1920: owned by M. Fetherston Whitney

1920-??: owned by Crompton and Moya Llewelyn Davies

From the late 1930s it became residential housing.

Catherine Disney and Furry Park House

Yet the question still is when exactly the Disneys left Furry Park; it may very well be possible that they lived at the house until 1822, when Thomas Disney placed advertisements, that in September “Mr. Thomas Disney, has removed his Office from No. 38, Gloucester-street, to No. 4, Westland-row, Lower Merrion-street;” it contained a house, offices and a yard.

This all would mean that Catherine lived in Killester in 1812 and 1813, but probably much longer, from 1810 when she was ten years old, until 1822 when she was twenty-two. Coincidences are very common in the stories of these families; if this is correct, then Catherine spent her teens living at Howth Road (between the house numbers 219 and 243), just as her granddaughter Jane Barlow later would, also The Cottage in Raheny is on Howth Road (nr 476).

The 1985 Furry Park House pamphlet contained two marvellous drawings. One is from the back side of the house, of which I could not find any photo. The second one, a staircase, is remarkable because also in case of Summerhill, where Catherine would meet Hamilton in 1824, next to the photo of the hall which I used for the cover of my book the only picture of the interior is a staircase. The drawing does suggest an “impressive interior,” as Maurice O’Sullivan wrote in his 1933 book Twenty Years A-Growing (translated from Irish by Moya Llewelyn Davies of Furry Park House and George Thomson). It must have been a beautiful house indeed as can be read in the quote the pamphlet gives from O’Sullivan, “Isn't it a fine life is given to some rather than others! I don't know what in the world could trouble the man who lives here, though I have often heard it is they who are the worst for discontent. It is a great life. He would only need to sit outside his castle listening to the music of the birds for all the sorrow to be lifted from his heart.” If Catherine had a happy childhood, as she seems to have had, she will have been very happy here.

The back side of Furry Park as drawn by Jack Kirwan for the 1985 pamphlet about Furry Park. Courtesy Seamus Cannon.

Interior. Drawn by Jack Kirwan for the

1985 pamphlet. Courtesy Seamus Cannon.

Utrecht, 22 August 2020 — A second portrait of Catherine

Early in August someone sent me a picture of Catherine which was shown in the book by Hugh Disney (1995), The Disneys of Stabannon : a review of an Anglo-Irish family from the time of Cromwell. Seeing the picture was a great surprise; it did not look very similar to the first portrait. When I had found the first photo, which is kept at Trinity College Dublin Library, an art historian had told me about the ‘image codes’ of the early nineteenth century, in this case how to paint or draw a beautiful woman, and how the first portrait largely complied to those codes. This time he commented, “She certainly was pulled through the stylistic mold of the early nineteenth century. Quite typical Pride and Prejudice.”

At first I was a bit sad that I had not seen this picture earlier, so that I could have used it for her biographical sketch. But that feeling soon disappeared when I realized that had I used it then, she would have become completely angelic, whatever I would have written about her. Having heard about the image codes I had commented that I should have made her nose smaller and indeed, it can now be seen that her nose was quite long, but very thin. If there is anything realistic about the portrait of course.

Something else is that this picture having been provided by Patrick Wayman, Dunsink director from 1964-1992, it must have been part of the Hamilton papers and photos which were donated to Dunsink by John O’Regan, one of Hamilton’s great-grandsons. That would imply that it was made before Catherine’s marriage in 1825, and indeed, in the larger picture she looks very young, perhaps between 15 or 18. I am very curious to know where the original photo is, or whether the original drawing still exists.

The question then remains which portrait this is; a copy of the miniature or the better portrait Louisa gave Hamilton in 1861. Catherine being so angelic here, I would guess it was the latter one, but if Hamilton preferred a copy in which he would really recognize Catherine as she had been when he fell in love with her, it might as well be the first portrait. We may never find that out.

Utrecht, 20 July 2020 — Catherine’s siblings, especially Louisa

When writing A Victorian Marriage and the sketch about Catherine, I could not find the birth and death years of one of Catherine’s youngest siblings, Louisa Disney. But in November last year Finbarr Connolly sent me information about her. It came from the civil records; I do not know why I did not search them for Catherine’s siblings. Louisa’s civil marriage record shows that, in Bangor in 1850 as Louisa Hobson, she married the merchant Alexander Reid. On 30 December 1890, four years after Alexander, Louisa died in Belfast, and completely new for me was that her civil death record gives her age as 79, she thus was born in 1811.

When writing my books I did know that Louisa married Henry Hobson in 1839, became a widow in 1847, and married Alexander Reid in 1850. In my sketch I assumed that when Catherine lived in Carlingford she and Louisa were very close, because during her marriage with Hobson Louisa lived in Ballymascanlan, “where she was surrounded by relatives,” Hamilton wrote about Catherine that she “was allowed to receive members of her own family as often as she could wish” [CD, 62], and Carlingford and Ballymascanlan are only about 20 km apart. I therefore also supposed that after Catherine’s 1848 suicide attempt it was Louisa who brought her to their brother Edward in Newtown-Hamilton, assuming that Catherine will have made her attempt when Barlow was not at home; if he would have been the risk of discovery and survival would have been to large.

In his book Disneys of Stabannon, Hugh Disney called Louisa “a flirt,” and I think that asks for some explanation. Catherine died in 1853, and according to Hankins in 1861 Louisa became fascinated by Hamilton and Catherine’s story. That is indeed easy to imagine if she had been so close with Catherine during those, for both women, difficult years. Yet it may also suggest that Catherine never revealed Hamilton’s identity to Louisa; she still was married to Barlow, and in those times marriages and feelings of love were almost forbidden to talk about. In 1861 Hamilton and Louisa met again at her brother Thomas Disney’s house, and it thus may have been Thomas who told Louisa about Catherine and Hamilton’s youthful love, and how in 1825 Catherine was forced to marry Barlow.

Or it may have been Lady Wilde who told Louisa about the early love story. She seems to have been more free minded about private matters, and to her Hamilton certainly was very open. In July 1861 he wrote to Lady Wilde about having kissed Louisa in the Meridian Room of Dunsink Observatory. He realized that he had been substituting Louisa for Catherine; “You may conclude how intimate we once were, when I mention that I found an opportunity for saying to [Louisa] (lately) that I had once [1827] wished to marry her – or rather had thought that I so wished: but found that I had sought in vain to transfer my feelings from her (by me) lost sister and that I had mistaken affection to the family, for love to the individual, in short, had confounded recollections with hopes. ... She sweetly assured me, that she knew, she understood it all.” [AVM, 321]

Around that time Hamilton sent Louisa a copy of his 1848 six-week correspondence with Catherine, and because there is no copy preserved in Trinity College Library, the only hope ever to see these letters is if descendants of Louisa have kept them. Every now and then I therefore sought for children of Louisa. It now appeared that in Leslie’s Armagh clergy and parishes a short description of Louisa’s first husband Henry Theophilus Hobson was given. Henry was a younger brother of William Hobson,* who became the first Governor of New Zealand in 1840, and named the new capital Auckland. Henry had been married to a “Miss Christmas” from Waterford, and because also Henry came from Waterford, she may have been a childhood love, and she apparently died young. In 1839, about 37 years of age, Henry married Louisa Disney.

* As judged in their time the Hobson brothers seem to have been warm-hearted people. Of William is is said in the biography, “In his official duties he strove to be just, and saw protection of the Māori as a major reason for establishing British rule.” About Henry it was written in Leslie that “He died of fever, which he contracted during the famine period, when ministering to the afflicted.”

Louisa and Henry’s first child was a daughter, who was born 12 March 1840 at 4 Westland-row, the house of Louisa’s parents. This daughter, Caroline, married 13 June 1867 Rev. Thomas Shaw Woods from Ballygowan. It is not known how many more children Louisa and Henry had, but in Armagh clergy and parishes a son is mentioned, baptised 17 September 1843, and called William Christmas. That might say something about Louisa; she apparently allowed her son to be named after the first wife of her husband. In any case from 1881 William Christmas Hobson was manager of the Bank of Ireland in Armagh and in 1882 he became a member of the Commission of the Peace for county Armagh. In August 1884 he

married Mary Charlotte Jane Sharkey, only daughter the late Rev. John Sharkey, Senior Chaplain H.B.M. Indian Service. I did not find children from Louisa’s second marriage, with Alexander Orr Reid; possible descendants are therefore of the Woods or the Hobson family.

It is not known whether or not Hamilton confessed it to his wife, but in my AVM I have shown that they must have talked with each other, and after each of Lady Hamilton’s illnesses again more openly. Lady Hamilton knew about Catherine even long before their marriage and she never made a problem of it, she even met Catherine at least once. Indeed, a story so terrible as that of Catherine, and the hard way Hamilton learned about her forced marriage throughout the years, is easy to sympathize with. Yet Lady Hamilton became ill in 1856 because, as I inferred from the letters given by Graves, Hamilton had lost himself in memories for some time and therefore had paid her less attention; if she feared for her marriage as I supposed, she will have been heartbroken and terrified in that for married women extremely harsh society. But Hamilton then took care of her for months and was so worried that he became ill himself. Thereafter, even though he remained to be sad every now and then as the romantic he had always been, his priorities had become clear again; his bond with his wife was the most important one. And even Graves commented that the Hamiltons remained attached to each other until the end.

Louisa’s name does not appear in Graves’ biography; it will have been utterly impossible for him to write about her because of the contemplations about marriage and the kiss. Both Graves, the Hamilton couple and the Disney siblings grew up during the Regency, when society was somewhat more relaxed about romance and certainly easier for women, but in the 1880s, the time of the writing of the biography, it was forbidden to talk about anything connected to marriage unless in some heavenly tone, and the kiss would have meant the end of both Hamilton’s and Louisa’s reputation. It is known that later, at the time Graves started to write the first volume, there was a correspondence between Robert Graves and Aubrey de Vere, of which the letters written by De Vere are kept in Notre Dame Library in Indiana (Manuscript and Ephemeral Collections, MSE/IR 1040). The letters are not online, but it appears that De Vere advised Graves to leave one woman out of the biography completely; that must have been Louisa. Unfortunately, the way Gaves undertook his concealments were the end of Lady Hamilton’s good reputation, and even though Graves meant to accomplish the opposite, it also was the end of that of her husband. Of their good marriage nowadays nothing is left but some sentences in Graves’ biography. Yet happily confirmed in Hamilton’s letters and love poems for his wife.

Another reason why Hamilton had decided not to pursue marriage with Louisa sheds again some light on Lady Hamilton; Louisa did not seem to be interested in science, something which for Hamilton “would weaken any affection,” as he wrote to his sister Eliza in 1827. Therefrom it can easily be inferred that Lady Hamilton did like to listen when he was talking about his work and to read about the grinding process of the telescope mirror at Birr [AVM, 182], and she was very proud of his successes. It then was indeed a highlight to have been present at the birth of the quaternions, and have seen something like that happening to her beloved husband.

Now also searching the civil records I found some more info, such as the marriages of three Disney brothers, Thomas, James and Edward. These records did not contain new information, but there was a confirmation; in the handwritten records it can be seen that Dorathea Jane Evans’ first name was indeed written with an -a-. Just as on her headstone, but the Calendars of Wills and Administrations again writes Dorothea. It must have been difficult, to have a name differing so slightly from the usual, but attention should be paid because names are obviously extremely personal.

But more surprisingly, there were also three death records of Sarah Disney’s, of which one exactly matches Catherine’s youngest sister Sarah about whom, together with their sister Patience, I had found information earlier. Sarah is described as a Gentlewoman; in Louisa’s above mentioned marriage record their father Thomas was described as a Gent(leman). It is also given that she was a spinster; it is known from her father’s letter to General Hill [CD, 19] that she was unmarried in 1838. She died in Armagh, and indeed quite a few family members lived in the North. Also the age being exactly right, it seems very likely that the Sarah Disney who died in 1878 in Armagh was indeed the youngest Disney sibling. It is even possible that she also was one of the many relatives Louisa and Catherine had contact with when Catherine lived in Carlingford. But unfortunately, I did not know about her when writing the sketch.

Still missing were the birth an death year of Susan Paton, who married James Disney. Another search yielded some results; she seems to have been born in Banff, Scotland, in 1826, and they had a daughter Susan Disney, who died in November 1940 in Eastbourne, Sussex. Because James Disney’s data given there corresponds exactly with what I had found earlier, and he also died in Eastbourne, this information may be accurate, and the birth year of Susan Paton then was 1826.

It seems that now the list of siblings is complete. And it is of course nice to know that most of my guesses were nearly correct.

Update 17 January 2021

Also about the family of John Barlow and Jane Disney, Catherine’s eldest sister who lived at Sibyl Hill, as given on p. 130 of Catherine’s biographical sketch, I found new information. Moreover, I received extracts from Hugh Disney’s book Disneys of Stabannon. I now wrote a new unpublication, correcting some errors I had made in my biographical sketch about this family, and commented on the for this family relevant parts of Hugh Disney’s book: Jane Disney, John Barlow, and their children.

Update 10 March 2024

In my biographical sketch of Catherine Disney, in footnote 21 on p. 61 I had given a quote about her brother Henry Purdon Disney from The Colonial church chronicle and missionary journal, “Mr. Disney did not enter Holy Orders at his first outset in life. He held for some years an employment under the Board of Ordnance [...]; but he was desirous of entering upon a life of greater usefulness, and had fixed his thoughts upon taking part in the Christian ministry; so that he eventually resigned his appointment, and, at his ordination [in 1837], entered the service of the Church, in Ireland, as a curate [...].”.

Two weeks ago I was contacted by John Falvey who had found information about Henry Purdon Disney at the National Archives, in the Miscellaneous section of the ‘Birth Certificates, Wills and Personal Papers’ of Officers in the War Office. The first surprise was that I had not known what the Board of Ordnance was; because I only knew the word Ordnance from the 1846 maps of Ireland, I simply had assumed it was something Geological. The record Falvey had found was Henry’s Birth and Baptismal Certificate (choose ‘Preview an image of this record’, then p. 1879), written by Henry’s father, and a note showing that Henry had been a Clerk in the Principal Store Keeper’s Office (p 1877).

On the last page (1881) it is written “Office of Ordnance 6th December 1826. Recd 6 Nov. C/1295. Sir His Grace The Master General Mark Singleton Esq. having appointed Mr. Henry Disney to be a Clerk in the Office of The Principal Store Keeper. We beg leave to acquaint you for the Board’s Information that we have this day examined Mr. Henry Disney upon the several points prescribed by His Grace and The Boards’ Minute of the 21st July last 1824, and are fully satisfied as to his capability for the situation to which he has been appointed. We are Sir your most obedient humble Servants. William Griffin Esqr. [Secretary to the Board], six signatures.”

In the ‘Birth and Baptismal Certificate’ (p. 1879) itself, Thomas Disney had written, “We do hereby certify that Henry Purdon Disney was born in Merrion Street Dublin on the 2d. of November 1805 & privately baptized in said street in December in said year. Given under our hands this 9th December 1826. Tho[ma]s Disney, A[nne] E[liza] Disney, Parents of said H.P. Disney.“

That Henry was born at Marrion street in November 1805 was a surprise. After having finished the biographical sketch I had started to doubt whether or not the family resided at the addresses Thomas gave for his offices as I had assumed. It was certain that at the time Catherine was born the family lived in the “Royal Hospital near Kilmainham”, and I had written that ‘at some time between April 1805 and January 1806 Thomas Disney had moved his offices to 31 Upper Merrion Street.’ But only about Westland-row, where Thomas moved his offices to in September 1822, it was certain that also the family lived there; not any confirmation was found for the years inbetween. Furthermore, it still is unclear why in 1824 and 1825 the Disneys lived at Summerhill House, and I have never found Furry Park, Killester as an office address. But Henry Purdon Disney’s record now confirms that in 1805 the family moved house with Thomas when he moved his offices to Merrion Street, and it indicates a somewhat more precise time frame.

Assuming that ‘George Disney’ was a printing error and should have been ‘Thomas Disney’, from perhaps 1796 but in any case 1797, until and including 1805, in the Gentleman’s and Citizen’s Almanacks, Thomas Disney is given as the Auditor and Register at the Royal Hospital. The Almanack of 1806 reads, “Auditor and Register Thomas Disney, and Ralph Smith, Esqrs,” and in 1807, only Ralph Smith is given. Often, when Thomas moved his offices, for a while he gave both addresses in the advertisements, and that may also have happened this time; rounding up his work in the Hospital and starting up his business in Marrion street, the family moved out at some time between April, as I had found when I wrote the biographical sketch, and November 1805. Catherine, born at the Royal Hospital, thus came to live at Merrion street when she was five years old.

It is nice to know now that Henry was indeed older than James, as I had expected, and Henry’s age as given on his gravestone is indeed correct, but I had not really expected that his age in his TCD admission record, which was given as 16, was a year too young. John Falvey wrote, “Trinity College records often over-state the student‘s age, this is the first instance I’ve seen where the age has been understated.”

Including the adaptations from after publication of my biographical sketch, the 15 children and 10 children-in-law of Thomas Disney and Anne Eliza Purdon, who married in July 1791, were:

Jane (1792/1793-1865), m. 1813 John Barlow (1791-1876)

Brabazon (1794-1833)

Patience (1795-1795)

William John (1796-1813)

Anne Eliza (1797-1839), m. 1829 John James Disney (1805-1865)

Thomas (1799-1889), m. 1847 Dorathea Jane Evans (1823-1896)

Catherine (1800-1853), m. 1825 William Barlow (1792-1871)

Robert Anthony (1802-1885), m. 1841 Caroline Disney (1810-1855)

Edward Ogle (1804-1882), m. 1854 Matilda Miller (ca 1816-1881)

Henry Purdon (1805-1854)

James (1807-1896), m. 1851 Susan Paton (1826- ..)

Lambert (1808-1867), m. 1835 Anne Henrietta Battersby (ca 1815-1873)

Caroline (1809/1810-1839)

Louisa (1811-1890), m. 1839 Henry Theophilus Hobson (1802/1803-

1847), m. 1850 Alexander Orr Reid (ca 1809-1886)

Sarah (1813-1878)

Utrecht, 22 February 2020 — Remarks from Hamilton’s notebook containing notes from 1853

When we were in Trinity College Library last summer, we saw Hamilton’s notebook containing both 1848, the year of Catherine’s suicide attempt, and 1853, the year of her death. The notebook contained the two quotes which were given in the book Myths Exploded, as given below, about Hamilton’s “secret petitions,” clearly showing his distress after Catherine’s death, and James Barlow’s remark, about how terribly unhappy his mother had been.

Yet the notebook contained more surprises, again explaining remarks and events. I had planned to work them out before writing about them, but time and circumstances makes that something for the very long run. I will therefore give them now, and perhaps later write some more, or further correct them.

Very remarkable, but not changing the story as given in Catherine’s biographical sketch, is that apparently Brabazon suffered a severe accident in his childhood, causing him to fall behind at school. Changing the story a bit is that when Catherine died, her sons Brabazon and Arthur were not at home, they were at sea. That means that of her sons only James William and Thomas Disney may have been present when Catherine died.

Quite amazing is that Hamilton wrote about Catherine feeling very guilty about the death of John Lambert, whom they apparently called “Johnnie”; he died in 1849, when he was only eight years old. He died less than a year after her suicide attempt, and she had been afraid that he had died because of her neglect, something she must have told Hamilton in one of their two ‘parting interviews.’ It underpins the idea that she indeed suffered very much from feelings of guilt, as I had suggested in my biographical sketch, yet now it seems to have been even more intense than I had assumed, and lasted until her death instead of until her separation of Barlow, as I had hoped for her.

In that sense even more remarkable is that she did not write her heartbreaking sentence, “to the mercy of God in Christ I look alone, for pardon for all my sins” as a conclusion of the 1848 six-week correspondence, as I had understood, but she said that to Hamilton in one of their parting interviews. It again emphasizes that she remained very unhappy until her very last days, which explains James Barlow’s remark after his mother’s death, that he knew “the change a happy one for her, as she was for so long a time in a very great mental affliction and depression.” It is sad; even her last years were less quiet than I suggested in my sketch; they had seemed unhappy enough already.

All this openly shown unhappiness must also have made the parting interviews even more difficult for Hamilton than I had suggested; he must have been devastated not only because she had loved him and he had not known about it, but also that she was even more unhappy than he had known already. It makes his hatred against Barlow even more understandable, and it is a good thing that he did not have it in him to really act upon such feelings. Without revealing her identity other than to her family and Lady Campbell, he started to write about Catherine and her unhappiness, and wrote very many letters. Which he certainly will have needed, as a married man not being allowed to talk about it openly.

Leaving Parsonstown on 12 September 1848 and returning later that month

Lasty, there was a big surprise. The notebook contains a copy, in shorthand, of a letter sent from the Observatory on 21 September 1848, to James William Barlow, Catherine’s eldest son who apparently was in Carlingford, where his parents and in any case their youngest son Johnnie then lived. It might mean that my suggestion that Hamilton remained in Parsonstown after 12 September is not true. I asked Birr Castle whether they could shed light on the dates of Hamilton’s visit to Parsonstown, if he perhaps left but returned for a second time, but unfortunately, the oldest Visitor’s Book is from 1850. It therewith appears to be beyond my capabilities to really solve this riddle.

Yet it does not say that Catherine wrote her suicide letter in September, as Hankins suggested. While being in Parsonstown Hamilton wrote happy letters about his visit to James William Barlow, which would have been almost cruel had he known that James’ mother just had tried to commit suicide. Likewise, in the letter of 21 September the word Quaternion can be deciphered, and again that would be quite insensitive in such circumstances. Hamilton moreover sent the letter to Carlingford, allowing for the possibility that James’s father would see it, only some weeks after his wife would have tried to commit suicide. Knowing how honest Hamilton was it is completely unimaginable that Hamilton would do something like that, and risk bringing James in such a difficult position.