Introduction

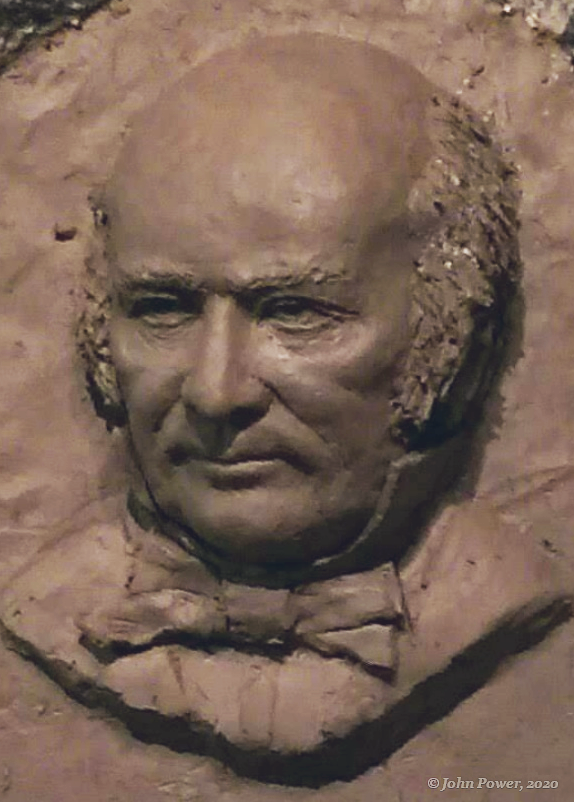

Sir William Rowan Hamilton was Ireland’s greatest mathematician, Andrews professor of Astronomy at Trinity College Dublin, and Royal Astronomer of Ireland. Born in Dublin in 1805 and grown up and educated in Trim, having been a child prodigy Hamilton became Astronomy professor in 1827, shortly before his final exams, and then moved into Dunsink Observatory where he would live for the rest of his life. In April 1833 he married Helena Maria Bayly, born in 1804 and living at Bayly Farm in Nenagh Tipperary. It was a good marriage, blessed with three children; William Edwin was born in 1834, Archibald Henry in 1835, and Helen Eliza Amelia in 1840. They became Sir and Lady Hamilton when in 1835 Hamilton was knighted for his discovery of conical refraction. Hamilton died in 1865 at the Observatory, and Lady Hamilton in 1869 in Donnybrook. They both were buried at Mount Jerome Cemetery.

About the distorted view on Hamilton’s private life

Hamilton’s work is highly praised;

below a short overview is given of the ungoing active use of his work. But due to an extraordinary coincidence of circumstances, nowadays the view on the Hamilton couple’s private life is very negative. During their life there had already been gossip in Dublin, but nothing more than there usually is about very famous people in very strict societies, as Ireland and England were in the Victorian era. The real distortions started when in the 1880s Robert Perceval Graves published an enormous biography of Hamilton, and on only six or seven pages criticised Hamilton and the choices he made for himself. These pages started to live a life of their own, and all the highly admiring other two-thousand ones were soon forgotten, including Graves’ positive remarks about the marriage, and his emphasizing that Hamilton was not alcoholic, as the local gossip had insisted.

Stated succinctly, Hamilton is now generally assumed to have been an unhappily married alcoholic, and Lady Hamilton a neurotic hypochondrial nobody. In my 2017 book A Victorian Marriage, actually a history essay of which a summary is given below, I extensively discussed why these views are completely incorrect, and moreover, were never intended by Graves. In the 2018 gossip article which I wrote with Steven Wepster, we showed where the gossip originated, and how it evolved throughout the twentieth century. It can easily be stated that there are very few famous couples about whom the posthumous view worsened so steadily and continuously over such a long period of time.

Unfortunately, it seems that almost anything could be added to the story of Hamilton’s private life as long as it fitted the caricature of an unhappy and unworldly genius who married a woman who could not handle him, nor the household. And even nowadays new additions still appear. To bring this process to a halt and show the Hamiltons again as the people they were, their life must be reconsidered by returning to the original sources, and their story told anew. This website is dedicated to that, by discussing details from the Hamilton couple’s private life as was found in their own letters, in Graves’ biography, in descriptions of contemporaries, church records, newspaper articles, and articles and books from those times which can be found in abundance on the web. Together they show Hamilton as a happily married family man and a very hard-working mathematician, and Lady Hamilton as the strong and loyal wife who made that possible.

A call to future writers about Hamilton’s private life

The gossip still is so bad, and the stories so distorted, that to change the narrative about Hamilton, and see him as the man he was, it is unavoidable to forget everything you thought you knew about him. From Hamilton’s private life, nothing but his name and address, birth and death years, and perhaps the given years of public events, is untouched by the gossip. Then read Graves’ biography, while keeping in mind that he wrote it, as a reverend, in a time of temperance, about a man who loved to drink wine at dinners, as many people did.

Many events being told in the caricature of the Hamiltons may seem to have happened literally, but every story has gone out of context. Events related to them were left out and forgotten, others were invented and became the apparent context, as we showed in the second part of our gossip article. The list obviously being too long to be discussed here, an example of the major distortions of the story is the view on the three long absences of Lady Hamilton from the observatory.

It is true that twice, in 1834-35 and in 1836-37, she was in Nenagh for about nine or ten months, and in 1841 she was in England. But it had nothing to do with not wanting to be at home, or not loving her husband; she did not in any way ‘leave’ him. The first and second time she took care of her ailing mother, Mrs. Bayly, who was loved dearly by both Hamiltons, but the first visit also had to do with the observatory being renovated. Their eldest son having been born in May 1834, living there in winter while the house was warmed with fires and lit with candles was not a very healthy situation to begin with, but the house at the same time being renovated and therefore regularly very dusty, could doubtless be harmful for such a young child. With the state of medicine then, it was probably just a good idea not to live there. The second time was lengthened greatly by the severe illness of Mrs. Bayly, whom they feared would die. Even though Hamilton very much missed his wife when he had to be in Dublin for duties, he was very often with them in Nenagh, feeling very happy there; he stated that at Bayly Farm he “enjoyed a most luxurious quiet.” But the third time, in 1841, was different.

Before accepting his marriage proposal, Helen Bayly had asked Hamilton to promise that he would live a retired life with her, doubtless because of her health. She usually was strong enough; she regularly rode her horse and led a very active social life, but she could fall very ill in only a few hours and then need weeks to recover. She may have been more sensitive than others to all the infectious and dangerous diseases circulating at that time, perhaps because of underlying then unknown medical conditions such as allergies, and she must have dreaded that she would suddenly fall very ill while not being in familiar surroundings. Travelling was very strenuous then, causing visits to take days or even weeks, and, this being the times of bloodletting, raising blisters, laudanum and calomel, she likely trusted her own doctors more than strangers.

Around 1838 Hamilton started to forget his promises, trying to persuade her to come with him on long visits to all the manors and castles he was invited to. She accompanied him once, on a three-week visit to the marquess of Northampton at Castle Ashby, but she must have felt awful, because thereafter Lady Hamilton, who in those for married women very difficult times did not have the means to protest against it, and moreover loved her husband and clearly wanted to grant him such wonderful visits, slowly slid into what the doctors called a ‘nervous illness’. She probably suffered from what we now would call a burn-out; the feelings of hopelessness in an overwhelming situation one does not seem to have any influence on, leading to physical, mental and emotional exhaustion. When she had finally fallen ill Hamilton did listen; he changed his behaviour and such visits were never repeated.*

* In 1853, she did accompany him on a visit to the Queen who was in Dublin, but that invitation was received on the morning of the day of the visit. She may have felt well that day, and therefore could accept.

Later in life she fell ill once again, and that had to do with Hamilton’s grief after the death of Catherine Disney, or rather, with a long trip down memory lane in 1855. When Lady Hamilton fell ill, Hamilton was very worried about her, and took care of her for months, this time at the observatory. After her recovery, it never happened again.

But Graves only saw illness and burden; he did not recognise how hard Hamilton, and his wife, had to work to keep him from becoming vain; Graves just saw his friend as a “simple, zealous man.” He also does not seem to have had any idea about what it takes of the family of a mathematician who works at the lonely heights Hamilton had reached. During the largest part of Hamilton’s marriage Graves did not live in Ireland but in England, and he had no clue about Hamilton’s vivid family life at the observatory. Coming from a very intellectual, literary family at the top of society, to still show his friend’s greatness, Graves shoved the common people around Hamilton under the carpet and completely focused on eminence.

Graves wrote his biography as a defense against the alcoholic reputation of Hamilton, who even according to Graves never drank too much. But there was gossip coming from people who did not know him, and did not understand his work, as there is always gossip about famous people who do not adhere completely to the social norms set for them.* Hamilton was very self-aware and knew exactly what he needed, but Graves did not agree with the choices he made for himself; after a strange event on an evening in February 1846 his friend should have stopped drinking altogether, and if he could not, he should have chosen a wife who would have made him stop. Had Hamilton become a teetotaller, Graves would have been able to write a biography about a man he almost idolised, who was “thinking none but high thoughts,” who was, in his eyes, at the lonely heights of moral perfection.

* A good example of how Hamilton, and many people around him, loved the ‘pleasures of the table’ without going too far (and copied here from an earlier blog), was given in a 1965 article by John Reid, then acting director at Dunsink Observatory. In the article he first gave the then prevailing opinion, coming directly from Graves as was shown in our gossip article, that Lady Hamilton had not been the strong wife Hamilton had needed, but then, surprisingly, he stated that Hamilton had had a “very happy” marriage. When mentioning that Hamilton had not been able to attend the 1840 meeting of the British Association in Glasgow because of the birth of his daughter, Reid writes: “He must have regretted this, since it would have given him an opportunity to meet Encke and Jacobi. On the one occasion on which he did meet the latter [at the 1842 Manchester meeting of the British Association], each of them was left with a deep mutual respect for the other’s drinking prowess.” Hamilton thus was not the only one; gaining a deep mutual respect shows that they drank publicly, and it sounds as if they were very much enjoying themselves. But Jacobi did not have such a bad reputation already, and he was never called alcoholic.

What also was in the letters in the biography, but not recognised by Graves and thus causing the most important omission in his opinion about Hamilton, was the change in Hamilton in the summer of 1832. He made a psychological discovery which completely changed his life, or rather brought himself back to the happy, very self-assured man he had been before having lost the two other loves of his life, Catherine Disney and Ellen de Vere. Not having had a clue about how to cope with such feelings, that summer Hamilton discovered what to do with himself, and he never became so melancholic again. But psychology not having been developed yet, Hamilton’s friends did not understand what it was all about, no matter how clear Hamilton was about it, and how often he later referred to it. It pleads in Graves’ favour that also Hankins, his second biographer, did not recognise it, but that also coloured his biography, and was the direct cause of the greatest distortions.

But in the end, Hamilton was very lucky to have had a friend who so extensively wrote about him, and even more important, who gave so many original letters. If Graves had not done that, and had not written everything down in such minute detail, Hamilton’s notes showing his repeated distress about Catherine Disney would have been found out of context, the amount of notes being so great that it took Graves twenty-five years to sort it all out and write the biography. Hamilton could not openly write about what had happened to Catherine, marriages were sacred then. He therefore could not accuse her family and her husband of having destroyed her, he could only express his own feelings. Without having read his own remarks about his important psychological discovery, and about his great attachment to his wife, we now would have an even more distorted view on Hamilton than the alcohol-gossipers already gave us.

So let us be grateful for Graves’ enormous efforts, but stop treating his opinions as an objective, or even impeccable source. Let us stop the gossip and see Hamilton as the mathematician, the family man, and the affectionate husband he was.

Description of the pages on this website

I started this website in 2015, when I was writing my first essay about the happy marriage of Sir and Lady Hamilton. It consist of five main pages.

VictorianMarriage.html where my two essays, publications and unpublications are listed, and every now and then I write blogposts about for me new details or new insights.

VictorianMarriage_2015-2019.html which only exists because the main page, the previous one, became way too long. But the main page contains links to the blogs on both pages in its sidebar.

HamiltonPhotopage.html is filled with photographs of Hamilton’s family, friends and colleagues, to get some notion of what people looked like in those days, and placing the Hamilton photos into perspective.

CatherineDisney.html is dedicated to the very unhappy life of Hamilton’s first love Catherine Disney; I wrote my second book about her. On the one hand to show that it was not at all strange that Hamilton was periodically upset about her fate and that that had nothing to do with his own marriage, but also because her very sad story was in itself worth to be told. Forcing people into marriages they do not want to be in should not be possible anywhere at any time.

Miscellaneous.html is partly connected to Hamilton, and partly to my former physics study, which was interrupted when I stumbled on the very strange stories which were told about the Hamiltons.

The website is ongoing work, yet I hope that some day the view on the Hamiltons’ private life becomes as positive as they deserve, and this work will be finished. What I really hope for is that someone will write a new biography; for such an extraordinary story three main biographies written in three different times are certainly not too many. I then hope it will be someone with a thorough knowledge of all sides of Hamilton's scientific life, from his mathematics to his metaphysics, combined with theology, psychology, literature and history, who is prepared to take the gossip out of the stories, and will make good use of all the tiny details I found to be incorrect or simply missing. Such a new biography would, in one stroke, change the views on Hamilton. While the mathematicians, physicists, computer scientists, engineers, etc. carry on the work following from Hamilton’s enormous legacy, of which a glimpse is given below.

And then I hope for a beautiful costume drama, in which Hamilton’s love for Catherine Disney is embedded in the terrible story of her life, a love which at the same time did not in any way destroy the happy marriage Hamilton had with Helen Bayly. It will not be easy to depict this very nuanced and intricate story while respecting the people involved, but it can be an intensely sad yet at the same time scintillating story about a beautiful, talented Disney daughter who was sacrificed on the altar of family pride and was unable to cope with her fate; a kind, humble, yet also very self-assured genius who was far ahead of his time and had to endure the consequences thereof; and a happy, fashionable and headstrong woman from Nenagh, Tipperary, who with her unstable health dared to marry a man like that.

The state of science in Hamilton’s days

The engraving of the steam locomotive Hibernia, built in 1834, shows the state of science a year after Hamilton’s marriage, two years after the publication of his Third Supplement to an Essay on the Theory of Systems of Rays which would lead to Hamiltonian mechanics,* and nine years before Hamilton found the quaternions.

Having made his discoveries in a time in which telephone and radio did not exist yet, photography and bicycles were in their infancy, and people walked or travelled by horse, carriage, steam train and steamship, Hamilton’s son reported that “Sir W.” was indifferent to contemporary fame, “arising from his conviction that his belonged to a future age entirely.” Hamilton was right, yet little could he know that large parts of his work had to wait until quantum mechancis and the dawn of computers and space travel before they would start to blossom.

* For short descriptions and complete transcriptions of the original essay and the three supplements see David Wilkins, Theory of Systems of Rays.

Restoring Hamilton’s public reputation as a great scientist

However strange it may sound to someone within the Hamilton-bubble, hardly any member of the general public knows about Hamilton. Taking myself as an example, I had earned my bachelors in physics before ever realizing that there was a man behind the Hamiltonian. It was not because of happy youthful naivety; I was fifty-five already when I became a BSc, and had followed the course ‘Advanced Classical Mechanics’ and various courses about quantum mechanics, being thus familiar with the Hamiltonian as a ‘function’ and an ‘operator’. And when I did hear about the Irish Sir and searched for information about him on the internet I did not like him at all; he had married a local lass because he could not marry the woman he really loved, and made her unhappy by just working on his mathematics and depressedly becoming an alcoholic. How could he do that to her.

I was astounded when I discovered that Hamilton had not married his wife ‘on the rebound,’ and had not at all been alcoholic. Learning more about his life and work I entered the bubble in which Hamilton seems to be omnipresent, and became very surprised about why I had not heard of him earlier. Soon it appeared that during his life and in the years shortly thereafter Hamilton was seen as one of the great mathematicians as Clement Ingleby called him in 1869, and even as late as 1895 Robert Stawell Ball dedicated a chapter to him in his famous book Great Astronomers. Yet although Hamilton’s mechanics was highly praised, as for instance in this 1878 Leiden dissertation, it was not known why it would be useful.* And not only his mechanics had to wait, for even longer periods of time no one knew why to use the quaternions outside pure mathematics.

* Adriaan Kempe 1878, p 100, proposition III: “For now, the analytic mechanical considerations of Hamilton and Jacobi only have theoretical value.”

It is well-known that after Hamilton’s death in 1865 Peter Guthrie Tait continued his work on the quaternions with heart and soul, and in 1872 also his friend James Clerk Maxwell had been “getting converted to Quaternions.” Even though he wrote his Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism in “Cartesian form,” he was “convinced that the quaternions were very useful for especially electrodynamics.” He added to his results the corresponding quaternion forms, and on pp. 236-238 of the second volume he listed the electromagnetic equations in quaternion form.

But not everyone was happy with Maxwell’s use of quaternions, and, coincidentally, the second volume of Graves’s biography, which suffers from conveying to his readers a vague but unmistakable feeling of doom caused by some scattered pages with lamentations about Hamilton’s habit of drinking alcohol, was published in 1885, the same year that Oliver Heaviside argued in his article ‘On the Electromagnetic Wave-surface’ that the quaternions were superfluous, that the quaternion product was not at all necessary for physics. In 1888, a year before the publication of the third and last volume of the biography, Josiah Willard Gibbs sent copies of his unpublished pamphlet on vector analysis to Heaviside and many other scientists, and the vector wars soon followed.* Even though it can easily be argued that Hamilton would never have become engaged in such heated discussions, that he would have welcomed vector analysis as a spin-off of his quaternions,** it severely damaged his reputation.

* I did know how much the ‘vector wars”, which started in 1890, harmed Hamilton’s reputation. But until I worked with Kathy Jones on her Hamilton and Quaternions video, I had not realised that Heaviside published his criticisms in 1885, the same year Graves published the second volume of his biography, and that Gibbs wrote his pamphlet a year before Graves’ third volume was published. Nor, that Hamilton had already found the modern vector operators, and what to use them for.

** Comparing the books by Hamilton from 1866, and by Tait from 1867, the difference is striking: for Hamilton quaternions were mathematics, for Tait they were physics. Therefore, there is no doubt that Hamilton would have regarded the vector wars as paltry squabbles; it did not hurt his mathematics, and only slightly changed the apprearance of his methods applied to physics, not their meaning. He had changed science himself, and there was no reason to protest if someone else would again change it; having given his operator \(\large\triangleleft\), now called nabla or del, and written as \(\small\nabla\), and \(\large\triangleleft^{\tiny {^2}}\), now written as \(\small\nabla^{\tiny{2}}\) and called the Laplacian, he remarked, “The bare inspection of these forms may suffice to convince any person who is acquainted, even slightly (and I do not pretend to be well acquainted), with the modern researches in analytical physics, respecting attraction, heat, electricity, magnetism, &c., that the equations of the present article must yet become (as above hinted) extensively useful in the mathematical study of nature, when the calculus of quaternions shall come to attract a more general attention than that which it has hitherto received, and shall be wielded, as an instrument of research, by abler hands than mine,“ and continues by giving what is now called the gradient, and describes its use. Indeed, his \(\small \nabla\) operator and its applications effortless survived the transition from quaternion to vector physics, just as his mechanics survived the transition from Newton’s classical mechanics to Einstein’s relativity theory and quantum physics.

The damage was so thorough that nothing could reverse it any more; it was well-known that in 1925 Werner Heisenberg* and in 1926 Erwin Schrödinger published their papers on quantum mechanics with which Hamilton’s mechanics finally found its place in physics; that with the coming of computers, which do not mind long calculations, from 1958 the quaternions appeared in digital applications; that in 1967 Michael Crowe showed that vector analysis stemmed directly from the quaternions, and attempts were made to restore his name as one of the great scientists, yet it was not enough to counteract the negativity; in the course of the twentieth century Hamilton’s name completely disappeared from the public view.

* Heisenberg’s original paper did not mention Hamilton’s work, that appeared first in a 1925 article about Heisenberg’s theory by Max Born and Pascual Jordan, Zur Quantenmechanik, translated as On Quantum mechanics, and then in the 1926 article Heisenberg wrote with Born and Jordan. Their version became known as ‘matrix mechanics’, that of Schrödinger as ‘wave mechanics’; both versions were later shown to be equivalent.

Still, not only the apparent abstrusity of Hamilton’s work added to his name sinking into oblivion, it was enhanced by the fact that his mathematical-physical-astronomical legacy combined two aspects, each of which by itself overshadowed the general view on his work. One is that he was a generalist, almost to the extreme, which means that he hardly gave examples for his readers to work with and to learn from. The other, that he made his discoveries in what during a large part of the twentieth century were separate fields of science, which means that people tended to choose the discovery in their own discipline as the most important one, and his work was hardly judged in its entirety. That was already noticed in 1866, a year after Hamilton’s death, when Charles Pritchard* wrote in his éloge, “It is as yet premature to anticipate on which of his investigations or discoveries Hamilton’s fame will ultimately rest. There are mathematicians among us who in this respect would be inclined to name his Calculus of Quaternions; others would say that none of his writings can overshadow the importance of his Dynamical Theorems.” And to make it even worse, nowadays his quaternions are used by physicists in the form of vector calculus and the nabla operator \(\small \nabla\), and his mechanics with its Hamiltonian is used by mathematicians, for instance in symplectic geometry.

* Hamilton’s eldest son William Edwin attended Pritchard’s London grammar school for a year, but he did not like it very much.

Despite the revaluation of his work, and its still non-decreasing influence, as shown below, it appears that also restoring the view on his private life is necessary to achieve the restoration of his general reputation as one of the great scientists. I certainly hope that I am making a case for such a restoration; that with writing about Hamilton’s “happy and studious” private life, therewith showing him, as he described himself, as “a labour-loving and truth-loving man,” I may inspire someone who feels at home with mathematics, physics and astronomy, with religion, psychology and metaphysics, and with Ireland in the nineteenth century, to write a new biography of Hamilton.

Hamilton’s work and its modern use

Because Hamilton’s work is not discussed further on this website, an overview of its modern use is given here. Hamilton is widely seen as one of the greatest scientists of his time; where one of his major discoveries would have been enough to make him famous, Hamilton made two. And because he was a generalist pur sang, nowadays both discoveries appear in many branches of science, “building bridges”(1) in physics and “weaving together”(2) advances in mathematics. Hamilton believed that his work was “for a future age entirely” but he would have been very surprised to see what that future age looks like; that his quaternions are now used in apparatuses he could not have dreamt of, and that his mechanics is now used to describe both particles and the Universe, spaces he never could have dreamt up.

The good of H is not in what he has done but in the work (not nearly half done) which he makes other people do. But to understand him you should look him up, and go through all kinds of sciences, then you go back to him, and he tells you a wrinkle.

— James Clerk Maxwell

In 1871 to his friend Peter Guthrie Tait, in connection to Tait’s application of Hamilton’s varying action to brachistochrones.

A call for information

I would like to add more disciplines in which Hamilton’s work is used, such as quantum field theory, number theory, robotics, numerical analysis, structural biology, medical physics, Lie theory, biomechanics, Riemannian manifolds, representation theory, biomedical engineering, chemistry, &c, &c. If anyone using Hamilton’s work, including variations and extensions of it, whether or not Hamilton still would have recognised it, with the only requirement that has a traceable historical path back to his work, from Hamiltonian flows to molecular Hamiltonians and geometric algebra, from the hodograph to computational chemistry and bi-quaternions, from the \(\small \nabla\) operator to Hamiltonian Energy and modified loop cosmology, or even non-Hamiltonicity, could provide me with a short overview like the ones below, I would happily add it.

Optics

Hamilton’s first discovery was a new way to describe optics. He entered College on 7 July 1823, seventeen years old, and on 13 December 1824 his paper ‘On Caustics, part I’, was read at the meeting of the Royal Irish Academy. It was communicated by Brinkley, then Royal Astronomer and president of the RIA. The paper was not accepted for publication in the Transactions and referred to a committee. On 20 May 1825 Hamilton sent a paper to Brinkley, then Royal Astronomer at Dunsink, “giving an ‘Account of some investigations applying the principles laid down in my Essay on Caustics to the Theory of Images and of Telescopes’, suggesting an improved construction of Reflecting Telescopes.” Yet “in consequence of the mirror surfaces in reflecting telescopes being no longer circular but parabolical, improvements with regard to the former such as those suggested by Hamilton have ceased to possess practical value.” Which obviously does not change the fact that he had found it.

On 13 June 1825 the comittee reported about the paper ‘On Caustics’ that it was so abstract and general that it was necessary to explain how the formulae and conclusions were obtained. The paper then evolved into Hamilton’s first paper on the Theory of Systems of Rays, which was published in the Transactions in 1828. It is noted there that the paper was read [1]3 December 1824,* acknowledging that it was in fact the same paper, and in a footnote Hamilton comments that he had extended it during the periods of delay of printing the volume.** Three Supplements would follow, the Third Supplement in 1832. It contains the prediction of conical refraction for which he would be knighted.

* The Academy meetings were held on Mondays; the printed 3 December 1824 was on a Friday, hence a printing error; on Monday “13 December 1824 [...] the paper ‘On Caustics’ was read before the Royal Irish Academy. [...] The ‘Theory of Systems of Rays’ was in fact read before the Royal Irish Academy on 23 April 1827, ” indeed again a Monday.

** The footnote was written at the Observatory in June 1827; Hamilton was appointed Royal Astronomer on 16 June 1827, passed his final exams on 19 and 20 June, and received his BA on 10 July. He therefore must have written the footnote while staying with the departing Brinkley at Dunsink Observatory.

Geometrical optics and conical refraction

Mike Jeffrey, who in 2007 co-authored a paper about the long history of Hamilton’s conical refraction, wrote abou conical refraction, “In 1832 Hamilton used mathematics, that strange abstract language of symbols and axioms, to predict something truly absurd, and obviously physical nonsense. Hamilton predicted a singularity, a point where light’s deterministic journey through a simple crystal broke down. In one stroke, the field of singular optics was born and a sensation began that would take 173 years to run its course. Despite prompt experimental confirmation of Hamilton’s beautiful mathematical theory, the phenomenon was long hindered by controversy and misconception. Victorian mathematics contained only the initial sparks of the asymptotic techniques which would be needed to achieve a full understanding. Conical refraction entered amidst a climax in the contest between undulatory and corpuscular theories of light, entwined in the earliest roots of wave asymptotics and singular optics. The modern theory of light has its origins in Christian Huygens’ 1677 wave theory. This theory did not explain diffraction and did not account for polarisation, which favoured the corpuscular theories backed by the intellectual might of Pierre-Simon Laplace and Isaac Newton. Augustin Fresnel reversed this dominance in 1816 when he discovered the wave theories of refraction and diffraction. Describing light rays as the normals to level surfaces of some characteristic function, Hamilton’s formulation of geometrical optics married the wave theory of Fresnel with the ray method of Newton. Hamilton’s prediction continues to stretch the capability of lasers and computers of the modern age, and embodies all of the complexities of multiple-scales and singularities that plague modern science.”(3)

That “even this esoteric piece of Hamilton’s work is continuing to be made use of” is shown for instance in articles about Conical Refraction in Biaxial Crystals and Conical Refraction Optical Tweezers.

Hamiltonian mechanics

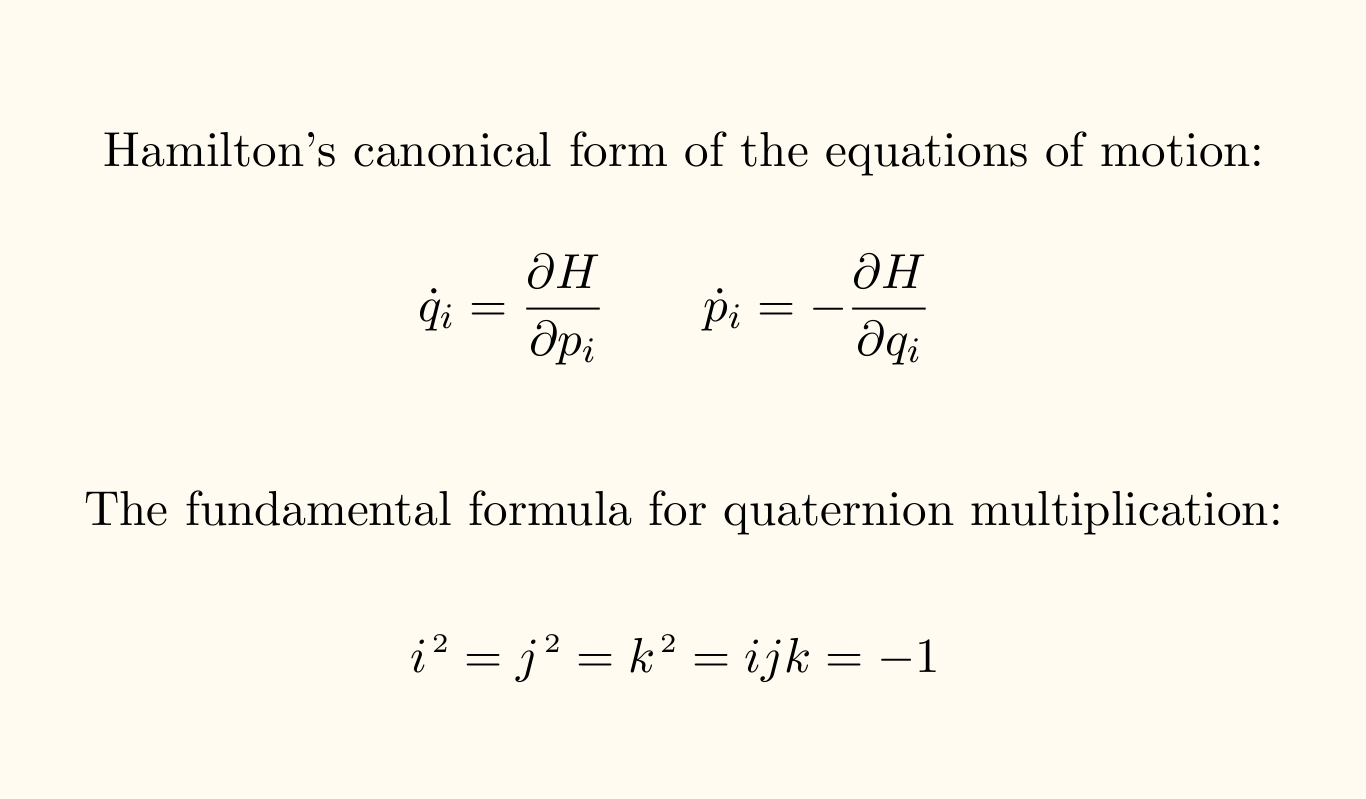

In 1833 Hamilton wrote about his work: “I am still engaged [...] on a work which has already occupied me since I was about eighteen, in attempting, with the help of the differential or fluxional calculus, to remould the geometry of light by establishing one uniform method for the solution of all the problems deduced from the contemplation of one central or characteristic relation.” In Spring 1833 Hamilton “extended from Optics to Dynamics his algebraic method of a characteristic function.” In 1834 and 1835 he further developed his theory, leading to his Second Essay on a General Method in Dynamics, received 29 October 1834, read 15 January 1835. Instead of describing mechanics by the working of forces, as Newton did, Hamilton used the energies of the systems under scrutiny. This mathematically elegant reformulation of classical mechanics is now called Hamiltonian mechanics and, roughly speaking, the energy of a system is called the Hamiltonian.

The Hamiltonian

Terence Tao wrote, “At first glance, the many theories and equations of modern physics exhibit a bewildering diversity: compare for instance classical mechanics to quantum mechanics, non-relativistic physics to relativistic physics, or particle physics to statistical mechanics. However, there are strong unifying themes connecting all of these theories. One of these is the remarkable fact that in all of these theories, the evolution of a physical system over time (as well as the steady states of that system) is largely controlled by a single object, the Hamiltonian of that system, which can often be interpreted as describing the total energy of any given state in that system. Roughly speaking, each physical phenomenon (e.g. electromagnetism, atomic bonding, particles in a potential well, etc.) may correspond to a single Hamiltonian H, while each type of mechanics (classical, quantum, statistical, etc.) corresponds to a different way of using that Hamiltonian to describe a physical system. [... In mathematics,] the Hamiltonians play a major role in dynamical systems, differential equations, Lie group theory, and symplectic geometry. [...] Because of their ubiquitious presence in many areas of physics and mathematics, Hamiltonians are useful for building bridges between seemingly unrelated fields, for instance in connecting classical mechanics to quantum mechanics, or between symplectic mechanics and operator algebras.”(1)

Hamiltonian mechanics in mathematics: symplectic geometry

Fabian Ziltener wrote, “One of the examples of the use of Hamiltonian mechanics in mathematics is symplectic geometry. This is the theory of symplectic structures on manifolds, spaces that locally look like the space we live in but may have any dimension. Describing the state of a classical mechanical system by its generalized position q and generalized momentum p, phase space consists of all such pairs (q,p). In Hamilton’s formalism the motion of a classical mechanical system is governed by Hamilton’s equation, a first order ordinary differential equation for a point in phase space as a function of time. Symplectic geometry has its roots in this reformulation of classical mechanics; in Hamilton’s equation of motion, which is equivalent to Newton’s equations of motion, the standard symplectic structure occurs. Informally, a symplectic structure on a smooth manifold is an assignment that yields a real number for every 2-dimensional subset that is contained in the manifold. Symplectic geometry studies local and global properties of symplectic structures and Hamiltonian systems. A famous conjecture by Vladimir Arnold states that under certain conditions periodic solutions of Hamilton’s equation exist. Physically, such a solution corresponds to a mechanical system that returns to its initial point in phase space after a fixed time.”(4)

Port-Hamiltonian systems in complex physical systems modeling

Arjan van der Schaft wrote, “Hamilton and Lagrange showed that the dynamics of any mechanical system, in the absence of energy dissipation and without interaction with its surroundings, can be formulated as a set of Hamiltonian differential equations. These equations are determined by the Hamiltonian function (total energy) and the symplectic structure on the phase space of the system. Inclusion of energy-dissipating effects (such as damping) and interaction with other systems, results in what is nowadays called a port-Hamiltonian system. ‘Port’ refers to the interconnection channels of the system, similar to the use of the word in electrical circuit theory. Interconnections of simple port-Hamiltonian systems lead to more complex ones. The Hamiltonian of the complex system is the sum of the subsystem Hamiltonians, while its geometric structure is derived from those of its subsystems. This results in a general mathematical framework for the modeling, analysis and control of complex multiphysics systems, as occurring abundantly in the exact and engineering sciences.”(5)

Quaternions

Hamilton’s second major discovery was the extension of the imaginary numbers in such a way that rotations in three dimensions could be described. Because they appeared to have four components instead of three as was expected, Hamilton called them quaternions.* He developed them as pure mathematics, but at the same time he aimed, and succeeded, to use them to solve physics, engineering and astronomical problems. The quaternions had a difficult start, because they ended commutativity in algebra which was not easily accepted.

Fiacre Ó Cairbre wrote, “The mathematical world was shocked at his audacity in creating a system of “numbers” that did not satisfy the usual commutative rule for multiplication. Hamilton has been called the “Liberator of Algebra” because his quaternions smashed the previously accepted convention that a useful algebraic number system should satisfy the rules of ordinary numbers in arithmetic. His quaternions opened up a whole new mathematical landscape in which mathematicians were now free to conceive new algebraic number systems that were not shackled by the rules of ordinary numbers in arithmetic. Hence, we may say that Modern Algebra was born on October 16, 1843 on the banks of the Royal Canal in Dublin.”(6)

But Hamilton’s work was also regularly regarded with disbelief; in 1853 he wrote to a friend, “You will I hope bear with me if I say, that it required a certain capital of scientific reputation, amassed in former years, to make it other than dangerously imprudent to hazard the publication of [the Lectures in Quaternions] which has, although at bottom quite conservative, a highly revolutionary air. It was a part of the ordeal through which I had to pass, an episode in the battle of life, to know that even candid and friendly people secretly, or, as it might happen, openly, censured or ridiculed me, for what appeared to them my monstrous innovations.”

Quaternion algebras

In mathematics, the history of quaternions is a happy one; there they never disappeared from sight.

John Voight wrote, “Quaternion algebras have threaded mathematical history through to the present day, weaving together advances in [many branches of mathematics, and they ...] continue to arise in unexpected ways. [...] Quaternion algebras sit prominently at the intersection of many mathematical subjects. They capture essential features of noncommutative ring theory, number theory, K-theory, group theory, geometric topology, Lie theory, functions of a complex variable, spectral theory of Riemannian manifolds, arithmetic geometry, representation theory, the Langlands program – and the list goes on. Quaternion algebras are especially fruitful to study because they often reflect some of the general aspects of these subjects, while at the same time they remain amenable to concrete argumentation. Moreover, quaternions often encapsulate unique features that are absent from the general theory (even as they provide motivation for it). [...] The enduring role of quaternion algebras as a catalyst for a vast range of mathematical research promises rewards for many years to come.”(2)

For how the efforts of very many people turned Hamilton’s discovery into the contemporary quaternion algebras, see the first chapter of Voight’s Quaternion Algebras.

Quaternions in physics

Another problem was that quaternions live in four dimensions and therefore are hardly visualisable. Hamilton died believing that the quaternions would be at the heart of physics, but about twenty years after his death vector analysis was developed, and because contrary to quaternions vector analysis was very visual, intuitive and easy to work with, in physics the quaternions themselves disappeared for a long time. Only in 1967 vector analysis and the quaternions were reconnected again.

Michael Crowe wrote, “Josiah Willard Gibbs [in] his Elements of Vector Analysis [...] presents what is essentially the modern system of vector analysis.” In 1888 Gibbs wrote to Victor Schlegel that reading Maxwell’s Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism, he concluded that ““although the methods were called quaternionic, the idea of the quaternion was quite foreign to the subject. I saw that there were two important functions (or products) called the vector part & the scalar part of the product, but that the union of the two to form what was called the (whole) product did not advance the theory as an instrument of geom. investigation.” Gibbs then “began to work out ab initio” a new form of vector analysis that involved two distinct products as well as various other features of modern vector analysis. [...] “I saw that the methods wh. I was using, while nearly those of Hamilton, were almost exactly those of

Grassmann.” Gibbs [...] adds: “I am not however conscious that Grassmann’s writings exerted any particular influence on my VA, although I was glad enough in the introductory paragraph to shelter myself behind one or two distinguished names....””(7)

Because therefore vector analysis directly ‘emerged’ from the quaternions it can easily be claimed that, in the form of vectors, the quaternions are at the heart of physics, just as Hamilton had expected. He had an open mind, and doubtlessly would have welcomed this ‘spin-off’ from his quaternions, in which the word ‘vector’ was used in the sense he had given it, and the word ‘scalar’ as he had introduced it.

* The nowadays ‘well-known’ story that Hamilton searched for the quaternions for years on end, and the resulting suggestion that his children asked him about it for years, is not true, and actually, no one even claimed that; it is again a gossipy addition to the sad and alcoholic picture of a distressed Hamilton. In his 1967 A History of Vector Analysis Michael Crowe did not mention how long the children asked about the quaternions, but Hankins wrote in his 1980 biography that Hamilton searched “off and on for the elusive triplets.”

In a letter Hamilton wrote just a month before his death to his son Archibald, he described how he came to his discovery. “I happen to be able to put the finger of memory upon the year and month - October, 1843 - when having recently returned from visits to Cork and Parsonstown, connected with a Meeting of the British Association, the desire to discover the laws of the multiplication referred to regained with me a certain strength and earnestness, which had for years been dormant, but was then on the point of being gratified, and was occasionally talked of with you. Every morning in the early part of the above-cited month, on my coming down to breakfast, your (then) little brother William Edwin, and yourself, used to ask me, “Well, Papa, can you multiply triplets”? Whereto I was always obliged to reply, with a sad shake of the head: “No, I can only add and subtract them.””

The ‘desire’ thus had ‘for years been dormant,’ and Hamilton had travelled to attend meetings until mid-September. From Hamilton’s remark it can be seen that the children asked at breakfast how it went during the first two weeks of October; Hamilton may have started this search late in September. It therefore took him two or at the most three weeks, from late September or the beginning of October until the day of discovery, 16 October 1843.

Applying the Quaternions to engineering in 1850

Physics as we now know it did not exist yet in 1850, as was illustrated above in the state of science in Hamilton’s days. Yet as he had intended, already seven years after he found them, Hamilton used the quaternions to solve an engineering problem. Graves wrote, “In [January 1850] it appears from existing letters that Hamilton was applied to by civil engineers, engaged upon Irish railways, to give the aid of his mathematical knowledge in solving a problem of some practical interest connected with the construction of oblique, or skew, bridges. Hamilton applied to it his method of quaternions, and on the next day supplied the inquirers with an exact solution. A note from Professor [Samuel] Downing, of the Trinity College School of Engineering, ‘returns his sincere thanks to Sir W. Hamilton for his demonstration of that proposition hitherto only approximately solved.’”

Quaternions in spaceflight

The quaternions having been far too complicated to be happily used by humans, after the detrimental vector wars, in physics the quaternions themselves were largely forgotten. Although even the amiable vectors had their opponents; at first, Einstein called Minkowski’s geometrical approach of his relativity theory, published in 1909 and including the then almost brand new vectors, an Überflüssige Gelehrsamkeit.

Yet the coming of computers changed everything. Computers do not care about long calculations, or about intuitivity. And so, in the late 1950s the quaternions re-emerged, apparently at first in 1958, in aircraft simulation, because computers appeared to work with quaternions more easily than with vector analysis and matrix calculus, therewith using less computing power.* After having been used in the Space Shuttle program,** their use in space travel became very widespread.

Noel Hughes wrote, “Vectors and quaternions, along with algebra, trigonometry, geometry, etc. are an intertwined set of tools which can be used to solve many problems that can appear intractable. [Quaternions are used in] spacecraft guidance, navigation and control engineering. [...] Prior to the dawn of the space age and the need for attitude description that does not have singularities, ambiguities, etc., [for most people] quaternions were little more than an esoteric mathematical oddity. [Nowadays] quaternions are used extensively in the Aerospace industry, in the animated film industry and, to a lesser extent, in the medical world. [...] The fundamentals are simple, elegant and straight forward once the superfluous stuff is stripped away.”(8)

Charles Acton wrote about SPICE, an ‘Observation Geometry System for Space Science Missions’ which is completely based on quaternions, “The first “official” use of SPICE was on the Magellan mission, launched in 1989, and it has been used on nearly every worldwide planetary mission since then. For “modern” missions, i.e. everything since Magellan, SPICE is used throughout the mission life-cycle, starting from mission formulation in what NASA calls “Phase A”, through operations (“Phase E”), then in post-mission (“Phase F”) data analysis, and then even for many years thereafter.”(9)

Joe Zender wrote, “Today, for nearly all spacecraft that are sent out into our solar system their attitude is available in quaternions. They are publicly available and distributed by NASA's NAIF Facility. Also most landers’ and rovers’ positional information can be found there. The data covers missions from NASA, The European Space Agency (ESA), The Japanese Space Agency (JAXA), The Russian Space Programme (ROSCOSMOS) and other Agencies. Users are scientists and engineers using software libraries that allows a “rather easy” computation of derived geometric information. One can compute e.g. the answer to the following questions: “At what time will the Mars Express spacecraft come into the field-of-view of the antenna of the Mars Exploration Rover?”, or “Will CASSINI fly through a cometary debris field in year X?”(10)

* Alfred C. Robinson (1928-2015) wrote in his 1958 article, “The general subject of quaternions as applied to coordinate conversions has been under investigation for approximately two years, though the bulk of the work reported here was accomplished during the last six months of 1957.” And in his abstract, “It is shown that the quaternion method is no more sensitive to multiplier errors than is the direction cosine method, and it requires nearly 30 per cent less computing equipment. [...] By every important criterion, the quaternion method is no worse than, and in most cases, better than the direction cosine method.”

The Apollo program

Contrary to what sometimes is claimed, quaternions were not used in the Apollo program. Fortunately, everyone can check the Apollo software now; the Colossus 2A, the Apollo Guidance Computer Command Module software for the Apollo 11 mission on the Internet Archive, and both the Comanche055 and the Luminary099 for the Lunar module of the Apollo 11 mission on GitHub. For computer simulations of the onboard guidance computers used in the Apollo Program’s lunar missions 8, 11, and 17, see The Apollo Guidance Computer.

Added 2025:

There still was a possibility that quaternions were used in the Kalman filter which is used for guidance, navigation and control of for instance spacecraft, or the extended Kalman filter, now the standard in nonlinear state estimation, navigation systems and GPS. But it appeared that in 2010, an article had been published, ‘Applications of Kalman Filtering in Aerospace 1960 to the Present’, from which is it perfectly clear that there were no quaternions in the Apollo Kalman filters. This seems to make it conclusive: there were no quaternions in the Apollo program.

The Gaia mission

Yet, thereafter having been used in the Space Shuttle program, quaternions did not disappear any more, and until March 2025, they were used for instance in the Gaia mission. The satellite was launched in 2013, and ended its science observations in January 2025, and the aim is to create an extraordinarily precise three-dimensional map of stars throughout our Milky Way galaxy and beyond, in order to “tackle an enormous range of important questions related to the origin, structure and evolutionary history of our galaxy.” Quaternions are used in the Gaia satellite for attitude representation.

Anthony Brown wrote, “The goal of the Gaia mission is to create the highest accuracy three dimensional map to date of more than two billion stars in our Milky Way galaxy and beyond by measuring their distances, motions, and astrophysical properties. The distances and motions of stars are determined by repeatedly measuring their positions on the sky (astrometry). The changes over time in these positions contain information on the distances to the stars (through their parallaxes) and their motions through space (via their proper motions).

The Gaia spacecraft consists of two telescopes that observe the sky simultaneously in two directions separated by an angle of \(\small 106.5^\circ\). In order to know at which star a telescope is pointing, the orientation of the Gaia spacecraft in space has to be known. This orientation is determined in the first instance through on-board star trackers, which rely on the know positions of stars from the Hipparcos catalogue. This provides the attitude of the spacecraft, sent down with the telemetry in the form of quaternions, to a precision of the order of a few arcseconds. However, Gaia aims to measure star positions to an accuracy of a few micro-arcseconds which means that the attitude of the spacecraft most be know to a much higher precision also, of the order of a few tens of micro-arcseconds.

This high precision is obtained by including the attitude as part of the calibration terms of the astrometric solution for Gaia. This means that the same measurements are used to determine the star positions, parallaxes, and proper motion, and the high precision version of the spacecraft attitude. This is done in an iterative process which is summarized in this review.

Mathematically the attitude in the astrometric solution is represented by quaternions which describe the orientation of the spacecraft as a function of time. The technical implementation is to use B-Splines to model the quaternion coefficients as a function of time.”(11)

Quaternions in animation

In 1985 the apparently earliest article introducing quaternions to computer graphics was published.

Ken Shoemake wrote, “Solid bodies roll and tumble through space. In computer animation, so do cameras. The rotations of these objects are best described using a four coordinate system, quaternions, as is shown in this paper.”(12)

Thereafter the quaternions in this field have been developed almost beyond recognition.

Manos Kamarianakis and George Papagiannakis write in their 2020 article, “Skinned model animation has become an increasingly important research area of Computer Graphics, especially due to the huge technological advancements in the field of Virtual Reality and computer games. The original animation techniques, based on matrices for translation, rotation and dilation, are still applied as the latest GPUs allow for fast parallel matrix operations. The fact that the interpolation result of two rotation matrices does not result in a rotation matrix, forced the use of quaternions as an intermediate step. The extra transmutation steps from matrix to quaternions and vice versa, adds some extra performance to the animation but yields better results, solving problems such as the gimbal lock. Nowadays, the state-of-the-art methods for skinned model animation use dual-quaternions, an algebraic extension of quaternions. [...] Dual-quaternions handle both rotations and translations, but cannot handle dilations. [...] Conformal Geometric Algebra (CGA) is an algebraic extension of dual-quaternions, where all entities such as vertices, spheres, planes as well as rotations, translations and dilation are uniformly expressed as multivectors. The usage of multivectors allows model animation without the need to constantly transmute between matrices and (dual) quaternions, enabling dilation to be properly applied with translation.”(13)

Astronomy

A special place is for astronomy because it pervaded all Hamilton’s work. In 1827, when Hamilton was still very young, he described his passion for mathematics to William Wordsworth (1770-1850), showing how it was always entwined with his love for astronomy and his deep religious feelings. “Science, as well as Poetry, has its own enthusiasm, and holds its own communion with the sublimity and beauty of the Universe. And in devoting myself to its pursuits, I seem to myself to listen [...] to the promise of a [pure and noble] reward, in that inward and tranquil delight which cannot but attend a life occupied in the study of Truth and of Nature, and in unfolding to myself and to other men the external works of God, and the magnificent simplicity of Creation.”

Hamilton indeed always related his work to Nature and the Universe. To give some examples; in 1833, having extended his mathematical methods from optics to dynamics, he wrote to his friend Aubrey de Vere that he had been drawing up, for the Dublin University Review a sketch of his ‘general method for the paths of light and of the planets’; in 1848 he discussed his optics with Lord Rosse, who had built the then largest telescope in the world. He applied his Calculus of Quaternions to the theory of the Moon, and in both books, the Lectures (1853) and Elements (1866) to celestial mechanics, in the Lectures even stating that he preferred to take his “illustrations from Astronomy.” He also wrote for the general public; in 1833 he wrote for the Dublin Penny Journal about the comet Biela, and in 1850 he sent a report to the Dublin Saunders’s Newsletter about a marvellous meteor he had witnessed; the first known report of a member of the Scorpiid-Sagittariid Complex.

Astrophysics

Andrew Hamilton (no relation to Sir WRH) wrote, “Astrophysicists, who harness mathematics and physics to study astronomical phenomena, use Hamilton's work every day all the time. Hamiltonians are at the core of the two pillars of modern physics, general relativity and quantum field theory. Hamiltonian dynamics is central for understanding the dynamics of gravitating systems such as solar systems and galaxies, or the dynamics of electrodynamic systems such as plasmas. Hamilton's quaternions are by far the most powerful and elegant way to understand and encode spatial rotations, and his biquaternions, having complex numbers as their coefficients, do the same thing for spacetime rotations, also called Lorentz transformations. Hamilton's impact on theoretical astrophysics is everywhere.”(14)

An additional discovery, the Hodograph

In November 1846, while giving a course of astronomical lectures in Trinity College Dublin, Hamilton invented the hodograph. Graves wrote in his biography, “The course of lectures delivered by Hamilton [...] had for its chief subject the perturbation of the planetary orbits, in connexion with the recent discovery of the ultra-Uranian planet, which had not yet definitively received the name of Neptune. It is to the direction thus given to his thoughts that we probably owe an astronomico-mathematical discovery of remarkable elegance [...]. It was communicated by him to the Royal Irish Academy on the 14th December, 1846.” In the Contents on p. viii, the communication was called ‘A new Method of expressing, in symbolical Language, the Newtonian Law of Attraction, &c.’, and it was, in 1847, followed by two further communications.

In the communication, Hamilton wrote that it was ‘a new mode of geometrically conceiving, and of expressing in symbolical language, the Newtonian law of attraction, and the mathematical problem of determining the orbits and perturbations of bodies which are governed in their motions by that law. Whatever may be the complication of the accelerating forces which act on any moving body, regarded as a moving point, and, therefore, however complex may be its orbit, we may always imagine a succession of straight lines, or vectors, to be drawn from some one point, as from a common origin, in such a manner as to represent, by their directions and lengths, the varying directions and degrees (or quantities) of the velocity of the moving point: and the curve which is the locus of the ends of the straight lines so drawn may be called the hodograph of the body, or of its motion, by a combination of the two Greek words, ὁδός, a way, and γράφω, to write or describe; because the vector of this hodograph, which may also be said to be the vector of velocity of the body, and which is always parallel to the tangent at the corresponding point of the orbit, marks out or indicates at once the direction of the momentary path or way in which the body is moving, and the rapidity with which the body, at that moment, is moving in that path or way.”

Graves remarked, “It was shown by Hamilton that in all cases where the Newtonian law of the inverse square holds good (the force being supposed to act towards a fixed centre), this locus is a circle, and reciprocally that no other force would conduct to the same result – that the Newtonian law of attraction may be characterised as being the law of the Circular Hodograph.”

In his 1853 Lectures on Quaternions, Hamilton wrote, “I am anxious to acknowledge here, that in the general conception of connecting by some curve or line (by me called as above the hodograph) the terminations of lines drawn from one common point to represent the varying velocities of a body, I have found myself anticipated by Moebius, who has introduced that conception (but not, so far as I have noticed, the theorems above referred to), in his clear and valuable book on the elements of physical astronomy, entitled "Mechanik des Himmels" (Leipzig, 1843).

Explaining his discovery to his friend Maria Edgeworth, Hamilton wrote, “Kepler discovered the elliptic orbit; I venture to propose the consideration of another curve, which I have called the circular hodograph.”

Before Hamilton’s discovery of the quaternions in 1843, vectors were not used yet as arrows showing direction and signifying magnitude by their lengths,* and the hodograph being a vector diagram, it was one of the earliest applications of the quaternions. The hodograph is now used in “many different branches” of physics, particularly in astronomy, solid and fluid mechanics, and meteorology.

* Having found the quaternions in 1843, Hamilton called the real part of a quaternion the scalar part, and the imaginary part the vector part, and the pure quaternion, having a zero scalar part, is nearly what is now called a vector. The word vector was not new, but the so-called ‘radius vector’ had only been defined as having length. In 1844 Hermann Grassmann published Die lineale Ausdehnungslehre in which he developed a ‘general calculus of vectors’. Hamilton read it in January and February 1853.

The hodograph and the motion of a particle

In 1867, Tait gave in his Note on the Hodograph some examples of “how easily the geometrical ideas supplied by Hamilton’s beautiful invention of the Hodograph enable us to dispense with analytical processes in the establishment of some of the fundamental propositions connected with the motion of a single particle [...]; and also how they help us to understand the full bearing of some of the analytical methods.” In 1873 Maxwell, in the second volume of his 1873 Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism, elaborated on Tait’s sixth example: how to use the hodograph for finding the acceleration of a particle which describes a logarithmic spiral with uniform angular velocity about the pole.

The hodograph and meteorology

As pilot balloon hodographs already having been used in meteorology in 1929, at Little America, nowadays hodographs are used to plot the trajectory of an air parcel as it ascends through the troposphere. The hodograph is based on wind vectors which indicate speed by their lengths, and it is used to reveal vertical wind shear, a change over a short distance in either wind speed or direction, or both. In a hodograph, the vertical wind shear is determined by taking the vector difference between the horizontal winds at two levels of height.

Jacob Kuiper wrote, “In meteorology, the hodograph is regularly used when considering expansion or contraction, as well as changes of speed and direction, of the wind between the earth’s surface and that at higher altitudes. From the patterns of wind speed factors at various heights, a hodograph can be constructed. That may yield many indications as to the probability of the forming of very heavy types of showers and whether, for example, they could lead to tornadoes.”(15)

References

(1) Terence Tao (2008), Hamiltonians.

(2) John Voight (2020), Quaternion algebras.

(3) Mike Jeffrey (2021), slightly adapted from Hamilton’s Diabolical Legacy, and personal communication. See for a history and explanation of conical refraction Berry and Jeffrey 2007.

(4) Fabian Ziltener (2017), Summer School Symplectic Geometry, personal communication.

(5) Arjan van der Schaft (2021), Port-Hamiltonian Systems: An Introductory Overview, personal communication.

(6) Fiacre Ó Cairbre (2010), Twenty Years of the Hamilton Walk.

(7) Michael J. Crowe (1967), A History of Vector Analysis, and the history of the book (2002).

(8) Noel Hughes (2021), Researchgate comments and personal communication.

(9) Charles Acton (2021), personal communication.

(10) Joe Zender (2021), personal communication.

(11) Anthony Brown (2025), personal communication.

(12) Ken Shoemake (1985), Animating rotation with quaternion curves.

(13) Manos N. Kamarianakis, George Papagiannakis (2020), Deform, Cut and Tear a skinned model using Conformal Geometric Algebra.

(14) Andrew J.S. Hamilton (2021), personal communication.

(15) Jacob Kuiper (2023), personal communication.

A Victorian Marriage : Sir William Rowan Hamilton (502 pages) - an overview

In 2017 I published (a corrected version of) my first book, or actually a history essay because it is written as a ‘defense,’ A Victorian Marriage : Sir William Rowan Hamilton, in which I showed that the unhappy and alcoholic view on Hamilton is flawed, and how this idea emerged, unintentionally, from the enormous biography about Hamilton, written by Robert Perceval Graves and published deep within the Victorian era, vol 1 (1882), vol 2 (1885), vol 3 (1889). Reading the biography in the context of his time, a picture emerged of a man who did not just use his enormous intelligence for his work, but also for his private life. A genius in a happy marriage, with ups and downs as we all have.

The first seven chapters, Introduction, Early years, A lover, A brother, A husband, A good marriage, and Later years, are a description of Hamilton’s private life. In 1824, only nineteen years old, Hamilton fell in love with Catherine Disney. After some months of unspoken love she married someone else, and it took him six years to cope with his loss. In 1831 he fell in love with Ellen de Vere, who did not love him back, causing months of very melancholy feelings. Then, in the summer of 1832, Hamilton made a remarkable discovery; he saw that he was wasting his life on passion, and found a way to change his behaviour. His zest for life was restored, and he fell in love with Helen Bayly.

Indeed, contrarily to what has been suggested, that Hamilton always remained to love only Catherine and hence had an unhappy marriage, it is clear from a letter to a friend that he really had been in love with Ellen de Vere, writing that he had had “another affliction of the same kind and indeed of the same degree” as his love for Catherine had been. And having sent his ante-nuptial poems about Helen Bayly to Coleridge, believing that poems had to come from true feelings and highly admiring Coleridge, may serve as one of the ‘proofs’, if these are needed, that he indeed was very much in love with her. The chapters end with Hamilton’s later years and death.

Chapter 8, A lost love, is about what happened with his first love Catherine Disney. It is shown that at the time of her marriage, in 1825, Hamilton had not known that Catherine had been forced to marry someone she did not love. Having been told that she was going to marry he had not seen her again; he saw her only in 1830, 1845, and in 1853 shortly before she died. Hamilton had assumed that Catherine had wanted to marry until, in 1830, he visited her, and saw that she was unhappy. About the 1845 visit nothing further is known, but in 1848 she told him in a correspondence that her marriage had been unhappy from the start. Only in 1853, some weeks before her death, she could finally tell him that she was coerced into this marriage, and that she had wanted to marry him. Each time Hamilton again learned about new details, and about how terribly unhappy Catherine was, he was understandably distressed. Which is entirely different from having loved only her his whole life.

The 9th chapter, Solemn dogged seriousness, is a description of the Hamiltons at home, as far as it could be extracted from the biography; although they had their ups and downs, as everyone has, they had a good and happy marriage. Familiar traits are discussed, and anecdotes given, as told by the eldest son, William Edwin, after his father’s death. One of these anecdotes became the direct origin of a part of the contemporary gossip; the view on Hamilton as a very disorderly man, which led to the conclusion that Lady Hamilton thus was a bad housewife, from which it was concluded that their marriage was unhappy, and that Hamilton started to drink alcohol because she did not serve dinner. Which clearly was not the case as could already have been concluded from the anecdote itself. This chapter also contains a discussion of their illnesses, Hamilton’s gout and Lady Hamilton’s weak health. Very likely reasons are given for Lady Hamilton’s two nervous breakdowns, which directly had to do with her marriage; being a married woman in Victorian times was indeed extremely difficult. Yet both times the Hamiltons were able to solve their problems.

The 10th chapter, An occasional mastery, is about Hamilton’s alleged alcoholism. It is discussed what exactly happened, and that what Graves called “an occasional mastery”, hinting at it long before describing it while vaguely predicting doom to come, was a one-time event in 1846. It is also discussed how especially in Hamilton’s so-called ‘High Church days,’ which lasted from about 1839 until late in 1845 or very early in 1846, it was extremely unlikely that he was drinking too much. And indeed, Graves never claimed that Hamilton was an alcoholic.

In the first part of the 11th and last chapter, By no means an alcoholic, Hamilton’s use of alcohol is discussed based on the DSM-5, using the information found in Graves’ biography. The conclusion was that Hamilton did not meet the DSM-5 conditions for alcoholism and that, had he lived now, he thus would not be regarded as alcoholic.

Having shown that Hamilton was not an alcoholic, it was considered how much risk there had been that he would have become one. To that aim the data from Graves’ biography about when and how much alcohol Hamilton drank are used, in a worst case scenario, to fill in the AUDIT test which can be found on p. 17 of the manual published by the World Health Organization. It is designed to test what the risks are for someone, in this case Hamilton, to become an alcoholic. The overall conclusion was that, in this worst case scenario, during two periods of his life Hamilton would have had an increasing risk of becoming alcoholic, but that he never reached the higher risk levels of becoming one.

During these two periods of increasing risk Hamilton, who always remained temperate at home, sometimes drank much in public. The first period started in 1844 when after having discovered the quaternions Hamilton seemed to become overworked, and ended in 1846, with the event at the Geological Society. Thereafter Hamilton was warned by Charles Graves, brother of the biographer Graves and fellow mathematician at Trinity College Dublin, that he was ruining his Dublin reputation; Hamilton immediately changed his behaviour and became abstemious for two years. The second period started in the summer of 1848 and ended when, most likely in 1851, but in any case before the end of 1853, Hamilton was again warned by Charles Graves. Drinking wine, and sometimes much, at dinners and parties had been completely accepted until around 1840 the Temperance Movement had reached Dublin, and apparently the gossip about Hamilton’s drinking was worsening again. This second time he changed his behaviour less rigorously but lasting; although he did not abstain again, he never drank much any more.

It then is discussed briefly where Graves’ information about Hamilton’s private life came from; Graves lived in England from 1833 until 1864, thus from the time Hamilton married until one year before he died. Apart from writing letters other means of contact did not exist yet, and they did not visit each other frequently, apparently not even yearly, which means that Graves hardly saw Hamilton live his daily life. The essay is concluded by a revaluation of the two main biographies, written by Graves in the 1880s and by Thomas Hankins in 1980. It is shown that all the information these two biographies contain can be placed in a much more positive light than is done nowadays, by putting Hamilton’s life in the context of his time, and carefully noticing all the nuances Graves gave in his biography.