Background information

Utrecht, 15 October 2025

—

The Hamiltons of Jervis street, and Archibald Hamilton’s amazing career

One of my very early unpublications was The Hamiltons of Jervis street. I wrote it in early 2018, when my ideas about what Hamilton’s private life had looked like had fully matured, obviously within the boundaries of what can be known, but Graves’ biography still contained myriads of details I had not seen or noticed yet. Details which appeared interesting enough to elaborate on, or details which due to the gossip changed beyond recognition and were in dire need of restoration, and I am certain even now there still are by me unnoticed details which are worth investigating.

In the Jervis street unpublication I introduced Hamilton’s eldest paternal uncle, Arthur Rowan Hamilton, of whom I found, by comparing church records with remarks made by Graves in his biography, that he must have been the uncle who “died in a French prison.” That was something Graves mentioned but never wrote anything else about; he may only have heard about it after Hamilton’s death, when he was doing his research for the biography.

Because of the combination of Arthur Rowan Hamilton having died in a French prison, Archibald Hamilton Rowan having escaped to France, and Arthur’s mother Grace Hamilton née McFerrand and Archibald’s mother Jane Hamilton née Rowan having fallen out with each other, I had made the suggestion that these events somehow had been connected, that perhaps Arthur Rowan had come to France with Archibald Hamilton Rowan, and that Grace blamed him for her son’s death, therewith falling out with the Hamiltons of Killyleagh. But then I found that Jane had died in 1793,* and Archibald Hamilton Rowan’s escape was in 1794, therefore, such a direct connection was impossible.

* I had found in Archibald Hamilton Rowan’s autobiography, that Jane Rowan had died in early 1793, and then it was easy to find her burial record. She died in Dominick street, where Hamilton Rowan had his house on no. 1, and she was buried on 22 February 1793. Apparently, also her mother Elizabeth Rowan née Eyre had lived in Dominick street; she died 23 January 1775, and was buried, as “Mrs. Roan”, on 27 January 1775 in the vault of St. Mary’s, where later also her grandson Archibald Hamilton Rowan would be buried.

The first part of 2025, I had been immersed in the story of one of Hamilton’s French relatives, a daughter of a first cousin of Hamilton’s great-grandfather Philbert Guinin. The cousin was Elizabeth Givry, who was born in Stenay, and baptised 12 May 1732; her daugher was Gabrielle Joséphine de la Fitte de Pelleport, who was also born in Stenay, and in her teens walked around in the Versailles Palace of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette until in 1789 the revolution broke out. Many years later she wrote her memoirs, which I very unexpectedly found when I searched if anything was known about the Givry family of Stenay. I only planned to translate the first chapter of her French Souvenirs, because it told the story of her mother Elizabeth Givry, but my plans to stop there were overruled by my fascination to read about the French revolution from so close-by, and from a purely personal point of view.

But by sheer coincidence finding when, after his escape from Dublin, Archibald Hamilton Rowan arrived in Paris, I decided to first rewrite my 2018 unpublication. The coincidence was that in his autobiography, Archibald Hamilton Rowan had mentioned that before arriving in Paris he had seen the Festival of the Supreme Being in Orléans, and working on Gabrielle Joséphine’s memoirs, I knew that for a short time late in 1793, around the time of the Festival of Reason, Gabrielle Joséphine had left the village she then lived in because the villagers had thought it a good idea to carry her around in procession, as the personification of the Goddess of Reason. To understand wat this was about, I had read about the ‘Cult of Reason’ and its successor, the ‘Cult of the Supreme Being’, and about the course of the revolution. Now knowing that the ‘Festival of the Supreme Being’ was held on 8 June 1794, I also knew when Archibald Hamilton Rowan had arrived in Paris, and that my suggestion could not be true because Jane Rowan had died before Archibald Hamilton Rowan escaped to France. Unfortunately, finishing Gabrielle Joséphine’s memoirs now had to wait a bit.

While rewriting, taking out the suggestion that Archibald Hamilton Rowan’s escape had to do something with Arthur Rowan Hamilton dying in a French prison, and trying to gain an idea of what could have led to the death of Arthur Rowan, I found as possibilities the War of the First Coalition, or the Irish Brigade in France; the latter entailed a surprise. Some time ago, I had found, in the King’s Inns papers, that Archibald Hamilton, Hamilton’s father and Arthur Rowan’s younger brother, had been apprenticed to an attorney in 1791 already, but I had considered writing a separate article about him and his amazing career. But 1791 also having been the year that ‘uncle James’ of Trim, brother of both Arthur Rowan and Archibald, had entered College, I now saw that it also was the year the Irish Brigade had been disbanded. Therefore, I suggested a possible connection between these three events. I have no idea how close, or far away it is from the truth, but my hope is that someone will recognise something, and contact me. It would in any case explain the strangeness of Arthur Rowan Hamilton’s name not being found on the internet; in 1791 he was only 16, which makes it possible that no one had written anything about him yet.

Then, as things go, realising that the Hamiltons of Jervis street were most likely Presbyterians, that Hamilton’s parents were members of a nearly “dissenter” congregation, and finding that in 1796 Archibald entered as attorney Exchequer, it became very likely that Archibald had been apprenticed to Robert Hutton, who was from a largely ‘dissenter’ family, was an attorney Exchequer and the father of Sarah Hutton, whom Archibald married in 1800. And then even Letitia Webber, the mother of Daniel Webb Webber who had shown that Hamilton was related to Lord Adare, and who was a sister-in-law of Hamilton’s grandmother Mary Anne Guinin, entered the story, albeit just in a footnote. That is also something I am not certain about, but it seemed interesting and at least possible.

Last but not least, the unpublication had become the perfect place to finally discuss the career of Hamilton’s father Archibald Hamilton. I had known about it for some time already because I had been searching the Dublin Directories when I stumbled on Hamilton’s French family, and had become distracted. From the almanacks it is very obvious that Archibald indeed had an amazing career, as Hamilton had alluded to in 1852 when he wrote, “he must have been in the very first rank of Dublin solicitors”. Archibald Hamilton died when he was only 41, yet he had already become a Member of the Law Club, and had entered the Nobility and Gentry section of the Dublin Directory or Treble Almanack.

The unpublication now also became the natural place to write about Archibald Hamilton’s 1807 bankruptcy, and why it was “concluded” that it had to do something with the reason Hamilton was sent to Trim, that it had been due to financially difficult circumstances. That had only been an inconsiderate suggestion made by Hankins, Hamilton’s 1980 biographer,* and had been accompanied by Hankins’ erroneous assumption that all children had been sent away at the time of the bankruptcy. Graves had been absolutely clear that that was not the case, and that also appears from letters written at that time, mainly by aunt Sydney Hamilton, the sister of Arthur Rowan, James and Archibald. Yet unfortunately, Hankins’ suggestion had already become the accepted truth.

* Unfortunately, Hankins’ 1980 biography is not open access available online.

And then, when I was thinking about finishing Gabrielle Josephine’s memoirs, the scans of these early letters arrived, provided by Trinity College Dublin Library, and to wrap up the story about how Hamilton went to Trim and how it indeed had absolutely nothing to do with financial circumstances, I now will annotate them, and discuss a very common custom which has been completely forgotten nowadays, but which with hardly any doubt was the reason Hamilton’s education had to wait until he was three years old.

Utrecht, 28 October 2024

—

The Plaque and The Walk on 16 October 2024

All uncredited photos were made by Eli Sarkol.

The unveiling of a plaque at (the place of) Hamilton’s childhood home.

Some time ago Finbarr Connolly, Miguel DeArce and I applied for a new plaque for Sir William Rowan Hamilton in Lower Dominick Street because the previous one had disappeared at the time of the last renovation of Hamilton’s birth house. To my happiness, also Colm Mulcahy, Anthony O’Farrell and Iggy McGovern joined in. The Dublin City Council’s Commemorative Plaques Committee soon gave her approval, and after announcements, on 16 October 2024 the plaque was unveiled by Deputy Lord Mayor Cllr Donna Cooney. I was very happy that in the announcement, instead of calling the site ‘Hamilton’s birthplace’ as we all had done before, Brendan Teeling called it the site of his ‘childhood home’, as Hamilton indeed saw it.

There were four short speeches; the first by DLM Donna Cooney. Her text is in the news item of the Irish Independent which was published online that same day. I was the second, and having been quite stressed about reading aloud in English, DLM Cooney made me feel at ease, for which I thank her. This was my text, with which I aimed to paint a picture of Hamilton as a child in this street, and in the house which stood on these very same foundations. Then Peter Gallagher spoke about Hamilton’s work and Dunsink, and finally Iggy McGovern read a poem from his sonnet-sequence about Hamilton, called Geometry, about Hamilton having been A RUGADH ANSEO.

The unveiling of the plaque. After DLM Donna Cooney, I gave a short speech.

DLM Donna Cooney spoke first, Peter Gallagher third, then Iggy McGovern.

The plaque was unveiled on 16 October, the day Hamilton found the quaternions.

It was unveiled at the site of Hamilton’s childhood home in Lower Dominick Street.

For the last photo, we were joined by Tony O’Farrell, Leo Creedon and Eoin Gill. Unfortunately, Iggy McGovern had to leave early.

Tony O’Farrell, Leo Creedon, Anne van Weerden, DLM Donna Cooney, Peter Gallagher, Eoin Gill.

And even though in these photos the group of people standing on the side walk cannot be seen, yet amongst them were Rod and Glen Smith of New Zealand, who are related to Brabazon Barlow, Catherine Disney’s fourth son. And later that day, at Dunsink, we also met Hilary Thompson, who now lives in one of the houses where Catherine Disney once lived. For these remarkable encounters, see the blog of 2 November 2024 on my Catherine Disney page.

A tablet and a brick

At some time after the ceremony someone told me something remarkable, which needs some introduction. As mentioned earlier, the renovations of Hamilton’s childhood home had been executed in two different stages. In the first, the upper three storeys had been demolished and replaced by four storeys, only leaving the original front of the lowest storey of the house, yet it still held the previous plaque, or tablet. In the second stage, executed at some time before 2009, that last original piece of the house was renovated, and thereafter the tablet was gone. Some years later, the tablet had been brought to Dunsink, but I never heard details about that.

What was remarkable was that apparently, on the day before the unveiling, someone had cycled to Dunsink to give them one of the original bricks of the house, which probably also was collected during the last renovation. Now both the first tablet, and an original brick of Hamilton’s childhood home are at Dunsink; what a treasure.

Because my quest is to correct as many flaws in Hamilton’s story as possible, I have to make some remarks about the speech as given in the Irish Independent.

The first is, that Hamilton never really contemplated becoming a poet in the sense of not being a mathematician any more; in 1825 he wrote to his friend Arabella Lawrence, “There is little danger of [poetry] ever usurping an undue influence over a mind that has once felt the fascination of Science. The pleasure of intense thought is so great, the exercise of mind afforded by mathematical research so delightful, that, having once fully known, it is scarce possible ever to resign it.” Moreover, he had said the same about both poetry and the Classics; that if he could have reached their summits he would have tried, but mathematics was his power. And that was also what Wordsworth said; poetry always requires very intense labour, so do not stoop for poetry if you can reach the summit in mathematics.

The second is that there was an unfortunate mixup between Hamilton’s father Archibald Hamilton (1778-1819) and Archibald Hamilton Rowan (1751–1834). It was Archibald Hamilton Rowan who had ‘rubbed shoulders with Wolfe Tone,’ and he had been in Philadelphia in 1795, when Hamilton’s father Archibald was only 17. There was a connection between them, but that is a long and intricate story, and it was not one of bloodlines. At the moment (2024) I am working on an article about Hamilton’s father Archibald, but it will need a lot of time. Fortunately, searching for historical facts and records becomes easier by the year because of the many ongoing digitalisation projects.

The third is that, however important quaternions now are for space travel, for instance being used for attitude determination and control, they were not necessary for going to the moon; the Apollo project was done without them. Having searched the Apollo codes which are online, for instance at the IA, at Github, and at Ibiblio, we did not find any quaternion, and I never heard that someone else did find one. Obviously, next to matrices, also vectors were used for guidance, navigation and control, and vector analysis being a spin-off of the quaternions, extensions of Hamilton’s work on quaternions were used. But it goes too far to say that Hamilton “would later help to put men on the moon.” Yet, as always, if anyone can show there were quaternions in the Apollo program after all, please contact me, I would be very happy to know.

Not in any way erroneous but just something to contemplate on, is that Hamilton refused to become godfather of Oscar Wilde. I have often thought that, had Hamilton known that Oscar Wilde had been born on 16 October 1854, ie., on Quaternion day, he perhaps would have considered becoming his godfather, dates were important for him. Born at midnight on 3/4 August, his birthday had always been celebrated on the 3rd, but when his son Archibald was born on 4 August 1835 he changed his own birthday to the 4th also. And in May 1838 he wrote to Adare, that when his eldest son William Edwin had become four years old on the 10th of May, “it happened curiously that his younger brother, Archibald Henry, was exactly a thousand days old.”

Yet it is very likely that Hamilton did not know when Oscar was born; he was only baptised on 26 April 1855, when he was six months old already. On 4 May 1855, eight days after Oscar’s baptism, Hamilton wrote to De Morgan that the first time he had seen Mrs. Wilde had been at a party, where she had told him about her “young pagan,” that he then did not know the sex of the baby, and that she asked him to become godfather. That “Saturday last,” ie., 28 April 1855, Mrs. Wilde visited the Observatory, and that she told him about the baptism, which had happened on the “previous day,” but actually on the day before that.

A likely reason to refuse is that Mrs. Wilde called her baby her “young pagan”; it is doubtful that the deeply religious Hamilton would have been at ease with being associated with that, however much he liked and admired her. Interestingly, Hamilton wrote about four names for Oscar, yet the record gives three names. Apparently, the name Wills was added later, which means it is unknown what the original fourth name was. Perhaps Mrs. Wilde had not seen the written record, and did not know there were only three names in it.

And the last one is that the Hamilton Lunar Crater is certainly true!

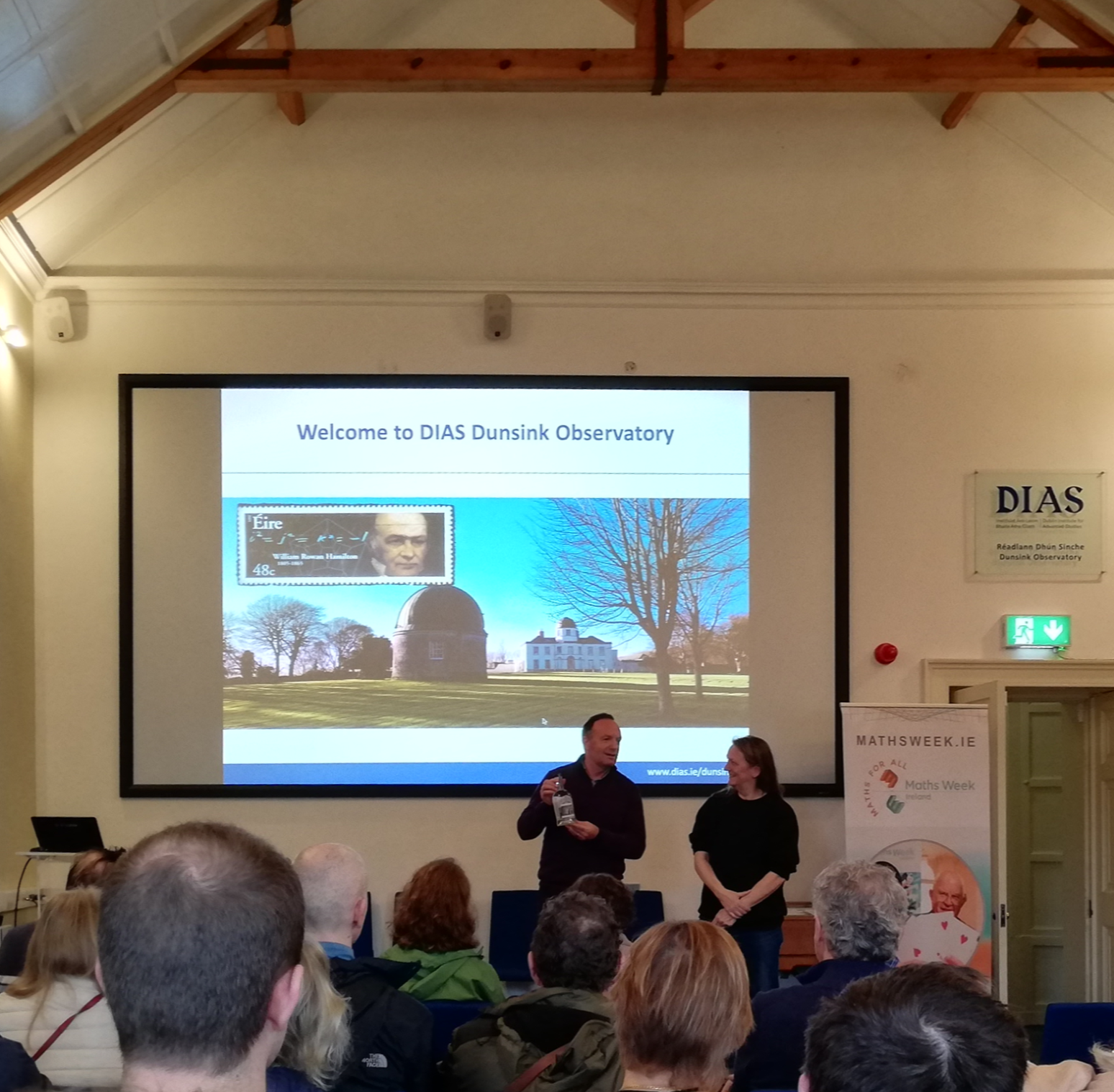

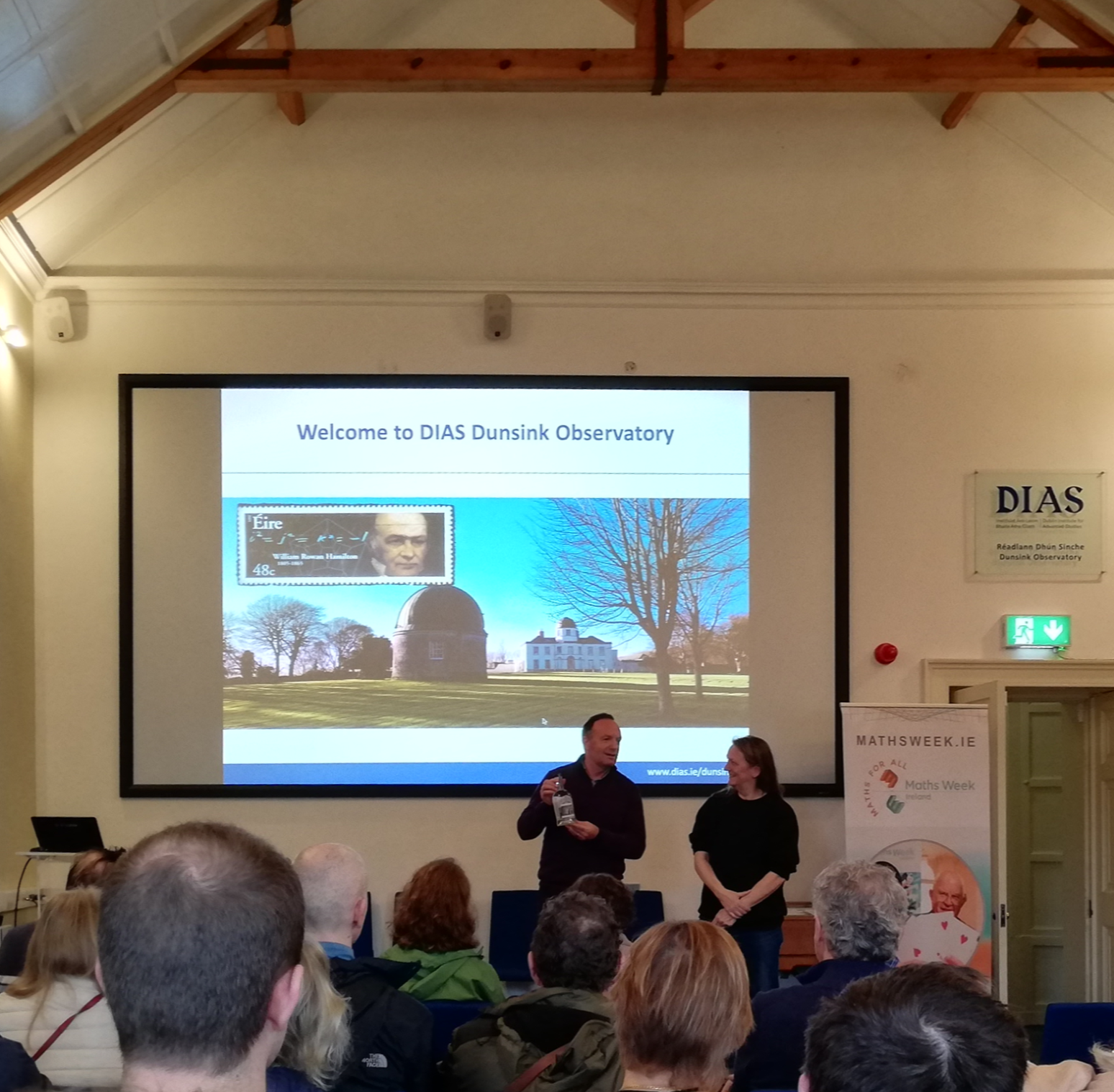

The 2024 Hamilton Walk

The plaque having been unveiled, Eli and I went, together with Leo Creedon,* from Dominick street to Broom Bridge by tram, then to Navan Park Road by train, and then we walked to Dunsink Observatory. Fortunately, we were just in time for the yearly introduction to the Walk by Fiacre Ó Cairbre in the meridian room of Dunsink. Then, something unexpected happened there. To my utter surprise, Peter Gallagher called me to the podium “to embarrass me” 🙃, and because I had been “correcting our history,” I received a bottle of original Gallagher ‘Hamilton Gin’. In 2019, when she showed us the ‘Hamilton room’, Hilary O’Donnell of Dunsink had told us about it, but I never had imagined I once would possess a bottle!

Receiving a bottle of Hamilton Gin in the Meridian room of Dunsink.

* During the walk to the observatory, Leo Creedon told us that it was not Hamilton, but Robert Murphy (1806-1843) who was the first to have found non-commutative algebra, while working on functions. Unfortunately, Creedon’s Masters thesis is not available online. He also told us that when he was doing his research on Murphy, he was as eager to talk about Murphy as I am about Hamilton. Having read Murphy’s obituary, which was written by Hamilton’s friend Augustus De Morgan (1806-1871), and is quite a sad one, I am curious whether Leo Creedon agreed with this version of Murphy’s private life.

As a funny coincidence, the bottle solved a for me long-standing mystery. I had wondered why, at ResearchGate, when there still were projects, my Alice article had been tagged with ‘Sorbus’ and ‘Rosaceae’. Now looking at the the label of the bottle, it said, ‘Irish gin infused with Rowan Berries’. I had never heard of Rowan Berries, and looking it up, it appeared that they are of the genus Sorbus of the family Rosaceae!

Getting ready to start the Walk, I told Peter Gallagher that in 2019 we could not see the second floor of Dunsink because someone was living there, and I asked if he, some day, perhaps could make a short video or something, because I was very curious what it looked like upstairs. To my amazement, he offered to show us the second floor! A for me unique experience, it was so impressive that I immediately lost my way, as I always tend to do within cities and larger houses, after having turned the first corner; outside I do not lose my sense of direction as long as the sky is not completely overcast. But now I lost it even sooner than usual, and I started to make every error possible; where the NE bedroom was, who had slept there and where the eldest son, William Edwin Hamilton, had been born; things I usually know.* Having showed the rooms, Peter Gallagher kindly brought us to the gate, about which William Edwin wrote in his Peeps that when he was thirteen, thus in 1847, the “stone wall of the Observatory demesne [...] was pierced with an iron wicket gate,” and in 1831 Hamilton had written, when he was in England, “I must go out now while it is fine, and take a walk among these beautiful grounds, which however, after all, I do not prefer to the fields near the Observatory. Whenever I see a very gently swelling distant hill, with trees on its top, I imagine it is the Observatory, and I look for the little iron gate, and sometimes fancy that I see it too, for a moment.”

* Back home I remembered again: William Edwin, who was born on 10 May 1834, had started his Peeps with the sentence, “A squealing but healthy baby, embryo of the present writer, blinked its sore eyes for the first time in the north-east upper bedroom of the Dunsink Astronomical Observatory.” The second mentioning of these bedrooms had to do with Lady Hamilton’s ‘long absences’ from the Observatory, which during the 20th century were used to ‘prove’ that she was unfit to be a good wife for Hamilton. I wrote in my AVM, “When the Hamiltons arrived at the Observatory in April [1833], according to Hankins two huge pillars “were being erected right through the house to support the new equatorial in the dome.” Wayman adds: “Adaptations to the dome structure and its fixtures went on. For on 18 November [1833] WRH wrote that Lord Adare was expected at Dunsink in a day or two, where he would occupy the NE bedroom, above the dining room, instead of the SE bedroom.” And although it is not clear if construction work was going on all through the year, even as late as December 1834 Hamilton wrote to uncle James that he thought about staying at Bayly Farm for another month, “the Observatory being still unfinished.”” Next to thus knowing that in Hamilton’s time the dining room was the northeast room on the ground floor, imagine taking care of a small child in such circumstances, at those times when many children died young, the house had to be warmed by hearth fires, and all the light in the evening and early morning came from candles; what would we have done in their place.

It is, btw, also certain that the drawing-room was downstairs, and that it was not his library. Yet as far as I know, there is no consensus about where Hamilton’s library was, or his study. It is likely these were two names for the same room; Hamilton called the room where he worked his library, and it would obviously be very inconvenient not to have his books at hand when working. Next to some hints which suggest the library was downstairs but which are no proofs in themselves, there is one good reason to assume that also the library was indeed downstairs; in 1853 it was ‘cleared out’ for a “sort of official dinner” for the Examiners for Bishop Law’s Mathematical Premium. It is unlikely that these ‘eminent guests’ would have dined upstairs where the bedrooms were, thus more or less preventing the rest of the family to go to bed before the dinner was over. It is also not known why the dinner was not held in the dining-room; perhaps it just was also more convenient for the family to be able to dine there, they may have had guests themselves.

Very happy and grateful that Peter Gallagher had shown us the second floor, we hurried to try to catch up with the Walk. Having walked across the sloping field* to the Royal Canal, at some time we were very uncertain where to go. And just at that moment there was someone from the organization who showed us the way! Walking along the canal, we felt great disappointment when we saw the bridge and no one was there. But then we realised it was a bridge too early, and hurrying on, to our great relief the group had assembled at Broom Bridge, and Tony O’Farrell’s talk had not begun yet.

* On the 23rd of April 1858 Hamilton organized a “Feast of the Poets” at the Observatory, which was amongst others attended by Aubrey de Vere and Speranza, Mrs. Wilde. The feast was described by Graves, “The well-beloved garden and the nearly-equally loved sloping field below the little iron gate, were the scenes of merry and serious converse, of recitations and readings, including both original effusions and poems by great masters of the lyre.”

All this explains why, on the photo Fiacre allowed us to take, I look as if I had come running.

Fiacre Ó Cairbre and I at Broom Bridge, 16 Oct 2024.

Having catched our breaths a little, we listened to Tony O’Farrell who gave his yearly performance, as always standing on the bridge. In this 01m 16s short video, he speaks about Hamilton’s dynamics, and the connection of his faith with it, a connection also Isaac Newton had with his work. And in this one, 00m 35s, O’Farrell speaks about the discovery of the quaternions; it is only the beginning because unfortunately, then our power run out. We therefore also do not have footage of how he, having finished, jumped off the bridge!

Tony O’Farrell speeching on Broom Bridge, 16 Oct 2024.

Returning to Dublin, we went back to Dominick street for a last time, to look at the plaque, and we drank a beer in the same pub at the end of Upper Dominick street as we had done in 2015, when we had not been able to find the house. The owner did not remember it any more, but he was the one who had sent us to the King’s Inns, where, in one of the very thick books we saw that afternoon, I had seen for the first time a trace of Graves’ blue pencil! And where we had found very valuable information about Hamilton’s father, Archibald Hamilton, which I still have to incorporate in an article about him; the most difficult thing I still have to do. Yet it has to be preceded by information about Hamilton’s extended family, showing his privileged background.

Hamilton certainly enjoyed the circumstances in which he could do what De Morgan stated that Robert Murphy could not do, but what is necessary to do mathematics at such high levels, “give his undivided attention to researches which, above all others, demand both peace of mind and undisturbed leisure.” And at the same time that is not enough; Hamilton was also prepared to work very hard, and spend a good part of his life in his study. After Hamilton’s death, De Morgan wrote to Lady Hamilton, “His memory will be very bright and very lasting. I trust that care will be taken to illustrate the singular variety of his attainments and the fertility of his mind. His publications give no more than a glimpse of what he was out of mathematics. Nor must it be left unrecorded how truly good he was as a man and a member of Society.”

The plaques which now exist for him, the plaque composition at Broombridge, the old one which now is at Dunsink, and the new one in Dominick Street, were well-deserved. What a day this had been.

Utrecht, 25 March 2024

—

A father, a mother and a little son in Juvigny-sur-Loison : Hamilton’s French ancestors

From 1748 until 1749 a little boy lived in Juvigny-sur-Loison. His name was Henry Thomas Guinin, and the reason to mention him here is that he was the very early deceased little brother of Mary Anne Guinin, Hamilton’s maternal grandmother, which means that Henry Thomas was Hamilton’s granduncle. This connection was made following a memorandum by Hamilton about a family connection between his friend and former pupil Lord Adare, later Earl of Dunraven, and himself. It was based on information supplied to him by “Old Mr. Webber”, and given by Graves in a footnote of his biography. An ancestor linking Hamilton to Lord Adare is missing, and because Graves called him a sixth cousin, perhaps even two. But the relation between Mr. Webber and Hamilton, via Mary Anne Guinin, appeared to be completely traceable.

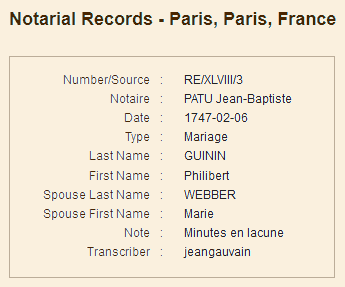

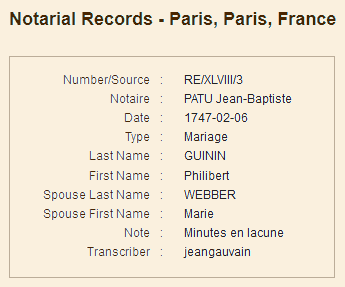

After having found, last year, the transcription of the marriage record of Marie Webber and Philibert Guinin, I started a search on Geneanet, and readily found a family tree of a certain Philibert Guinin, whose data seemed to meet all requirements. I contacted the owner of the page, Valérie Perrin Launay, to show her the Parish marriage record and ask her about Philibert Guinin, and she kindly sent me screenshots of documents. With the information on her page, now knowing what to look for, I made an account on Geneanet. Slowly getting used to the ‘record-French’, it was possible to gain a view on the Guinin family of Juvigny-sur-Loison in the first half of the eighteenth century. From the original records it is clear that Philibert Guinin was actually called ‘Philbert’, after his godfather Philbert Gilles, and Mary Webber seems to have been called ‘Marie’ only in France.

The scans of the handwritten records were published on the Archives of the Meuse department, where the Guinins lived. The records mentioned hereafter were undersigned by Jean Clément, who from 1717 to 1750 was curé of the Abbaye Sainte-Scholastique* in Juvigny, which immediately confirms that the Guinin family was Roman Catholic. The Benedictine abbey, which was founded in 870, does not exist any more; the contemporary church of Saint Denis was built in 1774, therefore after the Guinins had left. Yet it is remarkable how much of Juvigny-sur-Loison, then called Juvigny-des-Dames, in the late 18th century drawing of the abbey, including the then new church, is still recognisable.

* St. Scholastica (480-547) is believed to have been a twin sister of St. Benedict. Relics are at the abbey of Monte Cassino, Italy, or at Fleury abbey in Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire, France, and at the church of St. Denis in Juvigny-sur-Loison, France. The relics of St. Scholastica had been placed in the Abbaye St. Scholastique, but three years after the beginning of the French revolution, in 1792, they were brought to the church of St. Denis, which had been consecrated in 1774. The abbey was demolished in 1794. The relics are processed three-yearly during the feast of St. Scholastica in February.

The Guinin family

Philbert Guinin was born 21 September 1723. His baptism record reads,

Baptisme. L’an 1723 le 21e du mois de 7bre a esté baptisé par Mre Jean Clement curé de Juvigny le fils de Jean Guinin Buraliste de ce lieu, et d'Antoinette Blandin ses pere et mere maries ensemble et de cette paroisse, auquel on a imposé le nom de Philbert. Le parrain a esté Philbert Gilles, la marreinne Alexise Fourier qui ont signes.

Philbert Gille(s) Alexice Fourier J Clement, curé

Baptism. The year 1723 on the 21st of the month of September was baptized by M(essi)re Jean Clement parish priest of Juvigny the son of Jean Guinin Tobacconist of this place, and of Antoinette Blandin. His father and mother married together and of this parish, on him was imposed the name of Philbert. The godfather was Philbert Gilles, the godmother Alexise Fourier who have signed.

Philbert Gilles (ca 1697-1735), the godfather.

Alexice Fourier (ca 1696-1774), the godmother.

Philbert and Alexice had married in 1718.

In 1747 Philbert married Mary (Marie) Webber in Paris,

Unfortunately, the original record was not found online, nor the transcriber.

On 5 June 1748 Philbert and Marie had a little son, Henry Thomas Guinin. His baptism record reads,*

Baptisme. L’an 1748 le 5 Juin a esté baptisé par nous Jean Clement prestre curé Juvigny soussigné le fils de Philbert Guinin originaire de ce lieu, et demoiselle Marie Wibbert ses pere et mere mariés ensemble et residante en cette paroisse, de puis huit mois, environ au quel on a imposé le nom de Henry Tomas le parain a esté Henry Gilles jeune garçon la mareinne Barbe Françoise Scholastique Perceval qui ont signé, le pere de l’enfant, et nous dont acte.

P Guinin Henry Gilles Barbe Francoise Scholastique Perceval J Clement

Baptism. In the year 1748 on 5 June was baptized by us Jean Clement priest curate Juvigny undersigned the son of Philbert Guinin originally from this place, and young lady Marie Wibbert. His father and mother married together and residing in this parish since approximately eight months, on him was imposed the name of Henry Tomas. The godfather was Henry Gilles young boy the godmother Barbe Francoise Scholastic Perceval who signed, the father of the child, and we took note.

Philbert Guinin (1723-after 1754), the father.

Henry Gilles (b. 13 July 1730), the godfather. He was 17 when Henry Thomas was baptised, hence perhaps the striked-through ‘young boy’, or it should be translated as ‘bachelor’, yet that usually was written as ‘jeune fils’. Henry was a son of Philbert Gilles and Alexice Fourier, godparents of Philbert Guinin.

Barbe Francoise Scholastique Perceval (1730-1758), the godmother.

* Because there were small differences on the second pages of the two copies of the records, for comparison, the 1673-1761 version and the 1740-1749 version. In the 1673-1761 version the ‘Jeune Garçon’ was not erased.

But the next year Henry Thomas died. His burial record reads,

Mort. L’an 1749 le 12e 7bre a esté inhumé en ce cimetière Henry Thomas Guinin enfant aagé de 16 mois ou environ, et fils de Philbert Guinin et de Marie Wibert ses pere et mere abssent, cette enfant estoit originaire de ce lieu, et née avant l’abssence de ses pere et mere ont assisté a son enterement avec moy les soussigné, dont acte,

Pierre Lembinet J Guinin J Clement

Dead. In the year 1749 on the 12th of September was buried in this cemetery Henry Thomas Guinin child aged around 16 months, and son of Philbert Guinin and Marie Wibert his father and mother absent, this child was originally from this place, and born before the absence of his father and mother have attended his funeral with me the undersigned, duly noted,

Pierre Lembinet (1704-1767), whose surname was also written Lambinet, was a cousin of Philbert; his father Jean Guinin (1695-1773), a son of Alexandre Guinin (ca 1645-1729)* and Margueritte Vigneron (ca 1652-1712), had a sister, Jeanne Guinin (1678-1748). In 1702, she married Nicolas Lambinet (1677-1727), and Pierre was one of their sons.

J Guinin was Henry Thomas’ grandfather, Jean Guinin (1695-1773), father of Philbert. Jean did have a cousin who was a namesake, a son of Alexandre’s younger brother Toussaint Guinin (ca 1646-1710), but this Jean Guinin (1688-1761) lived in the neighbouring village Iré-le-Sec, and comparing their handwritings it is obvious this was the signature of Philbert’s father.** Both Pierre and Jean may also have been aides to the curé, Jean Clement, because their signature is found

more often in the records of that time.

*

The reason there are no exact baptism dates of most of the people born before circa 1650 is that such early records hardly exist. Most of the time, the year of birth is derived from the given age at death, but these dates were often uncertain, either called ‘ou environ’, or sometimes quite a few years off when compared with existing baptism records.

** Alexandre and Margueritte could not write, and marked their records, and it was remarkable to see how Jean’s handwriting improved over the years, and to see Philbert’s very neat handwriting.

At some time Philbert and Mary had left France indeed, because in 1754 Philbert Guinin was in Dublin where, as seen in the Irish records, he had become godfather to a boy called Thomas Genins, son of Thomas and Elizabeth Genins of the Roman Catholic parish of St. Andrew. The record not having been scanned yet, it is possible that the name Genins was a misread for Genin; the first name was not found in the Juvigny records, but Genin was very common throughout France, and was also found in the Juvigny records. It is therefore possible that also Thomas Genin(s) had come from France, and that Thomas and Philbert were somehow related, godparents were not chosen at random. It must be noted that the quite strict habit of calling the child after the godparent, as was nearly always found in the Juvigny records, was not kept up here, and perhaps not in Dublin in general. The Dublin records were not by far as extensive as the French records were.

Not any further record was found of the Guinins, until in 1779 their daughter Mary Anne Guinin married Robert Hutton in Dublin. In 1780 Mary Anne and Robert had a daughter Sarah, who in 1800 married Archibald Hamilton; they were the parents of Sir William Rowan Hamilton, born in 1805.

Contemplations

My French-English translations doubtless not always accurate, I do not understand what Henry Thomas’ burial record says; with his parents absent, Henry had the right to be interred there because they lived there when he was born? And what does it mean, that his parents were absent? Did they not attend the funeral, or had they left Juvigny altogether? But why would they leave without their son? Was he ill already, or too weak to survive such a journey which in those times was at least trying? And why did they leave, because Mary was Anglican? In France, protestants, or Calvinists, were prosecuted in waves, which only officially ended in 1787, and being Anglican probably did not help. Were the Guinins invited by family members in Ireland to come over? Or did they intend to emigrate to America, but they could not reach it and remained in Ireland instead?

If anyone has information, please contact me.

Henry was the name of the little boy’s godfather Henry Gilles. But his second name Thomas may have come from the Webber side; between 1650 and 1750 the name Thomas was regularly seen as a family name in Juvigny, but hardly as a given name. It was a ‘nom de guerre’ of Jean Genin (1663-1747), husband of Jeanne Guinin (1674-1756), great aunt of Philbert, yet is was not customary to give those names to children. More likely is that he was called after Mary’s brother Thomas Webber, who was born 1723, and therewith of the same age as Philbert Guinin. He married Letitia Irwin, and died in 1770.

On the Geni website it is suggested that Mary and Thomas were half-siblings; that Thomas was a son of Isabella, and Mary a daughter of Arabella. That may be erroneous; it is much more likely that Isabella, of whom not any data was given, and Arabella Wallis were the same person, making Mary and Thomas siblings, not half-siblings. In his biography of Hamilton, Graves made a similar error; he once called Hamilton’s friend Arabella Lawrence “Miss Isabella Lawrence.” Because it is very unlikely that Hamilton made that error, it must have been a reading error; when handwritings are not very clear, this is an easy mistake to make.

Six reasons to believe Philbert and Mary really were Hamilton’s great-grandparents

1. There is Hamilton’s memorandum, mentioned above, with the information of “Old Mr Webber” claiming a family relationship. This would be established through Mary Webber’s marriage to Philbert Guinin.

2. The very rare family name of Hamilton’s grandmother Mary Anne Guinin. That Mary Hutton of Fairfield (1792-1887) erroneously gave the name as ‘Marianne Guissand’ is very understandable; she most likely knew her as ‘Mari-anne’ Hutton.

3. Although on Geneanet, in France between 1700 and 1750, the name Marie Webber or Wibert, as was written in Henry’s burial record, is not too uncommon, the name of her husband is; even with name variants, there are only four archives results for Philbert Guinin, and they are all of the Philbert who was married to Marie Webber (Vuilbert/Wibbert/Wilbert); their marriage, the birth of Henry Thomas, and his burial.

4.

The second name of their son Henry Thomas was, even with name variants, not found as a given name in the Guinin family in the Meuse region between 1500 and 1750, and only six times in other French regions. But as mentioned, it was the name of one of Marie’s brothers.

5. The timeline is correct; the Guinins were not heard of again in France after the death of their little son Henry Thomas in 1749, and a Philbertus Guinin was appeared in the Dublin Roman Catholic church records in 1754.

6. Last but certainly not least, some time ago I contacted Scott Witham, a Hutton descendant who is active on Wikitree and on the Geni website. He confirmed that in family trees or records Arabella was sometimes called Isabella, which means that they were one and the same person, making Marie and Thomas Webber siblings indeed. He then wrote something which exactly fits in with the above findings. I had asked if one of Hamilton’s cousins, William Hamilton Willey, a son of his Uncle Willey, was called after him, and he answered, “My grandfather’s grandfather, William Hamilton Willey, was most certainly named after his cousin. I have a letter written to his son, John J. Willey by his cousin, the English Moravian Minister Robt. Baynes Willey, who claims that Mary Webber married a ‘M.Guinon, French, of Juneray Compagne,’ and he believed that they were married in Dublin. I have no idea what is meant by ‘Juneray Compagne,’ which reads like a mistake or mistranslation.” A Marie Webber marrying a Guinin of Juvigny is hardly just a coincidence, en although they married in Paris, in 1779 their daughter Mary Anne Guinin married Robert Hutton in Dublin; they would become Hamilton’s maternal grandparents.

Conclusion: although none of these arguments would have been a confirmation by itself, I believe that the combination does not leave room for doubt any more; Hamilton’s maternal great-grandparents were Philbert Guinin and Mary Webber.

Update 26 May 2024

Two days ago I received the final confirmation that this Philbert Guinin was indeed Hamilton’s great grandfather. It came in the form of a book I could borrow through Inter Library Loan, The Register of the Parish of St. Thomas, Dublin, 1750 to 1791, edited by Raymond Refausse, and published by the Representative Church Body Library. It is not open access, but fortunately, the index of surnames was published online, in which I found the Guinin name, yet without any further information. Having received the book I saw, to my happiness, on page 20, listing names of baptisms in 1756, after May, 9, “Bridget Lettitia, daughter of Philbert & Mary Guinin.” This is the definite piece of information I hoped for; Philbert Guinin and Mary Webber now lived in Dublin. It was a surprise to find that Hamilton’s grandmother Mary Anne Guinin had a sister Bridget, who thus was a great aunt of Hamilton; it is not known why they were not mentioned in Graves’ biography, although the idea that Graves tried to keep out people of other religous denominations again seems to apply.

On p. 7 of the Register it is explained that the parish of St Thomas “was created in 1749 by an act of the Irish parliament which divided the parish of St Mary into two distinct parts.” Although the records of the parish of St Mary are in the collective Irish church records, those of the parish of St Thomas are not, which explains the absence of Bridget’s baptism record. It was also not found where the name Bridget came from, perhaps she had a godmother called Bridget, but the Register does not give godparents. The name Lettitia was easy to recognise; as mentioned above, Mary Webber’s brother Thomas had married Letitia Irwin. Coincidentally, that same year, in Carlow, on 8 October 1756, Thomas and Letitia had a daughter, Mallabella. And around 1757 their son Daniel Webb Webber was born, who most likely was the ‘Old Mr Webber’ who had told Hamilton about his family relations with Lord Adare, with which this search had started.

The Register yielded another surprise, on p. 87, namely that Thomas Webber Esqr was buried on 6 May 1770, had been 47 when he died, and had as his address Palace Row, on the northwest of Rutland Square. Having been 47 in 1770 is in perfect accord with the statement that Thomas, Mary’s brother, was born in 1723. Remarkably, the Alumni Dublinenses states that Daniel Webb Webber was born in Sligo, and both the AD and the King’s Inns Admission Papers state that he was the only son of “Thomas, of Dublin.” The KI papers also show there was a second Daniel Webber, eldest son of “Thomas, late Capt. 4th Horse”, and either the information in the King’s Inns papers is incorrect, or the page describing Daniel Webb Webber’s father on the History of Parliament page merged the data of these two Daniels. It is possible that Mary’s brother Thomas was a captain though; in any case in 1769 and 1770 a Captain Thomas Webber was in the Dublin Directories, but not any more in 1771, signifying he was the Thomas Webber who died in 1770. Therefore, having had a child in Carlow, another in Sligo, where Letitia’s family lived, and Daniel having had his education in Portarlington, Thomas may have been travelling, as many people then had to do, but also had a house in Dublin as a ‘base’ address. That seems to be confirmed by the above mentioned data in the Register, the genealogical abstract of his prerogative record which mentions his widow, Letitia, and the records at the National Archives, all three mentioning that Thomas, who died intestate, had been a Dublin Esquire.

This all leads to some likely conclusions. First, that not only Philbert had relations in Dublin, but also Mary had; her brother Thomas and his wife Letitia very likely having had a house in or very near* St Thomas, the parish in which also Philbert and Mary’s daughter was baptised, it is possible that they lived in her brother’s house. Second, that it is possible that they left France because Mary was protestant and did not feel safe or at home in France; the fact that Philbert became godfather of a Roman Catholic boy, and two years later agreed with his daughter being baptised in the CoI, signifies that he felt at home in both denominations.

* Curiously, Palace Row, now Parnell Square North, then apparently was in St. Thomas parish, yet in 1830 it was in St. Mary. It was in any case very close to the church of St. Thomas, which between 1758 and 1762 was built at Marlborough Street.

What still is an enigma is why Philbert and Mary left their little boy in France; even though he was taken care of by family, it must have been a very difficult decision.

And it is unfortunate that in all these searches the birth year of Mary Anne Guinin, Hamilton’s maternal grandmother, was not found. She married in 1779, and if she married when she was around 25, she may have been born around 1754, six years after her little brother Henry, and two years before her sister Bridget. According to Graves, she died in March 1837, and would have been around 83 when she died. But neither of Philbert Guinin and Mary Webber, nor of Mary Anne Guinin and Robert Hutton, burial records were found.

Utrecht, 5 March 2024

—

Dublin Collinses (CoI)

In order to facilitate my ongoing searches for Hamilton’s family members, instead of making a lot of bookmarks I decided to make an overview of the sources I was using. Then it seemed a good idea to extend it with a complete list of all Dublin Directories and Almanacks between 1729 and 1840 I had found online, preferrably open access or at least free of charge;* the only source which appeared to be indispensable yet behind a paywall was FindmyPast. I was assisted by my sister, who helped with information from copies from her library, of volumes which are not available online. Because making the overview was quite labour-intensive I decided to place it online, hopefully more people will find it useful, and in that case I did not just do it for my own, one-time use.

* The Dublin Directory being the most important source for the whereabouts of Hamilton’s family members, special thanks are due to the librarians of McGill University; when I asked them about their copy of the Dublin Directory of 1807, which seemed to be the only one held in libraries, they immediately scanned the volume containing it, and uploaded it to the Internet Archive!

But then it was time to search for the last hitherto unknown family member in Graves’ family tree. Because “G. Whistler”, husband of Margaret Hamilton, the sister of Cousin Arthur, had been found so easily, I expected it would also be possible to find “J. Collins”, the husband of the other Margaret Hamilton, a sister of Hamilton’s grandfather William Hamilton. I did not know what hit me. No matter what I tried, and no matter how many more sources I used, having found many Collinses it appeared they used only a handful of first names, and in most cases it was impossible to decide whether or not two Collinses sharing a given name were the same person or not. To be able to recognise patterns I made a Collins overview,* again without much success. Now the best idea seemed to be to just place it online, hoping that there are people who can make some combinations and add some more relationships. Because there is a possibility that I did find the “J. Collins” I was looking for, but it is mainly based on the fact that he was the only Collins who married, in 1780 or somewhat earlier, a woman named Margaret.

* For the time being, the Dublin City council records have been taken offline. When they come online again, I will adjust the urls where necessary.

Added October 2025: I found that the information is still on the web: by filling in names in this database, the Dublin freemen from 1461 to 1491, and from 1564 to 1774, can be found. I will not update the urls in the Collins overview until the records come online again, but names and dates can be verified now.

The for my searches most important part of the Dublin Directories, the Merchants and Traders section, show that the Collinses were mostly weavers and merchants, but also other professions can be found, such as a gunsmith, a carpenter and a perfumer. Even an oculist turned dentist, but both professions only lasted for a year or so. And just as with the Huttons and the Hamiltons I wrote about earlier, some of them were very rich, and some influential. There were quite some freemen amongst them, and the overall feeling is that Francis Hamilton and Margaret Blood, Hamilton’s great-grandparents, would have had nothing against a marriage between one of the Collinses and their daughter Margaret Hamilton.

Yet until now, despite all my efforts, nothing was found of Francis Hamilton and Margaret Blood, except for what was written about Margaret after Francis had died already. The most logical assumption is that they did not marry in Dublin, and that, because not any church record was found, they moved to Dublin later. Even though it is therefore not known when Margaret Hamilton was born, some crude guesses can be made. What is known is that Hamilton’s grandmother Grace McFerrand, who in 1774 married the Dublin apothecary William Hamilton, was born in 1743. William was called the eldest son, but it is not known how many siblings he had, especially sisters who were often traceless in the records. The apparent second son, Francis Hamilton, the Dublin saddler, was born ca. 1753 or somewhat earlier, having become a freeman in 1777. Roger Hamilton, the youngest son, was an apprentice of William at the apothecary and took over after William died in 1783, he therefore was most likely born in the early 1750s.* If Margaret who married “J. Collins” was the eldest child, she was born around 1740, if she was the youngest, she was born around 1755. Then knowing that in 1821, when Hamilton wrote her a letter, Margaret lived in Aungier-street, it may not have been just a coincidence that in May 1831 a

Mrs Collins died at Aungier-street who was 75 years of age. If she was indeed the Margaret Hamilton sought after, she was born in 1755 or 1756.

* Hamilton’s mother-in-law, Anne Penelope Grueber, was born in 1762, and she married Henry Bayly in 1783. Helena Maria Bayly, who married Hamilton in 1833, was born in 1804, when her mother was 42, and she was not the youngest child. Therefore, assuming that also Margaret Blood, probably born ca 1710 and in any case before 1714, still had children in her forties, it is possible that the youngest child was indeed born in the 1750s.

This possibility, that Margaret was born in 1755 or 1756, would be a perfect match with the most promising possibility in the Dublin Directories. From records of freemen of the Weaver’s guild at Find my Past it is known that in 1775 a John Collins (hereafter called Jr.) became a freeman of the Weavers by Service to his father John Collins (Sr.), who was called a ‘free brother’.* Apprenticeships mostly took seven years, and most apprentices became freemen with 24, which means that John Jr. was born in or around 1753. And there is another coincidence; from the records at Dublincity.ie it appears that both in 1754 and in 1755 a John Collins became Freeman of the Weavers, one by Service and one by Grace Especial. Most often becoming a freeman, marrying and having a first child occurred within a few years’ period, either becoming free and then marrying, or the other way around. Therefore, one of these Johns may have been John’s father, but it is impossible to say which John was John Sr.. Still, because only one of them appeared in de Dublin Directories, the John who lived at 20, Liffey-street, it is possible that this is one and the same John, or that for instance the other John died early. The John of Liffey-street was in the Merchant and Traders' section from 1763 to 1780; once he was mentioned in the Dublin Directories as Warden and once as Master of his Guild, and for two periods of three years he was a member of the Dublin Common Council. Both times also Robert Hutton, the Tannery owner and Hamilton’s maternal great-grandfather, was in the Common Council, and immediatly after John Collins’ second period, in 1780, William Hamilton the apothecary, brother of Margaret and Hamilton’s grandfather, was elected in the Common Council. It seems safe to assume that these people moved in the same circles and that many of them knew each other well,** making it perfectly feasible that Margaret married John Sr.’s son.

* I do not know why John Jr. did not become Freeman by Birth, but in my searches I now and then did encounter a similar situation. There was somewhat more variation in freedom than I had expected beforehand.

If the John Collins who became a freeman in 1775 and therefore was born around 1750 was indeed a son of the John Collins of Liffey-street, this John Collins Sr. likely married and had children some years before becoming a freeman, which could point to the John Collins who became free by special grace. In or shortly before 1780 John Collins Jr. married a Margaret, and they had a son John in 1781, of whom a baptism record exists. If this Margaret was indeed the sister of William, Francis and Roger, she had her son when she was about 25, a regular age then to marry and start having children. In 1775, when he became a freeman, John Jr. lived or worked at the Coombe while from the baptism record of their son John it is known that in 1781 he was a Broad-weaver at Crooked staff, which is now Ardee-street. That is again perfectly possible; the Coombe and Crooked-staff almost formed an intersection with Pimlico and John-street, and John Jr. thus was working around the corner. Therefore, unless someone knows something more, for now I will assume that Margaret Hamilton married John Collins, son of John of Liffey-street and broad-weaver at Crooked-staff, had at least one child, also called John, and lived at the Coombe before she, or they, moved to Aungier-street.

The data in my Collins overview also contained a surprise which is worth noticing, even though it may not have had anything to do with Hamilton’s family. In April 1751, Samuel Collins married Rachael Darragh. They apparently had eight children; five sons and three daughters, of whom a son and a daughter may have died early. Why so much is known about them is that for more than twenty years they were in the Merchants and Traders section of the Dublin Directories, and both Samuel and Rachael made a will, of which Betham made abstracts.

In 1766 Samuel died; he had become a Freeman of the Weavers in 1748, by Grace Especial, and had been a Silk-and Ribband weaver at 32, Nicholas-street. Rachael took over the business and apparently, she managed very well, which was different from many women in those days. In 1776 she moved the business to 14, Bride-street, and after her death in February 1782 her eldest son, John, in 1779 having worked with her as Haberdasher and Manufacturer in Bride-street, and in 1781 having become a Freeman by Birth, began a business for himself at 79, Pill-lane, while her fourth son, William, took over the business at Bride-street. But only from newspapers it appeared how well she did. From Samuel, she had inherited 1500 pounds, then a large amount, yet through advertisements in October 1782 her Stock was sold, which give a glimpse of her life. She apparently had had her business in her “late Dwelling house”, which contained “a great Variety of Silk Handkerchiefs, flowered, striped, and plain Ribands, Modes, Persians, sewing Silks, Silk on Bobbins, &c. &c. Also three narrow Riband Engines, Tacklings, &c. likewise Engines for stamping and rolling Ribands, with a Number of Articles too numerous to insert,” and in similar advertisements also an Engine for Stamping Ribbons, Dutch Bobbin and Needles, together with Articles in the Haberdashery Way were mentioned. Indeed an impressive stock, and a nice insight into what it entailed to be a Silk- and Ribband Weaver.

Utrecht, 27 October 2023

—

Hamiltons and Huttons

Everything I am doing at the moment is in preparation of an article in which I want to show that Hamilton was not sent to Trim because of the financial circumstances of his parents, but because of his very early recognised, very out-of-the-ordinary intelligence. The first time I started to feel that writing such an article in a convincing way would perhaps be possible was when I was writing my Arabella Lawrence and Coleridge unpublication, and found the enormous Hutton family. It created an image of Hamilton’s youth which in Graves’ biography is not recognisable, and can only be seen after first giving much attention to the most minute details, and then reading the biography within the context of its time. And now, as always writing and correcting several unpublications at the same time, I suddenly was triggered by a remark made by Hamilton when he was seventeen, and still living in Trim. It was about a poem he had written, and showed a strong sense of kindred spiritness with the family of ‘Cousin Arthur’, as he is called in Graves’ biography. Arthur Hamilton was actually a cousin of Hamilton’s father Archibald, and I was surprised because I had not thought about him as even having had family apart from Archibald and uncle James and their families; in the biography Arthur comes across as a very nice person who doubtless had many friends, and as a father figure for the Hamilton siblings after the deaths of their parents, but not as having been surrounded by family of his own.

One of the steps towards the planned article was to show that the image of young Hamilton arising from Graves’ biography as a lonely, perhaps even socially naive, country boy is completely incorrect, as appeared after I had found the Hutton family and their enormous networks and, what should not be forgotten, uncle James’s circle of acquaintances which included the Edgeworths, the Disneys who then lived at Summerhill house, and the family of aunt Elizabeth, the Vicars and the LaTouches. I now also wanted to find as much as I could about Cousin Arthur’s Hamilton family, curious about who they were, and what their influence might have been on young Hamilton.

The only persons mentioned in Graves’ family tree are Arthur’s father Francis, and his sister Margaret, who according to Graves married a certain ‘G. Whistler’. That name being very uncommon, he soon appeared to have been Gabriel Whistler, and searching for him I readily stumbled on the Assembly rolls of Dublin in the Calendars of ancient records of Dublin which are available online at the Internet Archive (1447-1831), on the Gentleman[’s] and Citizen’s Almanacks, and Wilson’s Dublin Directories, later incorporated in the Treble Almanack, at the Internet Archive (1733-1743), Oireachtas Library (1771-1785), and HathiTrust (1808-1840s). In all collections years are missing, and some lonely volumes turn up elsewhere, but together they give a rather good overview for the years needed for my search after family members of Hamilton. I also decided to make an account on FamilySearch. I had long doubted making an account because I want everyone to be always able to immediately check what I claim, but it is free of charge and I really wanted to be thorough.* It soon appeared that, for now, the ancestors of Hamilton’s grandfather William Hamilton are impossible to find, but that his Hutton ancestors already lived in Dublin in 1662, and that he had a cousin four times removed, John Hutton, a Dublin Innholder who died in 1708. At the time Hamilton was born the Hutton family in Dublin was enormous already, and together with the fruitless searches for the Hamiltons, the search for which Huttons were, and were not, members of Hamilton’s family, became a very time consuming task.

But what I did find was again quite surprising, and together with Hamilton’s unexpected involvement with his enormous extended Hutton family, these finds now nullify the last parts of the general view on Hamilton as a lonely orphan with hardly any family to rely on except for his Uncle James, the country schoolmaster, and Cousin Arthur, the barrister who had managed to become something in society. Next to Hamilton’s father Archibald Hamilton having been an attorney at the King’s Inns and for instance law-agent to the Benchers, and cousin-in-law once removed Gabriel Whistler, solicitor in chancery, attorney and law-agent to the City, the overviews show many Dublin political careers.

On the Hutton side, Hamilton’s great-grandfather, the tannery owner Robert Hutton (ca.1720-1779), most likely his brother, George Hutton, and Robert’s sons Henry and Daniel, were with great regularity wardens of their guilds, sometimes master, and often members of the Dublin common council,* and on the Hamilton side the same holds for Hamilton’s great-uncle, the saddler Francis Hamilton (ca 1754-1830), and his son John, Arthur’s brother, of whom I had never heard before. Their political careers culminated in Robert Hutton becoming a very regular member of the common council, and becoming, for instance, one of the auditors of the Dublin city accounts in 1768, Henry Hutton becoming sheriff in 1793, alderman in 1796, and lord mayor in 1803, Francis Hamilton praying to be excused from becoming high-sheriff in 1805 and becoming sheriffs-peer and alderman in 1806, and his son-in-law Gabriel Whistler becoming sub-sheriff in 1802.

* To become a master or warden of a guild, one had to be a freeman of the guild. To become a member of the common council, one had to be a freeman of the city. For the difference between these two freedoms, see for instance this extract from the Third report on fictitious votes, 1837, part of the British Parliamentary papers.

Contrary to Graves’ unintentional image of a rather secluded young Hamilton because of his focus on members of the peerage, academics and the clergy, and greatly enhanced by Hankins in his 1980 biography because of a few errors he made, and his small suggestion of poverty which became part of the Hamiton stories, Hamilton grew up surrounded by family members at the top of Dublin society. The families were more than a distant coach-maker, however well-known John Hutton was, and an early deceased “eminent apothecary,” as Graves mentioned that Archibald Hamilton called his father William without proof.

And, as always, it was as what could be expected; having had the career Hamilton had, he must have had the best start possible. Many very intelligent people do not reach the realm of pure science in the way Hamilton did, and that was made possible by his large family who took care of troubles before they could slow their precious nephew down, as can be recognised, in hindsight, in small remarks Graves made in his biography. How marvellous uncle James, aunt Sydney and aunt Elizabeth were, they did not raise Hamilton alone. Which also explains, in hindsight, how Hamilton could very easily make friends, feel strong bonds with close friends and family, had very extended networks, and felt at home with a very broad spectrum of different people.

Utrecht, 7 June 2023

—

Hamilton’s elusive sister, Archianna Hamilton

The elusiveness of the youngest Hamilton sibling, Archianna (1815-1860), has its roots in the fact, as Hankins remarked in his 1980 biography of Hamilton, that “there is little mention of her in the family correspondence” [p. 12]. Yet Hankins then assumed that “she lived in Dublin until her death in 1860,” and subsequently concluded that “she must have lived a very quiet and retired life to be so inconspicuous in the mass of letters that Hamilton left behind.” Even when it appeared not very easy to find where Archianna lived between 1818 and 1860, and Hankins did not have the benefit of searching Graves’ biography digitally, that does not seem to have been the most logical assumption, nor conclusion. It is, moreover, embedded in Hankins’ staccato description of the early youths of the Hamilton sisters, taking up only one page [12] of his biography, but containing a number of mistakes about elementary facts given in Graves’ Victorian conceiled but factually nearly correct first chapters. This is the more unfortunate because Hankins’ other chapters, about Hamilton’s mathematics, religion, politics and philosophy, taking up four-fifth of the biography, were very reliable, leading his readers to also assume the correctness of the one-fifth part about Hamilton’s private life.

But it is remarkable that at times Graves even seems to have forgotten about Archianna. While Grace was regularly in Trim, according to Graves, in Spring 1818, a year after their mother Sarah’s sudden death in May 1817, William’s sisters Eliza and Sydney went to live with their maternal relatives in Ballinderry, the Moravian Willey family. Graves does not mention Archianna who then was only two years old, yet it rather appears to be an omission than some difficult arrangement with multiple homes for the sisters, as can be deduced from the following small remarks, made in January and October 1825.

In January 1825, in a letter written from Dublin to his uncle James in Trim, William explicitly mentioned that “Grace, Eliza, and Sydney had been at Kilmore,” the house near Clontarf of their great-uncle John Hutton, and were now with him at the house of ‘Cousin Arthur’. Visiting each other was now easy for the siblings, because William lived with Cousin Arthur in Dublin while attending college, and the sisters were enrolled in the school of the Misses Hincks, also in Dublin.* Archianna, who then was only nine years old, not being mentioned by her brother, there can be hardly any doubt that she was not in Dublin. It is logical to assume that she was still at school in Ballinderry, because the Moravians were used to not only teaching boys but also girls, and aunt Susan Willey was, as can be seen below, “a teacher in the Ballinderry ladies’s school” from 1817 until 1826.

* The ‘boarding and day school’ at 47 North Great George’s-street was run by two sisters, Bithia and Frances Hincks, who were related by marriage to the Hamiltons. In January 1825 Frances Hincks died but the school was not closed. From newspaper advertisements, it can be seen that Bithia Hincks continued the school, from 1828 together with Mademoiselle De Marval. In June 1834 Bithia had to retire for reasons of health, the school closed and the house was offered for sale by her cousin once removed Daniel Hutton, a brother of Hamilton’s grandfather Robert Hutton. In January 1835 a school was opened at the same address by someone else.

On 14 October 1825, William wrote a letter to Grace from Trim, and it can be assumed that the three sisters still were at the school in Dublin. Apparently, William had heard that Archianna would join them to celebrate Halloween in the house of Cousin Arthur, and wrote, “How pleasant it will be to meet all together again, after the anxiety of an October Examination, and after being so long separated! Archianna, too, will be with us this time, and add not a little to our enjoyment. I am afraid we are too old and sensible to care much for the nuts and apples - even burning nuts - and I do not know whether at Ballinderry such customs exist.” It is not certain whom William included in the “we,” but Grace was twenty-three then, William was twenty, Eliza eighteen, and Sydney fourteen or fifteen. The sisters having been living in Dublin, the remark about Ballinderry most likely referred to Archianna who then just had turned ten, and might still like burning nuts, if celebrating Halloween in this way was also a Moravian custom. Such remarks, combined with a lack of remarks about Archianna having lived elsewhere, make it seem safe to assume that Archianna had gone to Ballinderry with Eliza and Sydney, and that Graves simply forgot to mention her.

Showing that Hankins was incorrect when he assumed that Archianna had lived such a retired life appears to be closely connected to showing that she was the sister who Hamilton called a “Calvinist,” whom Hankins had assumed to have been “Sydney (and probably also Eliza)” [p. 230]. The assumption that Sydney was the sister Hamilton alluded to, was derived from a letter he wrote to a friend in 1859, “I [have] a very dear sister living, whom I very much respect as well as love, and who is a devoted Calvinist; being also - notwithstanding, as I might almost be tempted to say - but really I ought not to say it - an extremely pious and practical Christian.” Because in 1859 of the Hamilton sisters only Sydney and Archianna were still alive, one of them had to be the ‘devoted Calvinist’. But Hamilton also mentioned that his Calvinist sister had been a friend of William Henry Krause, which means that showing that it was Archianna would also mean showing that she did not live so “inconspicuously” that she hardly even made it into her brother’s papers, because in that case such a friendship would have been impossible.

Therefore trying to find some proof that Archianna was the ‘Calvinist’ sister, I decided to search the British newspapers again, and to my amazement I found Archianna’s death announcements. Having been born in 1815, she died in Dublin, on 16 February 1860 at 23 North Portland Street, the house (with a yard) which was rented by her sister Sydney, which is in accordance with Graves, who had written that she had died in February 1860, “when she was staying with her sister Sydney in Dublin.” Announcements were placed in papers in Dublin, Belfast, Cork and Limerick, and it is noteworthy that in the advertisements Archianna was called the “fifth daughter” because that means that the text was provided by people close to her, perhaps by her surviving siblings, William and Sydney. Archianna had indeed been the fifth daughter, because the fourth daughter was Sarah Susanna, who was born in 1812, and died in 1817, only a few months before also her mother died. But there was nothing to indicate the denomination Archianna belonged to, or where she was buried. It is possible she was buried at Mount Jerome because she is mentioned on the head stone of Hamilton’s grave, but she is not mentioned in the Mount Jerome records.

Also searching again for the online Dublin church records of the Hamiltons of Dominick street, hoping to find some patterns, the only baptism record appeared to be that of Archibald (1778) (Graves gave a convincing argument that Archibald was born in 1778 instead of 1779); there is nothing of Sarah and the children. In case of Sarah, that might be explained by the fact that contrary to Archibald, she most likely was not born within the parish of St. Mary, perhaps not even in Dublin, and she may not have been baptised in the Church of Ireland. For the eldest son called William it is explained by the fact that before he could be baptised, he died at Jervis street, where Archibald and Sarah may have lived with Archibald’s widowed mother Grace. It is most likely that, like Hamilton, the other children were baptised in the ‘dissenter’ Church of Ireland congregation of Benjamin Mathias in Dorset street, yielding two possibilities; either these baptism records have not been digitally processed yet, or they did not survive.

All extant burial records, of William (eldest brother, 1801), Sarah (daughter, 1817), Sarah (mother, 1817), Archibald (father, 1819), Grace (1846), and Eliza (1851), and are from the parish of St. Mary. Missing are the burial records of both sons called Archibald, William Rowan, Sydney and Archianna. One of Archianna’s little brothers was buried in Trim, and because there is a burial record for the eldest William, this brother must have been one of the two children called Archibald. He died before his cousin Kate but nothing further is known; Hamilton’s remark, made in 1822, about Kate having been buried “by the side of her little brother and mine,” does not say anything about whether or not he had known his little brother. Of the other son Archibald nothing was found. Of William Rowan, Sydney and Archianna it is certain that they not die in the parish of St. Mary; Hamilton died in 1865 at Dunsink Observatory which is in the parish of Castleknock, yet only his civil record was found, which just states that he died in Dublin North; died in Auckland, New Zealand, and was buried there at an Anglican cemetery, but that may not be a sufficient proof that she still was a member of the Anglican Church; Archianna died in North Portland Street, which is in the parish of St. George. Unfortunately, no further clues were found in the records, which means that for now there is nothing special about Archianna’s missing records.

Still not being able to show that Archianna was the Calvinist sister, there does seem to be an option which would make more sense than the assumption that Archianna lived an inconspicuous life; namely that she did not live in or even near Dublin. Because she was so very young when she went to live with the Willeys it is possible that, much more than her sisters did, she saw uncle John and aunt Susan as her parents. In favour of that option is one tiny detail which is not in Graves, but it was given by Hankins [1980, pp. 52-53]. In 1827, when Hamilton was appointed Andrews professor of astronomy and was going to move into Dunsink Observatory, aunt Susan wrote to both Hamilton and Sydney that, in Hankins’ words, “since he now had a home for them it was desireable that [his sisters] go to it.”

But then Grace and Eliza moved in with their brother, and Sydney a year later, yet Archianna never lived at the observatory. In 1827 Sydney had been in Rhodens, working as an assistant in the school of Mrs. Swanwick, most likely one of the many Swanwick relatives of the Hamiltons and the Huttons. At some time Archianna was travelling with her, but apparently she was not living with her. Sydney came to the observatory in 1828, but next to Hamilton mentioning that, according to Hankins, “Archianna will not for many years be ready” [to assist with the regular star observations], there was also no indication that Archianna should be taken in anyway because aunt Susan did not want to take care of her any more. It can easily be assumed that Archianna, who was thirteen now, was still at school in Ballinderry. And when five years later Hamilton married, the sisters left the observatory as was customary then. Even the servants left [Hankins 1980, p. 119] but also that was customary, to allow the new head of the household to choose her own household staff. Archianna was eighteen then, and she could not join her siblings at the observatory any more. Yet it is not certain that she did not move to Dublin then, and perhaps did disappear from sight.

Still, there is one last strangeness in Graves’ biography, and that is the near exclusion of Hamilton’s dissenter and protestant family members. It is possible that for Graves it simply was much more easy to access the Anglican records than the various protestant ones, but a feeling remains that he was uncomfortable with showing the subject of his biography within the mix of Anglicans and protestants, academics and non-academics he grew up in; the Hamiltons as Anglicans, the Huttons as both protestants and Anglicans, and both families having academic and non-academic members. Only once Graves showed something of his feelings of disdain about the protestants around Hamilton, when he wrote about Hamilton’s father Archibald, “A letter exists written by him to the Rev. Mr. [John] Willey, on the 10th of September, 1817, which manifests a largeness of view in religion scarcely to have been expected from a member of the Bethesda congregation, which then and long afterwards was noted for Calvinistic tenets of an extreme character.” If in that light the elusiveness of especially Hamilton’s maternal grandparents and of Archianna is considered, it might indicate that indeed Archianna was the Calvinist.

Concluding, it is a more likely scenario that Archianna indeed did not live in Dublin, but that she stayed with her uncle and aunt until they died, as many spinster daughters did. Women earned much less than men, and many elderly had to be taken care of, making it a profitable solution for both parties. From the time of their marriage in 1817 until 1826 the Willeys lived in Ballinderry Co. Antrim, and that is where Archianna came to live with them in 1818. Then they went to Cootehill Co. Cavan. In 1844 uncle John retired to Glenavy Co. Antrim, and they moved to Gracehill Co. Antrim in 1845, where uncle John died in 1847. Three years after her husband’s death aunt Susan went to Lurgan in Co. Armagh, and in 1857 to Woolford Halse in England. When in 1858 aunt Susan died, Archianna was forty-three, and she may have come to Dublin, to move in with her only living sister Sydney, perhaps having been happy that Sydney lived not too far from the Moravian church in Kevin Street. Archianna died in Sydney’s home in 1860. Where she was buried is not known, neither why and by whom it was decided to add her name on her brother’s gravestone. But it is good that her name is prominently there; she has been overlooked too often already.

Utrecht, 20 March 2023

—

Hamilton’s elusive grandparents, Robert Hutton and Mary Ann Guinin

Having found the importance in Hamilton’s life of his maternal relatives, the Hutton family, every now and then I made a futile attempt to find more about Hamilton’s elusive maternal grandparents, Robert Hutton and Mary Ann Guinin, whose marriage record was so easy to find. But when I lately made an inquiry about Hamilton’s youngest sister Archianna Priscilla Hannah (1815-1860), I received a very unexpected answer, which led to finding the wedding date and place of Mary Ann Guinin’s parents.

I had been happy to find the burial records of three of the four Hamilton sisters, and combining them with both Graves’ family tree and newspaper announcements nearly all their birth and death days, and their addresses are known. Grace (4 October 1802 - 13 June 1846), lived at 15 Upper Dominick street and died with 43. Eliza Mary (4 April 1807 - 14 May 1851) lived in Dorset Street and died with 44; until now I had not known where they lived in Dublin. Of Sydney Margaret (1810 / 1811 - 3 March 1889), who died with 78, there is a biographical sketch, and another one going with a photo of her gravestone. She emigrated to Nicaragua in 1862, and went to New Zealand in 1874, where she became a matron in the Auckland Asylum. She died “at the residence of Mrs Robertson, top of Hobson Street,” and was buried at the cemetery which now is called the George Maxwell Memorial Cemetery. Different from her sisters, a photo of her exists.